Child labor was once ubiquitous. Take, for example, ancient Rome. As Mary Beard noted in her 2015 book SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, “Child labour was the norm. It is not a problem, or even a category, that most Romans would have understood. The invention of ‘childhood’ and the regulation of what work ‘children’ could do only came fifteen hundred years later and is still a peculiarly Western preoccupation.” Today, fewer than 10 percent of children worldwide have to work for a living. By and large, those that do, live in poor countries. Economic growth, which was key to eliminating child labor in the developed world, can achieve the same outcome in the developing one.

Prior to the mechanization of agriculture, which increased farm productivity, there were no food surpluses to sustain idle hands – including those of children. “The survival of the family demanded that everybody contributed,” writes Johan Norberg in his 2016 book Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future. As such, “it was common for working-class children to start working from seven years of age … In old tapestries and paintings from at least the medieval period, children are portrayed as an integral part of the household economy.… [with many working] hard in small workshops and in home-based industry,” Norberg continues.

As agricultural productivity increased, people no longer had to stay on the farm and grow their own food. They moved to the cities in search of a better life. At first, living conditions were dire, with many children working in mines and factories. By the middle of the 19th century, however, working conditions started to improve. Economic expansion led to increased competition for labor and wages grew. That, in turn, enabled more parents to forego their children’s labor and send them to school instead.

Between 1851 and 1911, for example, the share of British working boys and girls between the ages of 10 and 14 dropped from 37 and 20 percent respectively to 18 and 10 percent respectively. In the United States, the share of working 10 to 13 year olds fell from 12 percent in 1890 to 2.5 percent in 1930.

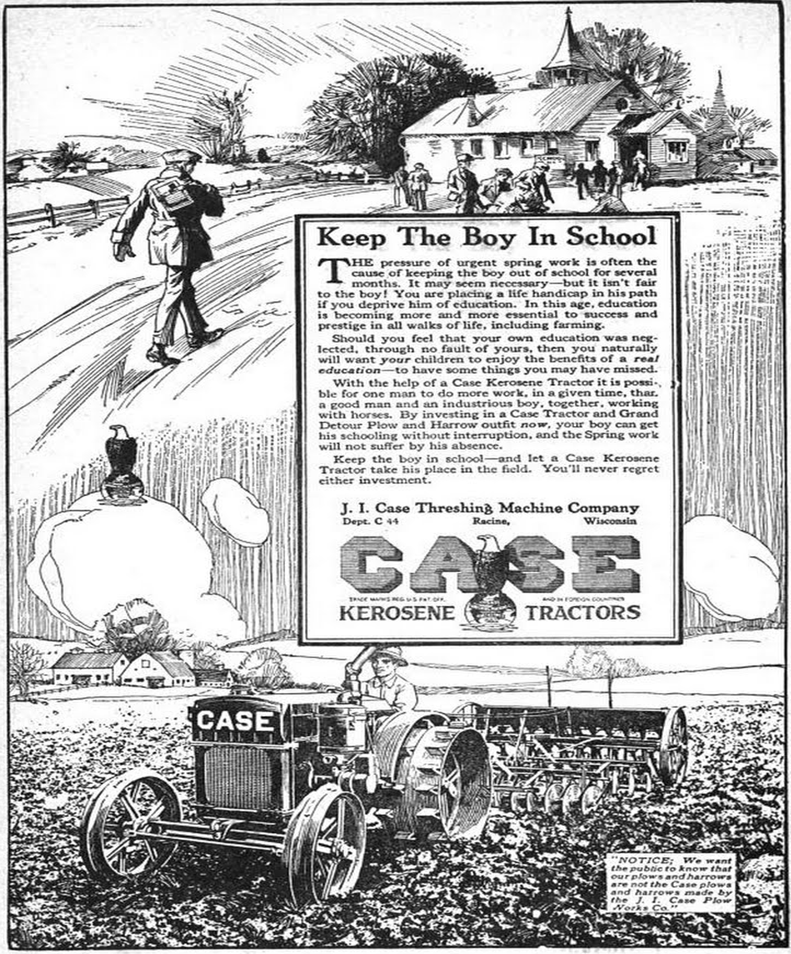

In his 2018 book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, Harvard University professor Steven Pinker recounts how technology helped get boys off the farm and into the classroom. He quotes a tractor advertisement from 1921, “By investing in a Case Tractor and Ground Detour Plow and Harrow outfit now, your boy can get his schooling without interruption, and the Spring work will not suffer by his absence. Keep the boy in school—and let a Case Kerosene Tractor take his place in the field. You’ll never regret either investment.”

While legislation eventually enshrined in law what was already happening in practice and banned child labor, it is crucial to remember that it was only after a critical mass of children were pulled out of the labor force by their parents that people realized that life without child labor was possible. Similar processes are taking place in the rest of the world today.

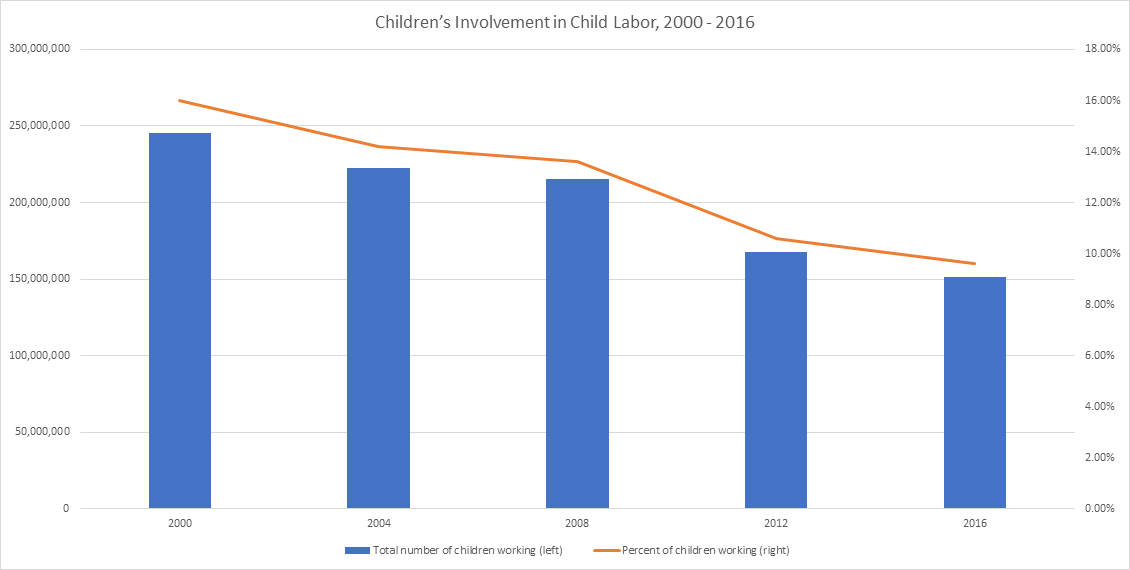

According to the International Labor Organization’s 2017 Global estimates of child labor: results and trends 2012-2016 report, child laborers as a proportion of all children aged 5 to 17 dropped from 16 percent in 2000 to 9.6 percent in 2016. That year, 19.6 percent of children worked in Africa, 2.9 percent in the Arab states, 4.1 percent in Europe and Central Asia, 5.3 percent in the Americas and 7.4 percent in Asia and the Pacific.

The total number of child laborers fell from 246 million in 2000 to 152 million in 2016. That’s a reduction of 38 percent over a relatively short period of 16 years. In 2016, almost half of child laborers lived in Africa (72.1 million), which is the world’s poorest continent. Over 62 million child laborers lived in the populous Asia and the Pacific region. Some 10.7 million lived in North and South America, 1.2 million lived in the Arab States and 5.5 million lived in Europe and Central Asia.

As was the case throughout human history, agriculture continued to dominate child employment, accounting for 71 percent of child laborers. Services employed 17 percent of child laborers and industry 12 percent. In spite of continued population growth, the International Labor Organization expects that the total number of child laborers will continue to decline, falling to between 121 and 88 million in 2025. As such, the importance of economic growth in developing countries cannot be overstated.

This first appeared in CapX.