Today is the third instalment of a new series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled, The Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column gives a short overview of unsung heroes, who have made an extraordinary contribution to the wellbeing of humanity. You can find the 2nd part of this series here.

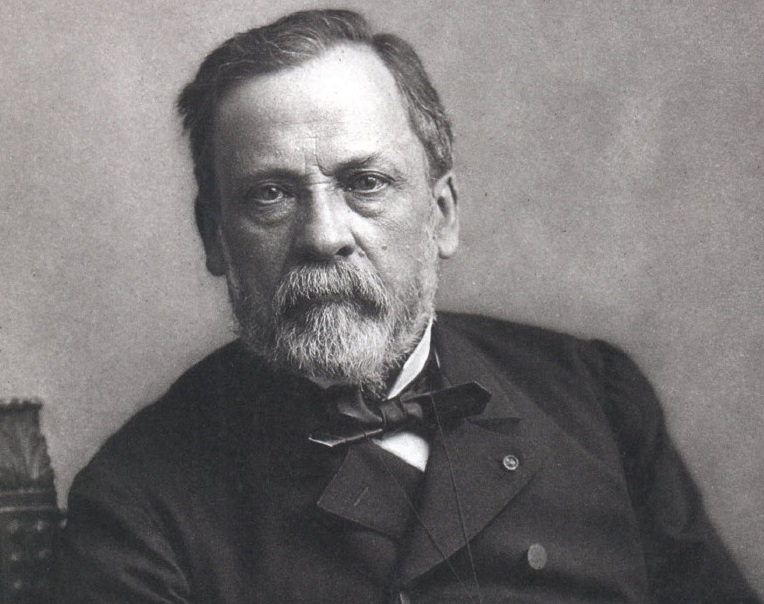

Our third Hero of Progress is Edward Jenner, an 18th century English physician who pioneered the smallpox vaccination – the world’s first vaccine.

Before it was eradicated in 1979, smallpox was one of humanity’s oldest and most devastating scourges. The virus, which can be traced back to pharaonic Egypt, is thought to have killed between 300 and 500 million people in the 20th century alone.

The “speckled monster,” as it was known in 18th century England, smallpox was highly contagious and left the victim’s body covered with abscesses that caused immense scarring. If the viral infection was strong enough, the immune system of the patient collapsed, and the person died.

The mortality rate for smallpox was between 20 and 60 percent, and of those lucky enough to survive, a third were left blind. Among infants, it was 80 percent.

Enter, Edward Jenner.

Born in Gloucestershire in 1749, Jenner was successfully inoculated against smallpox at the age of 8. Between the age of 14 to 21 he apprenticed for a county surgeon in Devon. In 1770, he enrolled as a pupil at St. George’s Hospital in London.

At the hospital Jenner had a variety of interests: he studied geology, conducted experiments on human blood, built and twice launched his own hydrogen balloons, and conducted a particularly lengthy study on the cuckoo bird.

In May 1796, Jenner turned his attention to smallpox. For many years Jenner had heard stories that dairymaids were immune to smallpox because they had already contracted cowpox – a mild disease from cows that resembles smallpox – when they were children.

Jenner found a young dairymaid by the name of Sarah Nelms who had recently been infected with cowpox from Blossom, a cow whose hide still hangs on the wall of St. George’s medical hospital. Jenner extracted pus from one of Nelms’ pustules and inserted it in an 8-year old boy named James Phipps – the son of Jenner’s gardener.

Phipps developed a mild fever, but no infection. Two months later, Jenner inoculated the boy with a fresh smallpox lesion and no disease developed. Jenner concluded that the experiment had been a success and he named the new procedure vaccination from the Latin wordvacca meaning cow.

The American physician Donald Hopkins has noted, “Jenner’s unique contribution was not that he inoculated a few persons with cowpox, but that he then proved that they were immune to smallpox.”

The success of Jenner’s discovery quickly spread around Europe. Napoleon, who was at war with Britain at the time, had all his troops vaccinated, awarded Jenner a medal, and even released two English prisoners at Jenner’s request. Napoleon is cited as having said he could not “refuse anything to one of the greatest benefactors of mankind.”

Jenner made no attempt to enrich himself through his discovery and he even built a small one-room hut in his garden, where he would vaccinate the poor free of charge – he called it the “Temple of Vaccinia.” Later in life he was appointed Physician Extraordinary to King George IV and was made mayor of Berkeley, Gloucestershire. He died on January 26th, 1823, aged 73.

In 1979, the World Health Organization officially declared smallpox an eradicated disease.

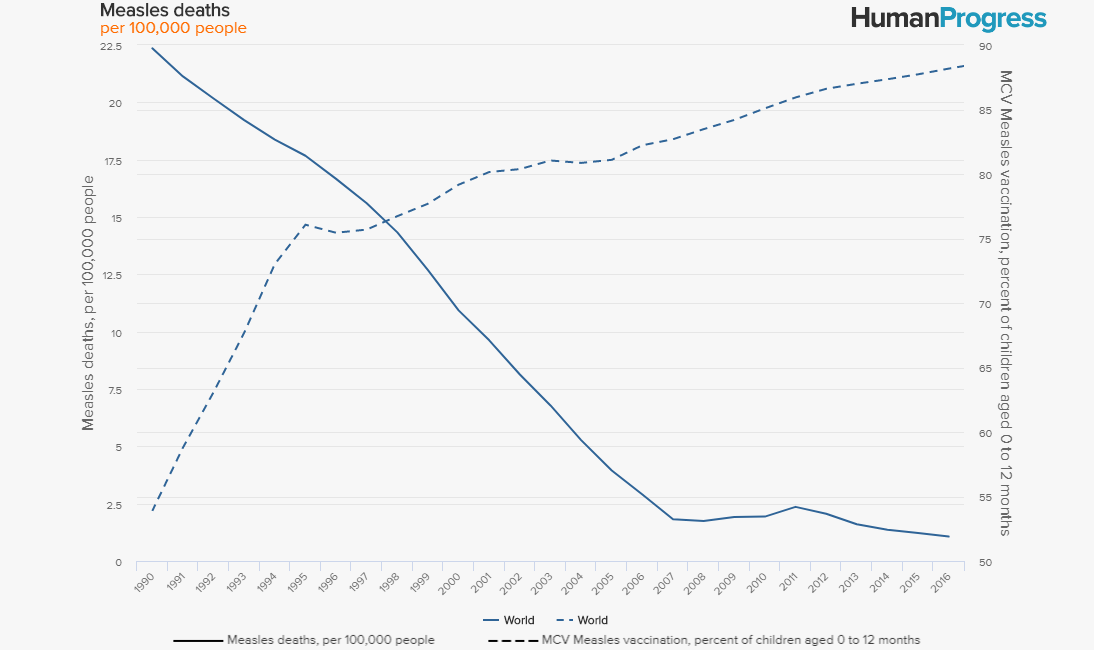

The smallpox vaccine laid the foundation for other discoveries in immunology and the amelioration of diseases such as measles (rubeola), influenza (the flu), tuberculosis, diphtheria, tetanus (lockjaw), pertussis (whooping cough), hepatitis A and B, polio, yellow fever and rotavirus.

Jenner’s work has saved untold millions of lives from a disease that has plagued humanity for millennia and it is for that reason that Edward Jenner is our third Hero of Progress.