Read the full article about William Wilberforce here.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive these emails in your inbox.

On June 19, 1865, a Union general proclaimed that slaves in Texas were free. The anniversary of that day, known as “Juneteenth,” is now a federal holiday commemorating the abolition of slavery in the United States. It was also a significant milestone in the global movement towards universal emancipation.

While we don’t know exactly when slavery began, it appeared in virtually every civilization, including in Sumer, ancient Greece and Rome, medieval Europe, India, China, the Middle East, pre-colonial Africa, and the pre-Columbian Americas. However, in the 18th century, a strong abolitionist movement began to form in Great Britain and beyond. Public opinion started to shift against slavery while industrialization made it increasingly economically obsolete. International pressure for abolition mounted, first from the British Empire and later from international bodies like the League of Nations. Today, slavery is officially outlawed in every country.

Unfortunately, slavery has not yet been eliminated. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), there are 28 million slaves in the world today, or 50 million if you include forced marriages. These are heart-wrenching numbers, but it’s important to note that the ILO uses a very broad definition of slavery, which includes people compelled to work because their employer is withholding their wages or because they have no viable alternative. It cannot, therefore, be compared to the brutal chattel slavery common in pre-modern societies.

Eradicating this modern slavery will require alleviating the deprivation that allows people to be exploited. That means the final end of slavery will likely arrive only after absolute poverty disappears. However, we shouldn’t forget how far humanity has come. Thanks to centuries of progress, we no longer need to fight bloody wars or overturn broadly held norms to end slavery. The moral battle has been won, and that is worth celebrating.

Malcolm Cochran, Digital Communications Manager

Culture & Tolerance:

Energy & Environment:

- Apple Supplier TDK Claims Solid-State Battery Breakthrough

- The British Birds Saved from the Brink of Extinction

- One of World’s Rarest Cats No Longer Endangered

- California Startup Creates Key Electric Vehicle Battery Material from Methane

- Solar Is Going to Be Huge

- Conservation: Rare Caribbean Wildlife Species Saved from Extinction

- Plastic-Choked Rivers in Ecuador Are Being Cleared with Conveyor Belts

- The Untapped Potential of Geothermal Energy

Food & Hunger:

Health & Demographics:

- AI Outperforms Radiologists in Detecting Prostate Cancer on MRI

- GMO Mosquitoes Released in Djibouti to Fight Malaria

- New Blood Test May Detect Parkinson’s Years before Onset

- OpenAI Expands Healthcare Push with Color Health’s Cancer Copilot

- How Cancer Vaccines Could Keep Tumors from Coming Back

- ‘Space Hairdryer’ Regenerates Heart Tissue in Study

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Could Be Treated with a Malaria Drug

- Gilead’s Twice-Yearly Shot to Prevent HIV Succeeds in Late-Stage Trial

Science & Technology:

- Anthropic Releases ‘Most Intelligent’ AI Model in Rivalry with OpenAI

- DeepMind Creates AI Model That Can Add Sound to Silent Videos

- Waymo Says Its Driverless Cars Are 200 Percent Safer Than You

- Joby Says FAA Authorizes In-House Software for Air Taxi Service

- Mosquito-Fighting Drone Takes Flight in Broward

- India’s Farmers Are Now Getting Their News from AI Anchors

- Walmart Plans to Launch Digital Shelf Tags in 2,300 Stores

Tweets:

Blog Post | Politics & Freedom

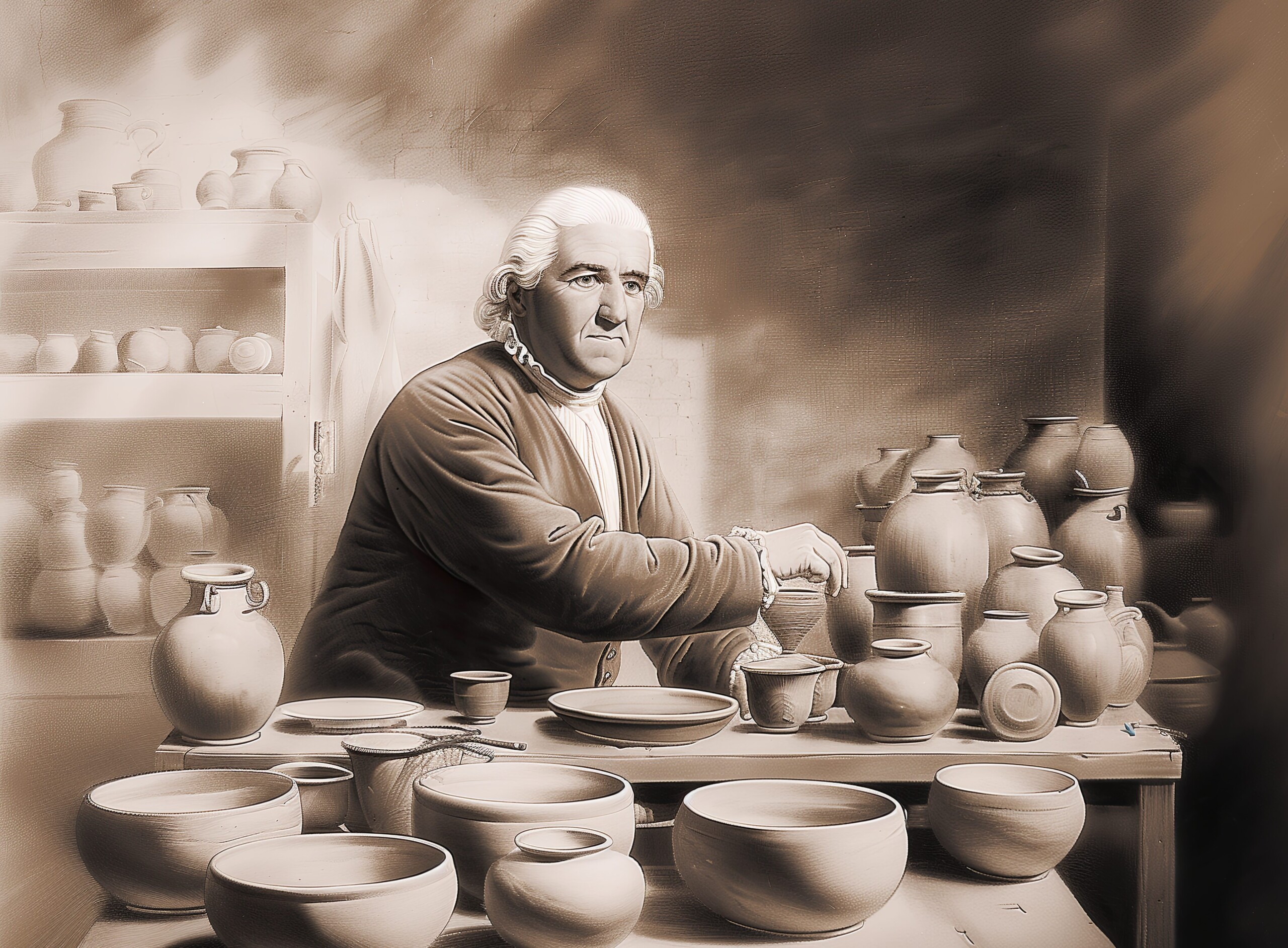

Underrated Industrialist, Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood was an entrepreneur, abolitionist, inventor, and in many respects the first modern philanthropist.

Summary: Josiah Wedgwood challenged the prevailing perspective on entrepreneurship, rising from humble beginnings to become an esteemed industrialists and advocates of Enlightenment ideals. Wedgwood’s story exemplifies the transformative power of entrepreneurship, philanthropy, and innovation, reshaping not only the economy but also societal perceptions of wealth and social responsibility.

This article was published at Libertarianism.org on 12/18/2023.

We use and encounter the word “entrepreneur” constantly in our daily lives. Entrepreneurs are an indispensable part of the modern economy, but for much of the Western world’s history, aristocratic elites looked down on merchants as crass money-makers. A long tradition stretching back to antiquity enforced the aristocratic view of property ownership and agriculture as the only honorable ways of making money. But in the 18th century, things started to change dramatically.

At the forefront of change was Josiah Wedgwood, a man born the child of a potter, who ended his life as an esteemed industrialist, a trendsetter for English society, and an advocate of Enlightenment ideals. He is also one of first examples of the entrepreneurial philanthropist in the modern sense, using his profits to build schools, homes, and improve the working conditions of his employees. Most famously, he was a staunch advocate for the abolition of slavery.

Wedgwood’s Upbringing

Josiah Wedgwood was born on the 12th of July 1730 in Burslem, Staffordshire. He was the eleventh child of Thomas and Mary Wedgwood. Wedgwood’s family, while not poor, was not particularly rich either.

Wedgwood’s father and his father’s father had both been potters. According to all conventional wisdom, Wedgwood would follow in his ancestors’ footsteps and earn a similarly modest living. Though there were many potters in his hometown of Staffordshire, potters only sold their wares locally. To sell to London was rare; to sell abroad was unheard of. Staffordshire was not the cosmopolitan center of the United Kingdom. By the end of Wedgwood’s life, this all radically changed.

From a young age, Wedgwood showed great promise as a potter, but at the age of nine he contracted smallpox, permanently weakening his knee, meaning he could not use the foot pedal on a potter’s wheel. But Wedgwood took this tragedy in stride despite his young age. While healing, he used his spare time to read, research, and most importantly, experiment. Instead of making the same pots his family had always crafted, he dedicated himself to innovating.

Combining Science and Faith

After his father’s death, Wedgwood’s mother took charge of educating her son imparting to him a deep appreciation for curiosity. Wedgwood came from a family of English dissenters, Protestants who broke off from the English state-supported Anglican church to start their own religious establishments. Specifically, Wedgwood and his family were Unitarian: they emphasized the importance of humans using reason to interpret scripture. Unlike many of their contemporaries, Unitarians did not see science and religion as conflicting ways of viewing the world but complementary. Because of this attitude, Unitarians were often found defending freedom of speech and conscience as indispensable rights for political and religious life.

Where Unitarians split most noticeably from the established Anglican church was their view of Original Sin. Growing up, Wedgwood was taught that the world could be made a better place through human effort. A modern observer views progress and making the world a better place as a common aspiration, however, few of our ancestors believed there was such a thing as consistent material or moral progress. It is easy to see why, given that belief system, most people were content to work the same job their father had using the same tools that had been used for hundreds if not thousands of years.

The Beginnings of a Business

At the age of 30, Wedgwood began his own business in Staffordshire at his Ivy House factory. Because of England’s vast colonial territories, tea and coffee were making their way to England in larger quantities. The emerging middle class began to frequent coffee and tea houses to converse with their peers, dramatically increasing the demand for pottery. Wedgwood observed an increased demand for pottery, but also an increased demand for beauty and style in everyday items.

In Wedgwood’s early days of business, elaborate designs were not popular; what was demanded was the pure simplicity of materials like porcelain. Porcelain, however, was in short supply and extremely fragile. To remedy this, Wedgwood began developing cream glaze that would give earthenware the appearance of porcelain with none of the downsides. After conducting over 5,000 painstaking tests, Wedgwood perfected what came to be known as creamware, something few of his competitors replicated.

Increasingly known for his high-quality products, Wedgwood was invited to participate in a competition with all the potteries of Staffordshire to provide a tea service or set for Queen Charlotte. Knowing this was a crucial opportunity, Wedgwood went all-in on creating a creamware set, even painstakingly using honey to help stick 22-karat gold to his pure white creamware. Wedgwood won the competition and was made the Queen’s potter. Wedgwood was light years ahead of his competition when it came to marketing and branding, and from this point onwards, all of the company’s paperwork and stationery boasted the royal association.

Wedgwood and the Consumer Experience

Wedgwood established showrooms in London to sell his wares. In the 18th century, most stores were cramped and dingy places. Wedgwood also pioneered a range of services we expect as standard today, including money-back guarantees, free delivery, illustrated catalogs, and even an early form of self-checkout. More than any of his contemporaries, Wedgwood focused on perfecting the retail experience. His showrooms were immediately popular, establishing his reputation throughout London, Bath, Liverpool, Dublin, and Westminster. Some showrooms were so popular they caused traffic jams with long-winding lines stretching through the street.

The Division of Labor and International Markets

The increasing demand led to Wedgwood being so successful he founded a new factory in 1769 named “Etruria” after the Etruscans of ancient Italy. Here Wedgwood dreamed of becoming “Vase Maker General to the Universe.” Despite being named after an ancient land, it was arguably at the time the most modern industrial space in the world. To minimize mistakes, Wedgwood broke down the process of making earthenware into a series of smaller tasks. Like the contemporaneous Adam Smith, Wedgwood observed that the division of labor dramatically increases productivity. As an employer, Wedgwood was an exemplar of humane business. Knowing the hot conditions of factories, he attempted to develop a form of air conditioning. He paid his employees well and provided cottages for his workers around Etruria.

With his modernizing practices, Wedgwood brought artistic perfection to an industrial scale. Though many of his popular products were initially purchased by the aristocracy, he eventually reduced the prices to appeal to an increasingly broader market. Wedgwood noticed that a high price was necessary to make the vases esteemed ornaments for palaces, but once aristocrats popularized his products, he would then reduce the price accordingly. Everyday people began to drink from mugs and decorate their homes with vases that for centuries had been exclusively owned by aristocrats.

Wedgwood had transformed Staffordshire from a town that nearly always sold their produce locally to a place that supplied goods for the whole nation. But Wedgwood saw the potential for further expansion abroad. Wedgwood began to ship to Europe but then rapidly expanded across the globe to places like Mexico, the United States, Turkey, and China. By the 1780s, Wedgwood was exporting most of his products abroad. Though during this period of his life business was booming, Wedgwood’s smallpox afflicted knee worsened, resulting in his leg being amputated without anesthetic and replaced with a wooden prosthetic. Seemingly unbothered, Wedgwood Christened the event “St. Amputation Day” and resumed work.

Business for a Good Cause

As Wedgwood shipped more goods abroad, he increasingly frequented London’s port, the largest slave-trading port in the world at the time. Wedgwood saw the whip-scarred bodies of enslaved people being shipped in from abroad. Wedgwood abhorred slavery, not only because it was immoral, but because for Wedgwood, it was not befitting of the national character and the esteem Britain ought to hold as a free nation. At its inception, in 1787 Wedgwood joined the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

He campaigned against slavery by using his craft to create mass-produced cameos of a black man in chains on his knees against a white background with an inscription beneath reading “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” Wedgwood gave away these medallions free of charge to abolitionist groups, even sending medallions to Benjamin Franklin, then to the president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Franklin praised his medallions, saying their effectiveness was equal to the best written works against slavery. Gentlemen had this image inlaid in their snuff boxes, and ladies wore it on bracelets and hairpins.

A friend of Wedgwood and fellow abolitionist wrote of Wedgwood’s medallions, “the taste for wearing them became general, and thus fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honorable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom.” Wedgwood saw how fashion could be a vehicle for political change. His medallions perfectly captured the message of the abolitionist cause, two hundred years before the advent of the t-shirt, today’s preferred method of displaying one’s political affections.

Wedgwood was not only a master craftsman, an industrialist, and an activist: he was also a scientist. In 1765, he joined the Lunar Society of Birmingham, a group of industrialists, scientists, and philosophers who met during the full moon because the light made the journey at night easier. Members included people such as Joseph Priestly and Matthew Bolton. In 1783, Wedgwood was elected to The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge by inventing the pyrometer, a device used to measure the high temperatures of kilns while firing pottery.

Death and Legacy

After a life dedicated to his work and the betterment of the world, Wedgwood passed away on the 3rd of January 1795 at the age of 64. The name Wedgwood became synonymous with excellence in pottery, and remains so today.

Throughout Western history, aristocrats, nobles, and other elites often peddled a narrative that prosperity was achieved through familial ties of property ownership and military prowess. People like Josiah Wedgwood challenged this narrative by showing a new path for the Enlightened industrialist and philanthropist. Instead of making his fortune from familial connections and war, Wedgwood showed the peaceful path to wealth by simply fulfilling consumers’ desires. His marketing practices were light years ahead of his time, and his penchant for building a distinct brand through advertising and high-quality goods was an unprecedentedly modern strategy at a time when the wealthy still wore powdered wigs.

Wedgwood used his wealth to benefit the world by treating his workers with dignity while advocating for humane causes like the abolition of slavery. Stories like Wedgwood’s counter the anti-capitalist narrative of the corrupting tendencies of private enterprise, showing how business can be humane, cosmopolitan, and most importantly, for Wedgwood, beautiful.

Imagine, if you will, the following scenario. It is 1723, and you are invited to dinner in a bucolic New England countryside, unspoiled by the ravages of the Industrial Revolution. There, you encounter a family of English settlers who left the Old World to start a new life in North America. The father, muscles bulging after a vigorous day of work on the farm, sits at the head of the table, reading from the Bible. His beautiful wife, dressed in rustic finery, is putting finishing touches on a pot of hearty stew. The son, a strapping lad of 17, has just returned from an invigorating horse ride, while the daughter, aged 12, is playing with her dolls. Aside from the antiquated gender roles, what’s there not to like?

As an idealized depiction of pre-industrial life, the setting is easily recognizable to anyone familiar with Romantic writing or films such as Gone with the Wind or the Lord of the Rings trilogy. As a description of reality, however, it is rubbish; balderdash; nonsense and humbug. More likely than not, the father is in agonizing and chronic pain from decades of hard labor. His wife’s lungs, destroyed by years of indoor pollution, make her cough blood. Soon, she will be dead. The daughter, the family being too poor to afford a dowry, will spend her life as a spinster, shunned by her peers. And the son, having recently visited a prostitute, is suffering from a mysterious ailment that will make him blind in five years and kill him before he is 30.

For most of human history, life was very difficult for most people. They lacked basic medicines and died relatively young. They had no painkillers, and people with ailments spent much of their lives in agonizing pain. Entire families lived in bug-infested dwellings that offered neither comfort nor privacy. They worked in the fields from sunrise to sunset, yet hunger and famines were common. Transportation was primitive, and most people never traveled beyond their native villages or nearest towns. Ignorance and illiteracy were rife. The “good old days” were, by and large, very bad for the great majority of humankind. Since then, humanity has made enormous progress—especially over the course of the last two centuries.

How much progress?

Life expectancy before the modern era, which is to say, the last 200 years or so, was between ages 25 and 30. Today, the global average is 73 years old. It is 78 in the United States and 85 in Hong Kong.

In the mid-18th century, 40 percent of children died before their 15th birthday in Sweden and 50 percent in Bavaria. That was not unusual. The average child mortality among hunter-gatherers was 49 percent. Today, global child mortality is 4 percent. It is 0.3 percent in the Nordic nations and Japan.

Most of the people who survived into adulthood lived on the equivalent of $2 per day—a permanent state of penury that lasted from the start of the agricultural revolution 10,000 years ago until the 1800s. Today, the global average is $35—adjusted for inflation. Put differently, the average inhabitant of the world is 18 times better off.

With rising incomes came a massive reduction in absolute poverty, which fell from 90 percent in the early 19th century to 40 percent in 1980 to less than 10 percent today. As scholars from the Brookings Institution put it, “Poverty reduction of this magnitude is unparalleled in history.”

Along with absolute poverty came hunger. Famines were once common, and the average food consumption in France did not reach 2,000 calories per person per day until the 1820s. Today, the global average is approaching 3,000 calories, and obesity is an increasing problem—even in sub-Saharan Africa.

Almost 90 percent of people worldwide in 1820 were illiterate. Today, over 90 percent of humanity is literate. As late as 1870, the total length of schooling at all levels of education for people between the ages of 24 and 65 was 0.5 years. Today, it is nine years.

These are the basics, but don’t forget other conveniences of modern life, such as antibiotics. President Calvin Coolidge’s son died from an infected blister, which he developed while playing tennis at the White House in 1924. Four years later, Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin. Or think of air conditioning, the arrival of which increased productivity and, therefore, standards of living in the American South and ensured that New Yorkers didn’t have to sleep on outside staircases during the summer to keep cool.

So far, I have chiefly focused only on material improvements. Technological change, which drives material progress forward, is cumulative. But the unprecedented prosperity that most people enjoy today isn’t the most remarkable aspect of modern life. That must be the gradual improvement in our treatment of one another and of the natural world around us—a fact that’s even more remarkable given that human nature is largely unchanging.

Let’s start with the most obvious. Slavery can be traced back to Sumer, a Middle Eastern civilization that flourished between 4,500 BC and 1,900 BC. Over the succeeding 4,000 years, every civilization at one point or another practiced chattel slavery. Today, it is banned in every country on Earth.

In ancient Greece and many other cultures, women were the property of men. They were deliberately kept confined and ignorant. And while it is true that the status of women ranged widely throughout history, it was only in 1893 New Zealand that women obtained the right to vote. Today, the only place where women have no vote is the Papal Election at the Vatican.

A similar story can be told about gays and lesbians. It is a myth that the equality, which gays and lesbians enjoy in the West today, is merely a return to a happy ancient past. The Greeks tolerated (and highly regulated) sexual encounters among men, but lesbianism (women being the property of men) was unacceptable. The same was true about relationships between adult males. In the end, all men were expected to marry and produce children for the military.

Similarly, it is a mistake to create a dichotomy between males and the rest. Most men in history never had political power. The United States was the first country on Earth where most free men could vote in the early 1800s. Prior to that, men formed the backbone of oppressed peasantry, whose job was to feed the aristocrats and die in their wars.

Strange though it may sound, given the Russian barbarism in Ukraine and Hamas’s in Israel, data suggests that humans are more peaceful than they used to be. Five hundred years ago, great powers were at war 100 percent of the time. Every springtime, armies moved, invaded the neighbor’s territory, and fought until wintertime. War was the norm. Today, it is peace. In fact, this year marks 70 years since the last war between great powers. No comparable period of peace exists in the historical record.

Homicides are also down. At the time of Leonardo Da Vinci, some 73 out of every 100,000 Italians could expect to be murdered in their lifetimes. Today, it is less than one. Something similar has happened in Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, Scandinavia, and many other places on Earth.

Human sacrifice, cannibalism, eunuchs, harems, dueling, foot-binding, heretic and witch burning, public torture and executions, infanticide, freak shows and laughing at the insane, as Harvard University’s Steven Pinker has documented, are all gone or linger only in the worst of the planet’s backwaters.

Finally, we are also more mindful of nonhumans. Lowering cats into a fire to make them scream was a popular spectacle in 16th century Paris. Ditto bearbaiting, a blood sport in which a chained bear and one or more dogs were forced to fight. Speaking of dogs, some were used as foot warmers while others were bred to run on a wheel, called a turnspit or dog wheel, to turn the meat in the kitchen. Whaling was also common.

Overwhelming evidence from across the academic disciplines clearly shows that we are richer, live longer, are better fed, and are better educated. Most of all, evidence shows that we are more humane. My point, therefore, is a simple one: this is the best time to be alive.

Lesson Plan: Dubrovnik (Public Health)

In this lesson, students will learn about the great public health achievements of medieval Dubrovnik, which developed early pandemic-response policies and facilitated great advancements in freedom for its inhabitants.

You can find a PDF of this lesson plan here.

Lesson Overview

Featured article: Centers of Progress, Pt. 37: Dubrovnik (Public Health) by Chelsea Follett

Dubrovnik is a beautiful walled city on the Dalmatian coast of Croatia. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Mediterranean. But did you know that it was also once home to one of the freest and most cosmopolitan societies in Europe and one of the first societies to implement comprehensive public health measures to contain disease?

Chelsea Follet writes, “Not only was the small city-state of the Republic of Ragusa at the forefront of freedom for its time, being one of the earliest countries to ban slavery, but the glittering merchant city on the sea was also the site of an early milestone in the history of public health: quarantine waiting periods, which were first implemented in 1377.”

Warm-up

Where is Dubrovnik? What is it like there? Watch this 5-minute video from Rick Steves to build background about this picturesque city.

When you’re done watching, with partners, in small groups, or as a whole class, respond to the following questions:

- In the 15th century, what were the mainstays of Dubrovnik’s economy?

- Steves mentions that the city walls were fortified about 500 years ago. Which world power threatened Dubrovnik during that time?

- Dubrovnik remained independent until the 1800s. Make an educated guess: Which European power took control over the city at that time?

- Which conflict affected Dubrovnik during the 1990s, resulting in significant damage to many buildings?

Questions for reading, writing, and discussion

Read the article, then answer the following questions:

- The Describe the political structure of the Republic of Ragusa during its period of independence from 1358 to 1808. Why was this type of governance unique for that period?

- What sociopolitical practice does Follett cite as important to maintaining the pool of eligible aristocrats charged with governing the city-state?

- The constitution of the Republic of Ragusa stipulated that the top government official had a term limit of just one month. What do you think were the likely social and political effects of that limit?

- The article discusses several manifestations of Dubrovnik’s economic ethos of capitalism and free trade. Describe three specific examples of these economic ideas from the article.

- The article also cites several ways that Dubrovnik promoted freedom and human rights. Explain three specific examples of these humanistic ideals mentioned in the article.

- What were some of the ways that Dubrovnik promoted public health prior to and during the Black Death? Name at least three.

- Dubrovnik is famous as the originator of a systematic quarantine policy for those possibly carrying infectious diseases. What is the etymology of the word “quarantine”? How is the meaning of that word specifically related to victims of the bubonic plague?

Extension Activity/Homework

Make a case study of your community.

Follett holds up Dubrovnik as a model. She uses detailed information to argue that peace, prosperity, and tolerance come about when there is respect for individual rights, the promotion of economic freedom, and limited government.

Create a Google Presentation or PowerPoint about your own community. Make a case for the dominant ethos of your hometown and explain why it has helped to grow your community. For this case study, conduct research and present information about:

- History: founding, important figures, growth over the years

- Population: age range, racial and ethnic groups, languages spoken, religions

- Economy: main sectors, number and types of jobs, big employers

- Institutions: government structure, schools and colleges, civil society (churches, clubs, nonprofits, etc.)

- Outlook: What does the future hold for your community?

Create at least 10 slides. Be creative. Find or take photos to supplement your writing. Think deeply about why your hometown has been successful. Does it have a strong tradition of public education? A tight-knit faith community? A strategic location near key economic resources? Make an argument about why it’s been a success.

Write about quarantine and isolation.

Over the centuries, the government of Dubrovnik instituted quarantine policies for all those entering the city from infected areas. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, billions of people around the world also went through a prolonged period during which they were isolated from friends and family. You were likely unable to see your loved ones for many months.

How did this period of isolation affect you? How did you change and/or grow as a person? What did you like about that time? What did you dislike?

In a short reflective piece—either a paragraph, poem, song, drawing, or another creative medium of your choice—describe your personal reaction to this period of prolonged isolation.