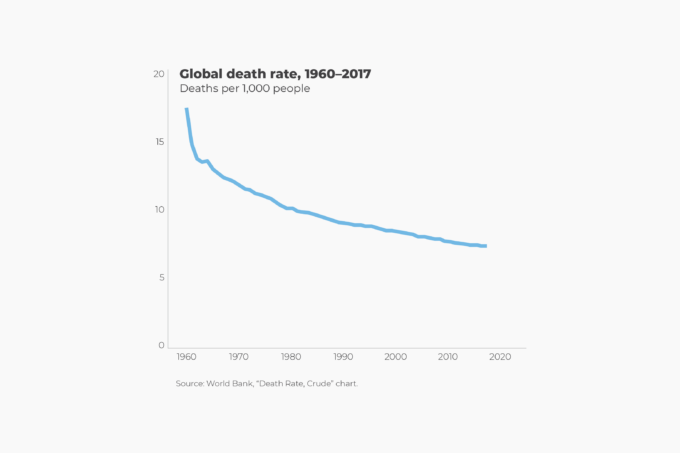

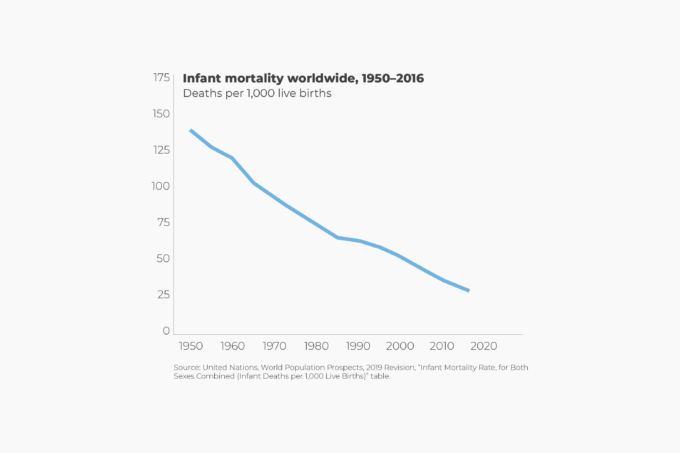

Before its eradication in 1979, smallpox was one of humanity’s oldest and most devastating scourges. The disease— which can be traced all the way back to pharaonic Egypt—was highly contagious. A 1775 French medical textbook, for example, estimated that 95 percent of the population contracted smallpox at some point during their lives. In the 20th century alone, the disease is thought to have killed between 300 million and 500 million people. The smallpox mortality rate among adults was between 20 percent and 60 percent. Among infants, it was 80 percent. Those figures partly explain why life expectancy remained between 25 and 30 years for so long.

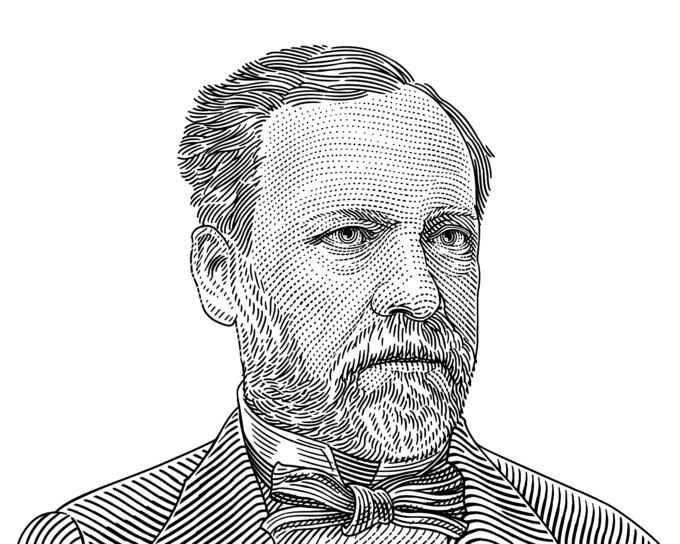

Edward Jenner, an English country doctor, noted that milkmaids never got smallpox. He hypothesized that milkmaids’ exposure to cowpox protected them from the much more deadly disease. In 1796, Jenner inserted cowpox pus from the hand of a milkmaid into the arm of a young boy. Jenner later exposed the boy to smallpox, but he remained healthy. Vacca is the Latin word for cow— hence the root of the English word “vaccination.”

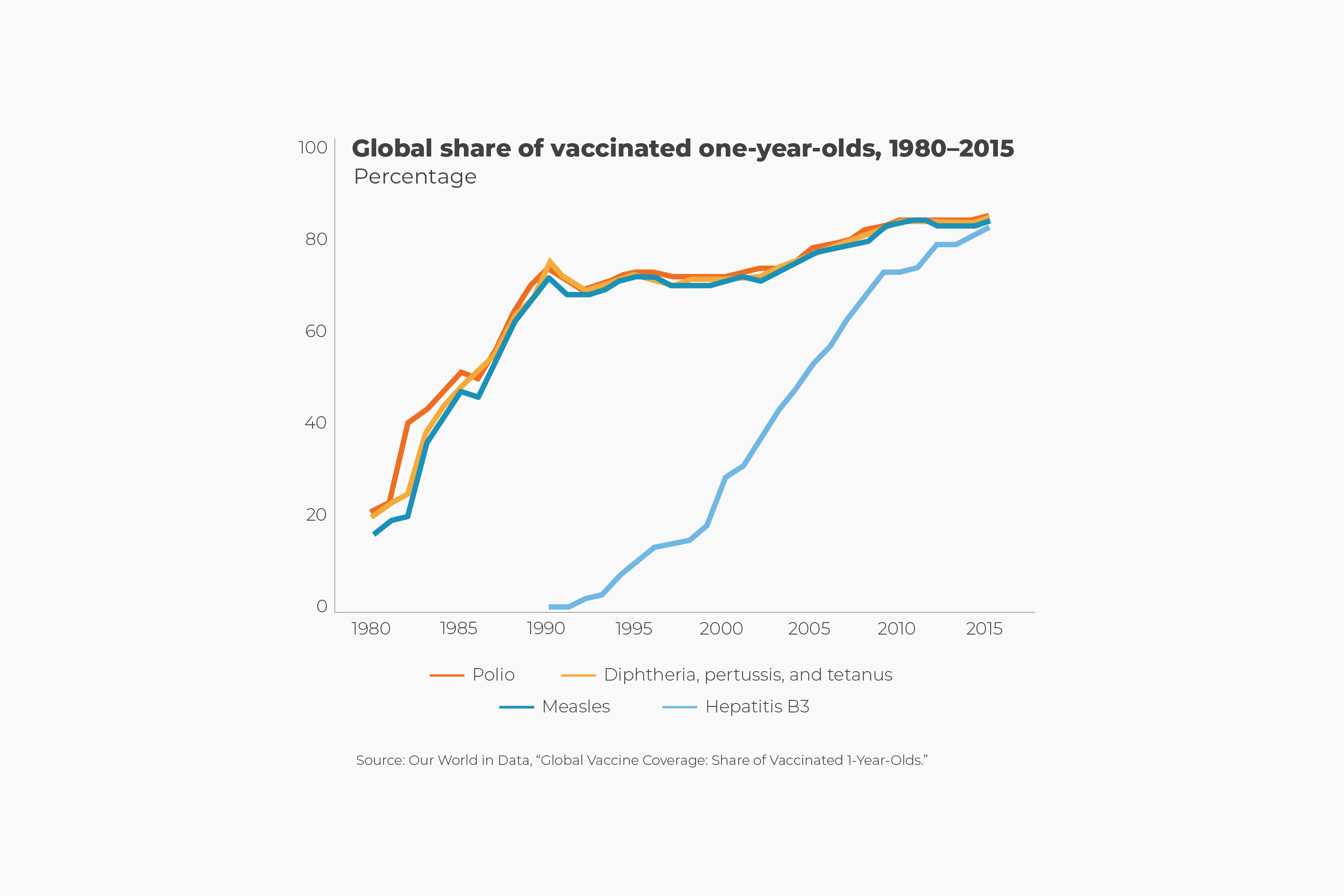

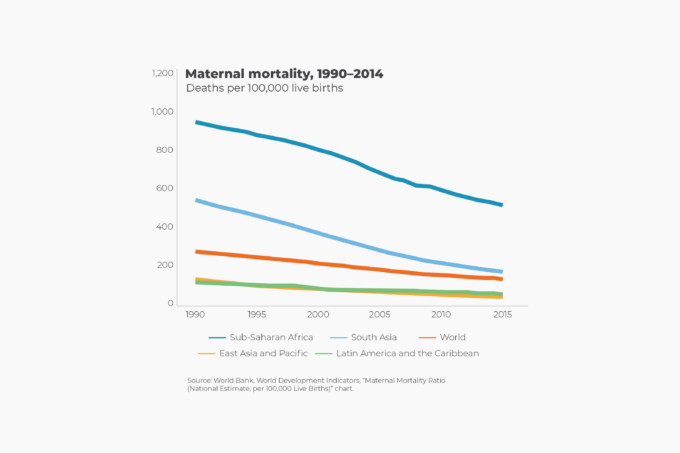

An organized effort by national governments, international organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector during the second half of the 20th century has brought a plethora of vaccines to the world’s most distant communities, thereby alleviating a great amount of human suffering. The World Health Organization estimates that vaccines prevented at least 10 million deaths between 2010 and 2015 alone. Many millions more lives were protected from illness.

As of 2018, global vaccination coverage remains at 85 percent, with no significant changes during the past few years. That said, an additional 1.5 million deaths could be avoided if global immunization coverage improves.