The following is adapted from a transcript of a Cato Institute event featuring a trailer and discussion of the recent documentary film “They Say it Can’t Be Done.” The event page featuring the full discussion can be found here.

Patrick Reasonover: Fantastic. Well, thank you, Chelsea, and thank you to everyone who watched our film or who will soon watch it from the link. We have a great team. I just happen to be sitting here, but there’s no way I could have made this documentary by myself. Just want to start out with some thank yous to Andrea Fuller, fellow producer; Victoria Hill, fellow producer; Michael Ozias, director of the film; as well as Dan Hanna, fantastic editor, and Ben Gaskell, our DP cinematographer. They’re just some great people behind this film, and we, on behalf of them all…I’d just like to thank everybody for watching us and also thank Cato. If you have been to Cato or work at Cato, you might have recognized some of the backgrounds in the film. So, I definitely want to thank Clark Neily, Peter Van Doren, and the Cato Events team for letting us shoot there as we were making this film.

I want to talk a little bit about the kind of thinking behind the film. Our approach to documentary is to start with a question and then go on a journey through the film, connecting these ideas to emotions and people’s experience in the world, and then to end on a deeper, more profound question than we began with…One that you could only reach by going on that journey. So, our approach is not to turn the film into a syllogism or to be a paper that you watch or you read through and see a conclusion. It’s more meant to make you reflect upon yourself and who you are and your ideas and the truth…What you believe. So, coincident with that approach, what we do is we’re approaching this subject matter, something like innovation and regulation…Which was what we started with…We want to grant The Federal Society, who was a fantastic partner on this film, to tell a story about innovation and regulation.

When you’re looking to tell a story about two ideas, it’s very challenging. People are not going to necessarily rush out to the theater to watch a feature film on regulation. So, what we did is we dove in and just said what is of interest here, what really is going to motivate audiences and make it worth their hour and a half to pay attention?

So, what we decided upon was to focus on—because we have innovation—what are some problems innovators are looking into? Because the problems the innovators are looking into is something that would be shared with our audience…People who look at hunger, providing cheap and healthy protein to growing global population, atmospheric carbon, global warming, ocean acidification, rising health care costs. These are all problems, no matter what ideology or background you come from, that we all know that we’re grappling with.

What we wanted to do is pick some of these problems and go look for innovators to see if there are indeed market solutions to these problems. Often from the media, at least from my standpoint, we see whenever these problems are announced or discussed, there is somehow an encumbrance that the government be the one to solve it in one big centralized plan. But, we thought it’d be interesting to see if through the decentralized system of the market, whether there were innovators out there who, if their innovation was taken to scale, would it impact or solve these problems. The folks that you see in the film are representative, so by no means the only people working in these fields or companies in these fields. They’re representative of them. It was just really an honor to be allowed to go into the facilities where these people are working and talk with them about their vision, and I just wanted to relay a couple takeaways, one bringing us back to regulation.

So, with the film, we wanted to see are these innovators able to bring their product to market? Are there barriers to entry? Are those barriers to entry regulatory in nature, in the sense that the current regulatory apparatuses are throwing up barriers or blocking them? Or, perhaps, there’s something more that the regulatory agency needs to do. When we looked at regulation, we took a very broad view of it. From the standpoint of the film, property rights is a form of regulation. So, we don’t talk about regulation as though it’s purely a command and control regulation where Congress passes an act and then they create an agency or they provide new rules for that agency and the agency is going to say this is what you can and cannot do, and then we’re going to enforce that proclamation and penalize you if you don’t. For us, that’s a form of regulation, but for markets to work, we need other kinds of regulations such as property rights.

We wanted to just take a big look at the whole sphere of what tools regulators could deploy and just basically test our regulatory system and see if it is helping or is it harming these innovators, and what can be done to change the situation. One of the things I found just personally going on is…You might start with a presumption, especially if you come in with sympathies towards a kind of free market view of the world, that there’s a story that’s Mr. Bad Guy regulator sitting up there in Washington in his desk chair or her desk chair looking to make life miserable for innovators out there, wishing secretly they could have done it, and the poor put upon companies are all out here just suffering under their thumb. But in fact, the story we found is much more complicated than that. There’s not necessarily supervillains sitting in bureaucracies in Washington D.C. More often, or really at a deeper place—which is why we titled our film They Say It Can’t Be Done—there’s really these two forces that are within us all: optimism and pessimism.

When it comes to something like cell cultured meat, you have crony corporations and trade associations like the American Cattle Association or the Cattlemen’s Associations that are trying to prevent this product from coming to market or damage it by saying it’s not meat, you can’t market it as meat, even though it literally scientifically and chemically is meat.

So, there’s crony corporations involved. Congress has to act to put tools in the hands of regulators or restrain them from using tools that they’re currently deploying if they don’t want them to be doing it. And then, those congresspeople are ultimately subject to the voters. So, to the extent that you yourself allow the pessimism—the view that mankind is a pernicious virus upon planet Earth and that our activities are not life-promoting and are not progress…And that when we see these big problems that come about from human activity, we just need to stop. We need to limit. There needs to be less activity. There needs to be less innovation. There needs to be fewer people. Then, you’re really giving in to something that’s really exacerbated and promoted by our media. But, it really is at base…You giving in to this belief that that’s the way mankind is.

There’s another part of us—the optimist—who can look out at strangers we don’t know, like the people in the film that you had the opportunity to spend some time with…These innovators and see what they’re doing. Just what is the human mind and its imagination capable of, especially when you have a lot of minds collaborating together to do amazing things? Then when you think about those problems, when you’ve embraced that optimistic part of yourself, there’s sort of a sense that no matter what we face—even if we create, we’re part of the problem that we’ve created—that we can solve it. It’s not going to come from a centralized, mandated place because the only way you can solve problems is by having local information, and a lot of different imaginations coming up with new ideas and competing to succeed.

So, really, when it comes to innovation and regulation, they’re tied together hand in hand. There needs to be basic regulations and traditions for innovators to bring a product to market, to patent it, to brand it, to offer it available in stores, to have contract law in courts. However, to the extent that regulation stands in the way of this, it’s standing in the way of the power of the decentralized human imagination all over the world interacting and collaborating with one another to discover solutions that maybe solve problems without even intending to. As you can see in the film, just one example of this would be if cell cultured meat is able in the future to be the way that we consume protein…Not through factory farms or just animal husbandry and slaughter. We have a lot of domino effects where two-thirds of arable land is used to grow food to feed those animals. Currently, there’s water usage, there’s waste products from those animals. Those animals are given antibiotics. So, we almost see an immediate environmental impact just by shifting to a system like that.

I think the beauty of it and the magic of it is really embodied in one of the quotes Josh Tetris gave us in the film, which is that they’re not necessarily a company setting out to do good. They are companies setting out to make the best damn hamburger you ever ate at the lowest price, and when they have that motivation, they’re able to do good.

So, I hope you enjoyed the film and I’m very eager to hear your questions, and I’m also eager to hear from Johan.

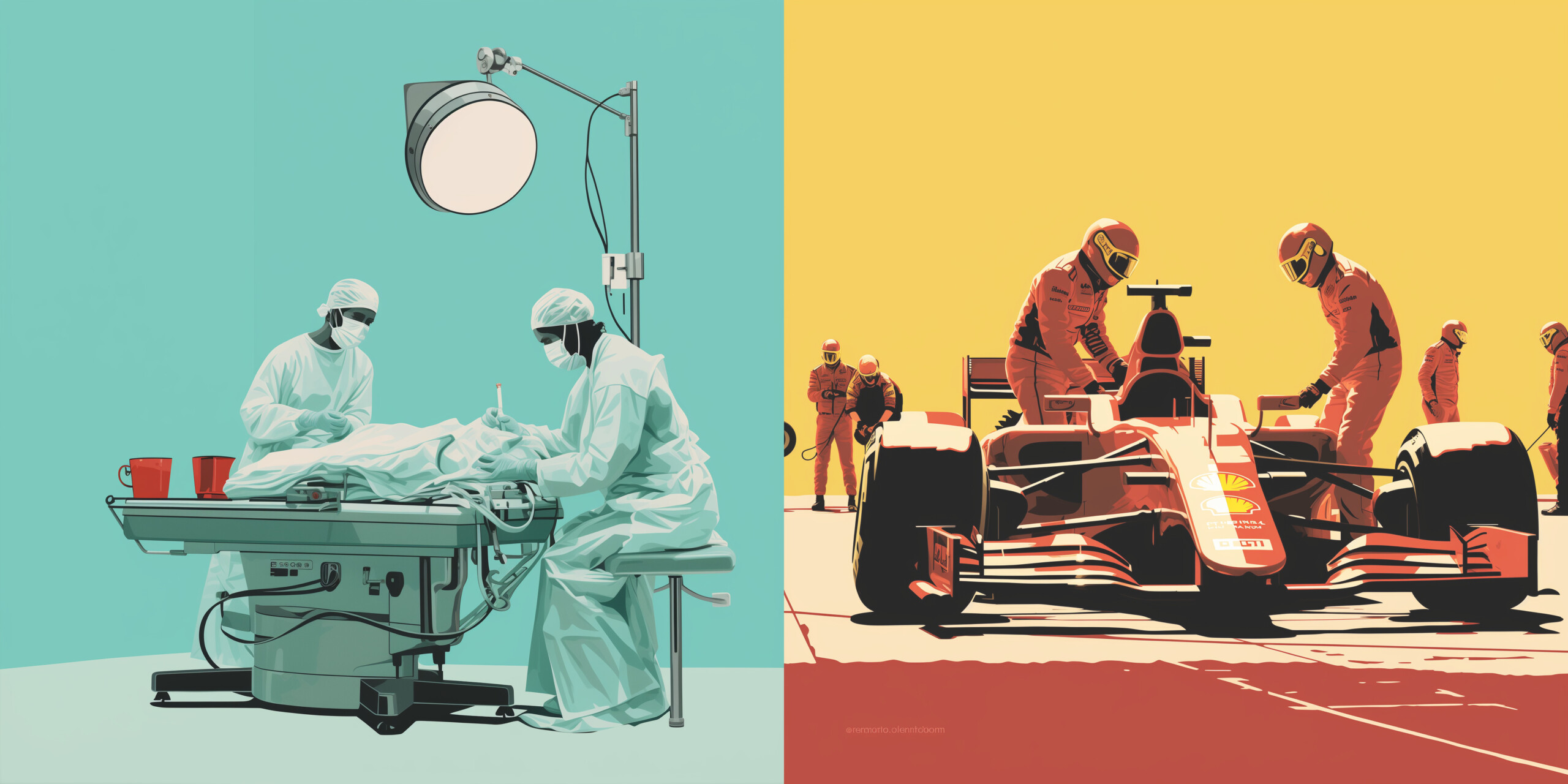

Johan Norberg: So, thank you, Chelsea, so much, and thank you, Patrick, and congratulations. I’m doing regular basis documentaries myself, so I think I know what I’m talking about when I say that this is a great film. It is very well done. It’s an important topic, and I love the use of the team America thunderbirds puppets, which is really clever, I think. But, I also have to say that I watched it with mixed emotions, and I think that that’s probably your intention as well, because it’s a powerful description of what happens when the unstoppable force of human imagination and creativity meets the immovable object of government regulation.

We meet these amazing entrepreneurs and innovations with tremendous potential to improve the world and all our lives and to protect the planet, and yet, all the rules and regulations that stop them at every turn. So, it’s really mixed emotions. It’s like bringing a kid to a candy store but saying that he can’t have anything.

I don’t have to dwell on the particular examples in the film. You have probably all seen it. If you haven’t, congratulations, because you have 90 great minutes ahead of you. So here, I would just like to distill and focus on some of the lessons and the things that I thought about when I watched this film.

First of all, in my new book, my forthcoming book—Open: The Story of Human Progress—that Chelsea mentioned, I point out that innovation comes from surprises and accidents, from strange places, from weird combinations, from eccentrics and entrepreneurs, and it cannot be foreseen, and it cannot be planned. From the steam engine to the personal computer to present innovations, we see this pattern of innovations coming from strange places where we didn’t expect them to. Robotics just solved the ancient problem of simultaneous localization of the robot and mapping by learning from gaming and gaming companies. Newspapers and retailers learned secure online payments and video streaming from porn sites. So, it comes from surprises and strange combinations, and the problem is that nobody really likes surprises…Because we all try to get what we are doing all the time to work.

We’re trying to get our whole business model to work, politicians try to get their social and economic models to work, and they don’t want anyone to disrupt that, and that’s an age-old problem. The economist and historian Joel Mokyr talks about Cardwell’s, after the technology historian Donald S. Cardwell. Cardwell’s Law says that even the best of cultures, even in the golden eras, they tend to move towards an absorbing barrier of technological stagnation, because innovation always faces resistance from groups that think that they stand to lose from it for one reason or the other another…Be they old political or religious elites or business infants with old technologies or workers without motive skills, could be nostalgic romantics, or just people who are afraid of the risks that come with new technologies.

All these groups have an incentive to stop changes with bans and regulations and monopolies and burning of boats or building of walls, and when they get sufficient power, they block surprises, and that is how every period of openness and innovation in history has ended—except one. The one that we’re in right now. For the moment, as is pointed out in this film, it is neck and neck between innovation and regulation, between optimism and pessimism. The forces of pessimism and of regulation are strong because of two incentives that make this problem of regulation intractable—the incentives for bureaucrats and for businesses. They are both on wide display in this film. It’s countless examples of these incentives for bureaucrats and for businesses.

To start with the bureaucrats incentives, it really goes back to Bastiat’s, the French 19th-century economist, What is Seen and What is Not Seen. Clark Neily points this out in the film. You can see the immediate positive effects of regulation and government intervention, but the costs are not seen because they’re widespread, dispersed in time and in space so that you don’t see the great thing that could come about from innovation from new businesses. This is what every poor bureaucrat who is not a supervillain, as Patrick pointed out…But what every bureaucrat faces whenever they are supposed to decide on whether to give the go-ahead or not, and we would face this problem as well if we were in their position.

Let’s say you’re an FDA official looking at a new medical technology or a new drug. You can make two very different mistakes. The first mistake is to approve a drug that turns out to have side effects that result in the death or serious injury to a sizable number of people. That’s the first mistake you could make. The other one is that you can refuse approval of a drug that could have saved many lives or relieved great distress without any serious side effects. The question is, what would you rather do? Which kind of mistake would you rather do? It’s pretty obvious, isn’t it, because in the first instance, you’ll see those who are hurt by your approval; you know who they are, or at least journalists know who they are…You live with the consequences, and you will get the blame. In the second instance, when you ban this drug, you do not give a go-ahead, no one will know how many people could have been saved, and you don’t look them in the eye. Even if you had to, you’d have a perfect excuse—you just wanted to keep everybody safe. We would probably all err on the safe of bans, of conservatism. It’s obvious, but it’s really just based on psychology and the fear of facing blame, because the real consequences of our actions are the same. We hurt people no matter what kind of mistake we do, and often much, much worse when you restrict innovation because we don’t live in a perfect world. We need inventions.

So, every time the FDA says that they have just approved a new medical technology or a new drug that will save the lives of 20,000 people a year, it really means that they have killed 20,000 people every year that they kept it off the market, but it doesn’t feel like it. So, regulation will always be extremely conservative unless pushed in the other direction. But unfortunately, it’s not pushed in that direction, but on the contrary, in the other direction, and that’s partly because of the second incentive—the incentive of businesses…And not businesses in the marketplace, but businesses in the market for regulation. If authorities want to minimize risks, corporations want to minimize the risk to their businesses. You know the old truth that monopolies are just like babies; nobody likes babies until they have their own, and then suddenly it’s the best thing on the planet, and it’s the same thing with the monopolies, obviously. So, as the film points out, big business love regulation, because they’re in a perfect position to handle regulations. The more regulation, the more difficult for new possible entrants in their sector, the fewer competitors.

Milton Friedman talked about the natural history of government intervention, and it goes something like this: there is a real evil or a fancy evil that leads to a demand to do something about it, and then there is a coalition between sincere high-minded reformers that want to keep us all safe and equally sincere interested parties often in business. They come up with a new law, and the preamble to the law talks about the public interest, and the body of the law grants power to government officials to do something. Once this happens, the high-minded reformers, they experience a glow of triumph, and they turn their attention to new courses. They move on to the next ambition. This leaves us with the equally sincere interested parties who stay put and make sure that the regulations are tailored to their old business models, to their processes, to their technologies, to their goods and services, and so keeps the competition away…Because they have the most at stake, and they have the most knowledge about these issues, and it’s worth everything for them to capture the regulatory system. That’s what regulation does: it gives these incumbent businesses a new power that they wouldn’t have in the marketplace.

So, in other words, there are strong incentives and powerful constituencies for old ways of doing stuff, and we see that on proud display in this film. The only thing that doesn’t have a pressure group and a constituency is the future, so we have to be that constituency as individuals, businesses, think tanks, politicians, filmmakers who know what’s at stake…Because we need that space for surprises to make the world safe for progress.

So again, Patrick, thank you for this wonderful work, and please pass on my gratitude to the whole team showing us what’s at stake and making these issues very concrete and convincing. I’ll just leave you with this: there are many strong and moving stories here about the lives that can be saved through artificial organs, promise of carbon capture lab-grown meat that could end cruelty against animals and save lots of land. But if I had to pick just one story, I’d say that the most moving sequence is the entrepreneur working on aquaculture, who points out that he got into this line of business because he just loves the ocean—being in it, being on a boat and diving and working, thinking about it, and how much he hates the fact that nowadays, he rarely gets to go there now because now he’s always stuck behind a computer fighting against bureaucrats for permits.

That got to me. You might not believe in his dream, and it might not work out in the end, but he’s devoting his life and risking his fortune to save the planet and improve our lives, so can we at least please stop repaying him by making his life miserable? Thank you.