Summary: The US health care system often looks chaotic, unfair, and expensive, but it is the world’s most powerful engine of medical innovation. Transformative breakthroughs often occur because of the incentives built into this messy system. However dysfunctional it may appear, America’s health care system reliably produces discoveries that other countries benefit from. The very features that make the system frustrating are also what keep it at the cutting edge of saving and improving lives.

The US health care system is often criticized for being expensive, wasteful, and cruelly indifferent to the least fortunate among us. Analysts point out its high costs, the seeming irrationalities in the system, and the middlemen who appear to be getting rich while providing little value. Someone being denied coverage for a treatment they need hits us at an emotional level. While defenders of the US system focus on its off-the-charts levels of innovation, the availability bias ensures that what people remember most are the horror stories of medical bankruptcies and denied claims, not the silent, invisible gains of new treatments and technologies that only exist because of the incentives embedded in this messy system.

My decades-long struggle with psoriasis is one example of how new medical treatments can change people’s lives for the better. All critiques of the US health care system must acknowledge that it is charting more new paths in medicine than any other system.

When I was a little kid, due to a mild case of psoriasis, my scalp would flake and cause dandruff. As I grew older, at some point—I can’t even tell you what decade it was—I started to get large and noticeable red spots on my back and torso. Maybe five years ago, these blotches had migrated to my face. When it was a body problem, I didn’t really care about it, since I’m not an Instagram model. But now I had to take this seriously.

I was luckier than many others with psoriasis because my blotches didn’t itch. They were simply ugly, misshapen patches on my skin.

Unfortunately, I was always told that treating psoriasis on the face is extremely difficult. Although you can use strong steroid creams and ointments on the body, the skin on one’s face is too sensitive, and it can thin out over time. So I had to use weaker versions of the same medications, and for me, these barely had any effect at all. Since I had no other options, I resorted to using the creams they gave me for my body on my face, even though I was warned that those could do long-term damage. Even then, their effect was weak to nonexistent.

Earlier this year, I had the nagging suspicion that the doctors I was seeing were being too conservative and that there must be some other way to deal with the issue. Using Google, I found a nearby clinic, run by an MD, that had “aesthetics” in its name and that combined medical and nonmedical cosmetic services. My hunch was that an office that did not pay lip service to this arbitrary division between beauty and medicine would be willing to do things on the cutting edge of treatment. As you will see, this will turn out to be a story about the benefits of not only profit incentives in medicine but also the much-maligned practice of medical and pharmaceutical advertising.

On my first trip to the office, the doctor informed me that in the current year, psoriasis isn’t a problem anymore. He would simply administer a shot, and it would go away. Shocked, I asked why all the other doctors had kept this a secret from me. He laughed and said that he couldn’t say. The medicine was called Skyrizi. He would give me one shot in the stomach, another in four weeks, and then I would only need the shot every 12 weeks as a maintenance dose. No side effects, problem solved.

I went home, did some research, and discovered that this was real. So I came back and received the first shot. Initially, the doctor said that since my case of psoriasis was mild, he would give me a daily pill. I replied that part of the appeal of the shot over the ointments was that I was busy with a successful career and three small children, and I didn’t want to waste time with an additional responsibility as part of my daily routine. The doctor said this was fine, even though he often recommended the pills if possible because some people are afraid of needles. I assured him this would not be an issue.

He then pulled out the specially designed single-use pen and gave me the injection.

I was told that this was a sample and that I only needed to go through my insurance to get preapproval for future doses. I didn’t feel anything with the first shot, and went home after getting it.

I worried that my insurance provider might not want to pay for this treatment. It seemed new and expensive. Soon after the first appointment, I received a call from a Skyrizi representative. Let’s call her Emily. She was reaching out to tell me all about the medication, answer any questions I might have had, and, if need be, go to war with the insurance company on my behalf to get it. She’d even come to my house and show me how to inject the medication myself the first time I received it. All of this was free of charge, which seemed quite strange. A person with anti-market biases might have been turned off by this practice, but I was open to the idea that our interests were aligned.

As I was worried that I might run into insurance difficulties, we had a conversation that went along the following lines:

Me: And how much would the medicine cost if the insurance company didn’t want to pay for it?

Emily: Around $20,000 per dose.

Me: What?!

Emily: Oh, but don’t worry about it! We’re going to get this taken care of for you.

At this point, I thought it was strange that the doctor had already given me a sample of something that supposedly cost $20,000. This wasn’t exactly a spoonful of ice cream. Even if the treatment worked, it was a bit out of my price range. I even wondered if the doctor’s office would call and demand that I reimburse them if the insurance company decided not to cover the medicine. I felt comfortable with Emily, but that seemed like a question too stupid to ask. Everything she said communicated a calm confidence that everything would work out fine. She projected seasoned expertise and clearly had experience living in the strange universe of the US health care system.

Four weeks later, the insurance approval was still in bureaucratic limbo. I called the doctor’s office and asked what we should do now that it was time for the second dose. Should I still come in for my appointment? The girl at the desk put me on hold and went to check something. She returned and said, “Don’t worry, we have another sample in the fridge.”

By now, this pharmaceutical company, through the doctor’s office, had given me $40,000 worth of treatment for no payment and my own personal concierge. Around the four-to-six-week mark, I realized the medicine was working. My psoriasis was fading away everywhere—my face, back, stomach, neck, and scalp—and without a single noticeable side effect.

Now I was determined to keep the supply flowing. To obtain this medicine, it turned out, I couldn’t go to a normal pharmacy. I needed to call one in a different part of the state, and it would then mail me the medication. The pharmacy eventually told me on the phone that my insurance was covering the treatment and that my copay would be a grand total of $4,000 per dose. “OK,” I thought, “I might actually be able to pay this, but it would still be a burden.” Before I expressed my shock, the pharmacist interrupted—I might be eligible to receive assistance, she said, if I call this other phone number.

So I did, and the woman on the line this time informed me that I had been approved for their payment plan. My new copay was zero. The pharmacy mailed me the first dose, and Emily came over on Labor Day to show me how to do the injection myself for the first time, 12 weeks after the second sample dose. I don’t think I needed her, but she was always nice and eager to help, so I didn’t mind meeting her at least once. She even brought me an imitation injection pen, which we practiced with before doing the real thing. I was allowed to keep it as a souvenir, along with a pile of informational booklets for reference and numbers to call in case I had any questions.

As soon as the doctor decided I needed Skyrizi, an entire machine sprang into motion to ensure that I would get my medication conveniently and without paying anything. On paper, this medicine should have cost about $100,000 in my first year, and even after my copay, around $20,000. But these numbers had no connection to any price I would ever be responsible for.

They were all fake. Apparently, since the marginal costs of making a dose of the medication were low, the pharmaceutical company was willing to go above and beyond to make sure I received the treatment. For reasons I don’t understand, it had to be done in this strange and roundabout way. Hopefully, a health care expert can one day explain it to me.

Psoriasis is caused by an individual’s immune system going into overdrive. Our bodies use chemical signals to fight off infections. One of those signaling molecules, interleukin-23 (IL-23), is sometimes too active, and the body attacks its own skin. Made by AbbVie Inc., a Chicago-based company, Skyrizi is a type of drug called a monoclonal antibody, which is a lab-made protein designed to stick to IL-23 and block it from sending those harmful signals. By targeting solely this one pathway, Skyrizi reduces the redness, scaling, and inflammation seen in psoriasis while lowering the risk of broader side effects that come with older medicines that suppress the entire immune system. In the United States, the drug was approved for plaque psoriasis only in 2019, and it was approved for psoriatic arthritis and Crohn’s disease in 2022.

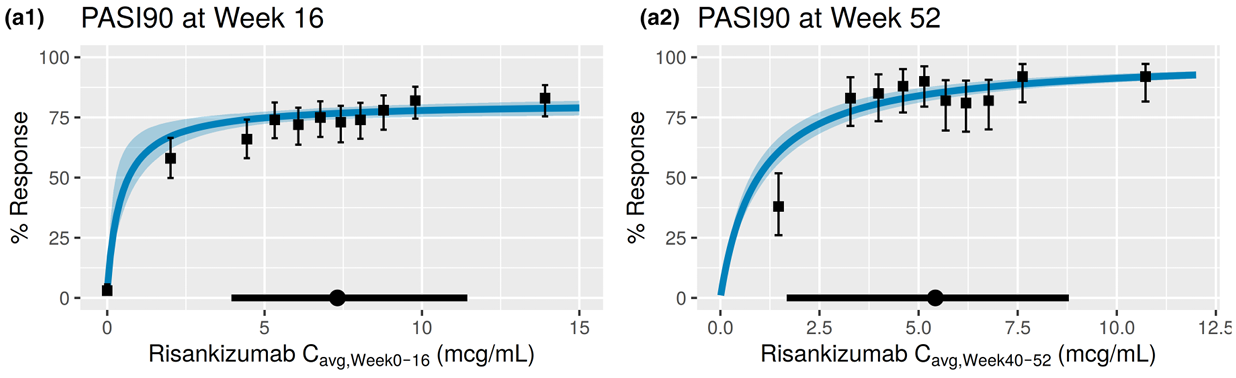

The figure below shows the percentage of people reaching a PASI (psoriasis area and severity index) 90 level, which means 90 percent clearance of psoriasis symptoms, after taking risankizumab, which is the name of the active ingredient in Skyrizi. The x-axis on each plot shows the dosage received by patients. As you can see, the effect plateaus quite early, with around 70 percent of people achieving the almost complete elimination of symptoms within 16 weeks, a number that increases to about 80 percent at the end of 52 weeks. It really is a miracle cure. It just ends psoriasis for the vast majority of people who take it (to be clear, no pharmaceutical company or interest paid me to write this article).

Figure 1

This entire process looks irrational. A cost of $20,000 per dose seems absurd. While I didn’t directly pay for the medication, that number must mean something, and one would think that the pharmaceutical companies charging such seemingly exorbitant prices must be screwing over the consumer in some way. The system of free samples, a pharmaceutical rep personally lobbying me to take the drug, and the large copay that magically disappeared with a single phone call gave the whole process a shady quality. Even a supporter of free markets in health care probably wouldn’t think things should work like this.

In other developed countries, price controls are much stricter, and central planning is more direct, rather than relying on a patchwork of imaginary prices. Sometimes these prices may be completely covered by insurance, and other times they are either unaffordable or offset by seemingly arbitrary discounts.

Yet, as silly and haphazard as this system looks, it is the innovative engine of the world. The United States carries out the largest share of global research and development in the life sciences. US-based researchers are estimated to generate around 80 percent of the most important breakthroughs in medical, biochemical, and biotechnological fields. Even when companies that make breakthroughs are not in the United States, they are motivated to invest in innovation because they can make more money here than anywhere else.

A 2018 analysis found that US consumers account for 64–78 percent of global pharmaceutical profits, illustrating how US spending and pricing structures subsidize innovation that benefits patients globally. Collectively, these figures underscore the centrality of the United States in shaping medical advancements through both high-volume research activity and breakthrough discoveries. Freedom to advertise new drugs and treatments is another part of the US health care system that is extremely rare. Without the clinic’s slick advertising and the Skyrizi brand ambassador holding my hand through the entire complicated process, I may have never gotten the medicine.

What if we had adopted single-payer health care a generation ago? I would’ve probably received a lifetime supply of creams and ointments that barely worked, which I would have had to apply multiple times a day to large swaths across my entire body. My face would have remained practically untreatable. Foundation was more effective than anything I could get from a medical provider. Instead, I now have a nearly complete cessation of symptoms with nothing more than a shot taken four times a year.

The lesson here is that the most seemingly dysfunctional profit-based system is usually better than even the highest-quality forms of central planning. As long as there is some way to turn ideas and innovation into products and services that people want, no matter how many barriers the government puts in the way, science will move forward. It may go faster or slower depending on the policy choices we make, but it will continue. One advanced economy allows windfall profits in the pharmaceutical space, and it is not a coincidence that ours is the one responsible for the vast majority of important medical breakthroughs.

Socialized medicine is a marshmallow test. It can provide advantages in the short run, yet it ensures that there will be fewer innovations for future generations. Even the supposed benefits are usually exaggerated and often have drawbacks, such as longer wait times for specialists and lower rates of cancer survival.

The US health care system, as silly and clunky as it looks, cured my psoriasis. More importantly, it has produced a cure that will be available as long as our species survives and does not lose the knowledge accumulated by previous generations. Some will not have the health care coverage to afford it, but eventually the patent will expire, and the drug will remain part of our shared scientific heritage.

There’s a tendency to look at the pharmaceuticals and medical treatments that exist today and declare that they should be available by right for all those who need them, removing the profit motive from the health care system. Yet it is precisely that profit motive, however messy and imperfect it is in practice, that makes such breakthroughs possible in the first place.