Summary: The life of Ann Jarvis, the woman who inspired Mother’s Day, was filled with tragedies that illustrate the difficulties of motherhood in the past. With almost nonexistent prenatal care, only 4 of her 13 children reached adulthood. Learn more about the progress made in maternal and childhood health in this article by Chelsea Follett.

This article originally appeared in The Virginian‐Pilot.

Few know the story of the woman who inspired Mother’s Day. Her name was Ann Jarvis, and the many tragedies in her life demonstrate how much more difficult motherhood was in the past and the progress that has been made since.

Ann was born in 1832 in Virginia, and married at age 18. After marrying, Ann had 13 children over the course of 17 years. In that era, prenatal care was almost nonexistent. During the 19th century, about 500 to 1,000 mothers died for every 100,000 births. Giving birth 13 times, as Ann did, meant that she faced between a 6 and 13 percent chance of death. Fortunately, she survived. Today, the maternal mortality rate, while still higher in poor countries than in rich ones, is falling—decreasing from 342 deaths per 100,000 live births in the year 2000 to 211 per 100,000 in 2017, the World Bank’s most recent year of data.

Children also faced fearful survival odds and were often killed by childhood ailments that are now preventable or treatable. Ann’s family was no exception: only four of her children lived to adulthood. Her children died of illnesses such as measles, typhoid, and diphtheria, which are now far less common thanks to vaccines and better sanitation.

The grief of losing nine children is beyond the imagination of most people today. Ann faced better odds than her foremothers in this regard, although she fared worse than the statistical average. The average number of a mother’s children lost to premature death had fallen from three in 1800 to just two in 1850, the year that Ann wed. That figure fell to one child in 1900. Today, thankfully, childhood death is extraordinarily rare in developed countries, where most mothers can expect to see all of their children survive. That progress is ongoing, and has come about thanks to medical advances, improved sanitation, and rising prosperity to fund them—as well as the efforts of people like Ann.

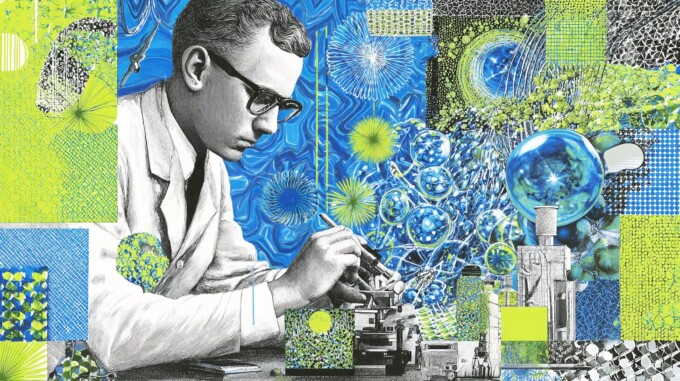

In 1858, while she was pregnant with her sixth child, Ann began organizing women’s clubs with the goal of reducing childhood death. The clubs raised funds to buy medicine for local children, hired assistants for mothers suffering from tuberculosis, brought supplies to sick quarantining households to prevent the spread of disease, and more. “The clubs inspected food and milk for contamination—long before governments took on such tasks—and they visited homes to teach mothers how to improve sanitation. Ann became a popular speaker, addressing subjects [such as] ‘Great Value of Hygiene for Women and Children.’”

Ann helped popularize the practice of boiling drinking water in her community, preventing cases of the often‐deadly waterborne illnesses (such as tuberculosis and typhoid fever) that ravaged humanity before widespread chlorination.

Despite the demands of childrearing and her volunteer work on behalf of mothers and children, Ann also found time to organize efforts during the Civil War to treat wounded soldiers from both sides. A devout Methodist, Ann was also active in her religious community and taught Sunday School lessons.

Anna, one of Ann’s four children to make it to adulthood, created Mother’s Day in Ann’s honor. She was inspired by something Ann had said during Sunday School: “I hope and pray that someone, sometime, will found a memorial ‘mother’s day’ commemorating her for the matchless service she renders to humanity in every field of life. She is entitled to it.”

Given her tireless work to improve maternal and childhood health, Ann certainly deserves credit. This Mother’s Day, despite the problems that remain, take a moment to appreciate progress in the fight against premature death for mothers and their children.