For most of human history, life was very difficult for most people. People lacked basic medicines and died relatively young. They had no painkillers, and people with ailments spent much of their lives in agonizing pain. Entire families lived in bug-infested dwellings that offered neither comfort nor privacy. They worked in the fields from sunrise to sunset, yet hunger and famines were commonplace. Transportation was primitive, and most people never traveled beyond their native villages or nearest towns. Ignorance and illiteracy were rife. The “good old days” were, by and large, very bad for the great majority of humankind.

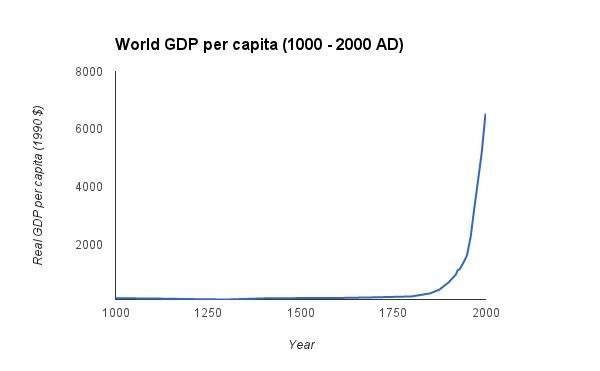

Average global life expectancy at birth hovered around 30 years from the Upper Paleolithic to 1900. Even in the richest countries, such as those of Western Europe, life expectancy at the start of the 20th century rarely exceeded 50 years. Incomes were quite stagnant, too. At the beginning of the Common Era (CE), annual GDP per person around the world ranged from $600 to $800. As late as 1820, it was only $712 (measured in 1990 international dollars).

Humanity has made enormous progress—especially over the course of the past two centuries. For example, average life expectancy in the world today is almost 72 years. In 2010, global GDP per person stood at $7,814—over 10 times more than two centuries ago (measured in 1990 international dollars).

It is not only income and life expectancy that are improving. Steven Pinker, professor of psychology at Harvard University, has noted a propitious decline in physical violence. As Pinker writes,

Tribal warfare was nine times as deadly as war and genocide in the 20th century. The murder rate in medieval Europe was more than thirty times what it is today. Slavery, sadistic punishments, and frivolous executions were unexceptionable features of life for millennia, then were suddenly abolished. Wars between developed countries have vanished, and even in the developing world, wars kill a fraction of the numbers they did a few decades ago. Rape, hate crimes, deadly riots, child abuse—all substantially down.

If anything, the speed of human progress seems to be accelerating. As Charles Kenny of the Center for Global Development writes,

4.9 billion people—the considerable majority of the planet—[live] . . . in countries where GDP [gross domestic product] has increased more than fivefold over 50 years. Those countries include India, with an economy nearly 10 times larger than it was in 1960, Indonesia (13 times), China (17 times), and Thailand (22 times larger than in 1960). And 5.1 billion people live in countries where we know incomes have more than doubled since 1960, and 4.1 billion—well more than half the planet—live in countries where average incomes have tripled or more . . . .

According to a 2011 paper by Brookings Institution researchers Laurence Chandy and Geoffrey Gertz,

[The] rise of emerging economies has led to a dramatic fall in global poverty . . . [The authors] estimate that between 2005 and 2010, the total number of poor people around the world fell by nearly half a billion, from over 1.3 billion in 2005 to under 900 million in 2010. Poverty reduction of this magnitude is unparalleled in history: never before have so many people been lifted out of poverty over such a brief period of time.

Similarly, the world’s daily caloric intake per person has increased from an average of 2,264 in 1961 to 2,850 in 2013. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the caloric intake increased from 2,001 to 2,448 over the same time period. To put these figures in perspective, the U.S. Department of Agriculture recommends that moderately active adult men consume between 2,200 and 2,800 calories a day and moderately active women consume between 1,800 and 2,000 calories a day.

The internet, cell phones, and air travel are connecting ever more people—even in poor countries. More children, including girls, attend schools at all levels of education. There are more women holding political office and more female CEOs (chief executive officers). In wealthy countries, the wage gap between genders is declining. Our lives are not only longer, but also healthier. The global prevalence rate of people infected with HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome) has been stable since 2001 and deaths from the disease are declining because of the increasing availability of anti-retroviral drugs. In wealthy countries, most cancer rates have started to fall. That is quite an accomplishment considering that people are living much longer and the risk of cancer increases with longevity. In parts of the world, dwellings are growing ever larger. Workers tend to work fewer hours and suffer from fewer injuries. That’s especially true in developed countries, like the United States. Shops are bursting with a mind-boggling array of goods that are, normally, less expensive and of higher quality than in the past. We enjoy more leisure and travel to more exotic destinations.

Is everything getting better? Not exactly. In recent years, the world has witnessed a sustained attack on political and economic freedoms, as well as freedoms of religion and free expression. Considering that human freedom is an integral part of human progress, these worrying developments are worth bearing in mind.

Progress Is Not Linear

Unfortunately, progress is not linear. Europe, for example, experienced an unprecedented period of peace and rapidly improving standards of living between the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Between 1820 and 1914, real or inflation-adjusted GDP per person rose by 127 percent in Western Europe. In Great Britain, for example, life expectancy at birth rose from 41 years 1818 to 53 years in 1914. In Sweden, the improvement was even more dramatic, with life expectancy rising from 39 years in 1814 to 58 years in 1914.

The period between the start of the 20th century and the outbreak of World War I saw the introduction of such life-changing technologies as the radio, the vacuum cleaner, air conditioning, the neon light, the airplane, sonar, the first plastics, the Ford Model T automobile, and cornflakes.

As a result of World War I, which raged between 1914 and 1918 and killed some 16 million people, per-person GDP in Western Europe fell by 11 percent between 1916 and 1919. Life expectancy in Great Britain, one of the war’s main participants, dropped from 53 years in 1914 to 47 years in 1918. Other horrors followed.

The devastation of World War I undermined the Russian monarchy, leading to the rise of communism and the establishment of the USSR. Globally, some 100 million people died because of purges and socialist economic mismanagement in communist countries. Defeat in World War I and harsh reparation demands led to resentment in Germany. That contributed to the rise of National Socialism (Nazism), the outbreak of World War II, and the subsequent Holocaust. Some 73 million people died in World War II. After the war ended, communist dictatorships and free-market democracies fought in a variety of proxy conflicts as part of the Cold War, including the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

In spite of all that suffering, humanity rebounded. New technologies were introduced. They included the microwave oven, the mobile phone, the transistor, the video recorder, the credit card, the television, solar cells, optic fiber, microchips, lasers, the calculator, fuel cells, the World Wide Web, and the computer. Medical advances included penicillin; cortisone; the pacemaker; artificial hearts; the MRI scan; HIV protease inhibitor; and vaccines for hepatitis, smallpox, and polio.

Over the course of the 20th century, the GDP of an average Western European rose by 517 percent. For life expectancy, a typical Frenchman could expect to live 34 years longer in 1999 than in 1900.

The United States escaped much of the devastation of the two world wars, but suffered the Great Depression and carried many of the burdens of the Cold War. Between 1929 and 1933, for example, the average U.S. GDP per person declined by 31 percent. It was not until 1940 that it returned to its pre-Depression levels. Over the course of the 20th century, however, average American GDP per person rose by 581 percent and life expectancy by 28 years.

In Asia, average GDP per person rose by 96 percent between 1913 and 1999. Over the same time period, Chinese GDP per person rose by 473 percent and Indian by 173 percent. In China, life expectancy rose from 32 years in 1930 to 71 years in 1999—an increase of 39 years. Indian life expectancy increased from 24 years in 1901 to 61 years in 1999—an increase of 37 years.

The story of Africa is more complex, but still, on balance, positive. Between the time of the European colonization in 1870 and African independence in 1960, a typical inhabitant of the African continent saw his or her GDP rise by 63 percent. Per-person GDP increased by a further 41 percent between 1960 and 1999. Whereas Africa had underperformed relative to the rest of the world, Africans were better off at the end of the 20th century than they were at the beginning. Moreover, since the start of the new millennium, Africa has been making up for lost time. According to the World Bank, average per-person GDP in Sub-Saharan Africa rose by 38 percent between 2001 and 2016.

When it comes to life expectancy, Africa has experienced much progress. However, increases in life expectancy vary, depending on the harm caused by the spread of AIDS. Life expectancy in hard-hit South Africa, for example, rose from 45 years in 1950 to an all-time high of 62 years in 1990. It dropped to 53 years in 2005, before rebounding to 62 years in 2015.

Progress Is Not Inevitable

When reflecting on the world today, it is important to keep human development in proper perspective. The present, for all of its imperfections, is a vast improvement on the past. Understanding and appreciating the progress that humanity has made does not mean that we stop trying to make the future even better than the present. As the University of Oxford philosopher Isaiah Berlin once wrote, “The children have obtained what their parents and grandparents longed for—greater freedom, greater material welfare, a juster society: but the old ills are forgotten, and the children face new problems, brought about by the very solutions of the old ones, and these, even if they can in turn be solved, generate new situations, and with them new requirements—and so on, forever—and unpredictably.”

That said, we should avoid making two mistakes. First, we should correctly identify, preserve, and expand those policies and institutions that made human progress possible. If we misidentify the causes of human progress, we could put the well-being of future generations at risk. One way of avoiding serious policy mistakes in the future is to avoid concentrating power in a single pair of hands or in the hands of a small elite. Instead, we should trust in the choices made by free-acting individuals. No doubt, some of those individual choices will turn out to be bad, but the aggregate wisdom of millions of free-acting individuals is more likely to be correct than incorrect.

Second, we should beware of utopian idealism. Utopians compare the present with, so to speak, future perfect, not past imperfect. Instead of seeing the present as a vast improvement on the past, they see the present as failing to live up to some sort of an imagined utopia. Unfortunately, the world will never be a perfect place because the human beings who inhabit it are themselves imperfect. Today, it is difficult to imagine the emergence of a powerful new utopian movement. But few people in 1900 foresaw the destruction brought on by communism and Nazism. We cannot rule out that utopian demagogues akin to Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao Zedong, or Pol Pot will emerge in the future.

Sources of Progress

When it comes to the standard of living, human history resembles a hockey stick, with a long straight shaft and an upward-facing blade. For thousands of years, economic growth was negligible (resembling that long straight shaft). At the end of the 18th century, however, economic growth and, consequently, the standard of living, started to accelerate in Great Britain and then in the rest of the world (resembling that upward-facing blade). What was responsible for that acceleration?

The Nobel Prize–winning economist Douglass North, for example, argued that changing institutions, including the evolution of constitutions, laws, and property rights, were instrumental to economic development. The University of Illinois at Chicago economist Deirdre McCloskey attributed the origins of “the great enrichment” to changing attitudes about markets and innovation. The Harvard University psychologist Steven Pinker contended that material and spiritual progress were rooted in the Enlightenment and the concomitant rise of reason, science and humanism.

Whatever the case may be, a confluence of fortuitous events allowed for the breakout of the industrial revolution and enhanced the process of globalization. Let us look at those two in greater detail. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the industrial revolution was “the process of change from an agrarian, handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacture.” It started in Great Britain in the 18th century and then spread to other parts of the world.

The technological changes included the following: (1) the use of new basic materials, chiefly iron and steel, (2) the use of new energy sources, including both fuels and motive power, such as coal, the steam engine, electricity, petroleum, and the internal-combustion engine, (3) the invention of new machines, such as the spinning jenny and the power loom that permitted increased production with a smaller expenditure of human energy, (4) a new organization of work known as the factory system, which entailed increased division of labor and specialization of function. . . . These technological changes made possible a tremendously increased use of natural resources and the mass production of manufactured goods. . . . There were also many new developments in nonindustrial spheres, including the following: (1) agricultural improvements that made possible the provision of food for a larger nonagricultural population, (2) economic changes that resulted in a wider distribution of wealth, the decline of land as a source of wealth in the face of rising industrial production, and increased international trade, (3) political changes reflecting the shift in economic power, as well as new state policies corresponding to the needs of an industrialized society, (4) sweeping social changes, including the growth of cities, the development of working-class movements, and the emergence of new patterns of authority, and (5) cultural transformations of a broad order.

Not everyone was happy about the industrial revolution, however. Contemporary observers such as Charles Dickens commented on the squalor of 19th-century cities and the backbreaking labor of the people, including children, in the factories in much the same way that our journalists today comment on the squalor of the rapidly industrializing Indian cities and the backbreaking labor of people, including children, in Bangladeshi factories.

But things should be kept in a proper perspective. Life on an 18th-century farm was extremely difficult, and the city offered the former country dwellers higher wages and new opportunities. In time, sanitation, health care, and other benefits of civilized life caught up with the cities’ rising population, giving us the modern metropolis. In a similar vein, legislation caught up with rising standards of living and codified in law what already was happening in practice—as productivity increased and wages rose, fewer children were needed to supplement their parents’ incomes. Increased productivity of workers led to greater competition for workers, and factory owners started taking better care of their employees. Working conditions improved, and work injuries declined.

Another major criticism of the industrial revolution concerns the spoliation of the environment and exploitation of natural resources. In his famous 1808 poem Jerusalem, for example, William Blake bemoans the “satanic mills” (i.e., factories) that in his view pockmarked the bucolic face of the English countryside. But, as was the case with other writers of the Romantic era, Blake’s description of pre-industrial society was highly idealized. The reality, alas, was much less appealing. Most pre-industrial societies, Great Britain included, were heavily dependent on agricultural output. Agricultural production was labor intensive, but productivity was very low. Before the arrival of machines powered by steam and combustion engines, agriculture depended on much less efficient human and animal labor. People and animals had to be fed, which meant that most of the calories produced on the farm were immediately consumed by the laborers.

Before the industrial revolution, there were no synthetic fertilizers, such as nitrogen, and crop yields were much lower than what they are today. As a consequence, more land was required to feed people and pack animals. Land clearing was usually accomplished by the burning of forests. Yet more trees were cut down to heat houses and to cook food. Environmental damage aside, a major reason for switching from wood to coal was the simple fact that there were very few trees left. Thanks to the use of fossil fuels, global forest coverage has stabilized and is expanding in the world’s richest and most industrial countries.

Let us now turn to globalization, which the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defines as “an increasing internationalization of markets for goods and services, the means of production, financial systems, competition, corporations, technology, and industries. Amongst other things this gives rise to increased mobility of capital, faster propagation of technological innovations, and an increasing interdependency . . . of national markets.”

Contrary to the common misperception, globalization is not a new phenomenon. The trade links between the Sumer and Indus Valley civilizations go back to the third millennium BCE. Then there was the Silk Road between Europe and Asia, and European voyages into India and the Americas. Clearly, trade has been fundamental to the process of globalization from antiquity. But, why do people trade?

Trade delivers goods and services to people who value them most. An additional ton of corn produced in Kansas may be of little importance to the people in the American Midwest, but it can be crucial to the people living in drought-stricken East Africa. Trade, to use economic jargon, improves efficiency in the allocation of scarce resources. Another reason for trade is the principle of comparative advantage. As the Nobel Prize–winning economist Paul Samuelson noted,

The gains from trade follow from allowing an economy to specialize. If a country is relatively better at making wine than wool, it makes sense to put more resources into wine, and to export some of the wine to pay for imports of wool. This is even true if that country is the world’s best wool producer, since the country will have more of both wool and wine than it would have without trade. A country does not have to be best at anything to gain from trade. The gains follow from specializing in those activities which, at world prices, the country is relatively better at, even though it may not have an absolute advantage in them. Because it is relative advantage that matters, it is meaningless to say a country has a comparative advantage in nothing. The term is one of the most misunderstood ideas in economics, and is often wrongly assumed to mean an absolute advantage compared with other countries.

Moreover, trade allows consumers to benefit from more efficient production methods. For example, without large markets for goods and services, large production runs would not be economical. Large production runs are instrumental to reducing product costs. For example, early cars had to be individually handcrafted. The Model T assembly line revolutionized car manufacturing and allowed the Ford Motor Company to slash the price of the Model T from $850 in 1909 to $260 in the 1920s. Lower production costs, in other words, lead to cheaper goods and services, and that raises real living standards.

Besides better resource allocation and greater specialization and economies of scale, trade encourages technological and cultural exchanges between previously disconnected civilizations. It is for those reasons that great commercial cities like Florence and Venice during the Renaissance, and London and New York today, also tend to be centers of cultural life and technological progress.

The development of the steam engine and the opening of the Suez Canal in the 19th century made seafaring faster and cheaper. The volume of traded goods greatly increased. Through the process of price convergence, prices fell and consumers benefited. The gold standard and the invention of the telegraph—and later the telephone—also allowed for massive transfers of capital. Attracted by higher profits, capital flowed from more developed to less developed countries, thus stimulating global economic development. As the British economist John Maynard Keynes recalled, before World War I,

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth. . . . He could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages. . . . He could secure . . . cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or other formality.

This “golden age” of globalization ended with the outbreak of World War I and the concomitant disruption of world trade. By some estimates, globalization did not reach its pre–World War I levels until the 1970s or even 1980s. In fact, it was the 1980s that marked the beginning of the period of globalization that we live in today. Spurred by economic deregulation within countries, trade liberalization between countries, privatization of state-owned companies, further improvements in transport, and the arrival of the internet, globalization got a new lease on life.

The World Is Getting Better, But Skepticism Remains

As can be seen, Europe and America and, later, other regions of the world, experienced previously unimaginable improvements in standards of living. The process of rapid improvement that started in the early 1800s continues to this day. Accordingly, historical evidence makes a potent case for optimism. Yet optimism about the current state and future well-being of humankind is difficult to come by. As author Matt Ridley writes in his book, The Rational Optimist,

If . . . you say catastrophe is imminent, you may expect a MacArthur genius award [the MacArthur Fellowship or Genius Grant] or even the Nobel Peace Prize. The bookshops are groaning under ziggurats of pessimism. The airwaves are crammed with doom. In my own adult lifetime, I have listened to the implacable predictions of growing poverty, coming famines, expanding deserts, imminent plagues, impending water wars, inevitable oil exhaustion, mineral shortages, falling sperm counts, thinning ozone, acidifying rain, nuclear winters, mad-cow epidemics, Y2K computer bugs, killer bees, sex-change fish, global warming, ocean acidification, and even asteroid impacts that would presently bring this happy interlude to a terrible end. I cannot recall a time when one or other of these scares was not solemnly espoused by sober, distinguished, and serious elites and hysterically echoed by the media. I cannot recall a time when I was not being urged by somebody that the world could only survive if it abandoned the foolish goal of economic growth. The fashionable reason for pessimism changed, but the pessimism was constant. In the 1960s the population explosion and global famine were top of the charts, in the 1970s the exhaustion of resources, in the 1980s acid rain, in the 1990s pandemics, in the 2000s global warming. One by one these scares came and (all but the last) went. Were we just lucky? Are we, in the memorable image of the old joke, like the man who falls past the first floor of the skyscraper and thinks ‘So far so good!’? Or was it the pessimism that was unrealistic?

Ridley’s recollection raises an interesting question: Why are we as a species so willing to believe in doomsday scenarios that never quite materialize in practice?

In their 2012 book, Abundance: The Future Is Better Than You Think, Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler offer one plausible explanation. Human beings are constantly bombarded with information. Because our brains have a limited computing power, they have to separate what is important, such as a lion running toward us, from what is mundane, such as a bed of flowers. Because survival is more important than all other considerations, most information enters our brains through the amygdala—a part of the brain that, as Diamandis and Kotler write, is “responsible for primal emotions like rage, hate, and fear.” Information relating to those primal emotions gets our attention first because, as the authors write, the amygdala “is always looking for something to fear.” Our species, in other words, has evolved to prioritize bad news.

As Harvard’s Pinker writes in his 2018 book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, “the nature of news . . . interact[s] with the nature of cognition to make us think that the world is getting worse. News is about things that happen, not things that don’t happen. We never see a journalist saying to the camera, ‘I’m reporting live from a country where a war has not broken out. . . .’” (p. 44). Consequently, newspapers and other media tend to focus on the negative. As the old saying among journalists goes, “If it bleeds, it leads.” To make matters worse, social media makes bad news immediate and more intimate. Until relatively recently, most people never learned about the countless wars, plagues, famines, and natural catastrophes that happened in distant parts of the world. Contrast that with the 2011 Japanese tsunami disaster, which people throughout the world watched unfold as it was happening on their smart phones.

The human brain also tends to overestimate danger because of what psychologists call “the availability heuristic.” Simply put, “people estimate the probability of an event by the ease with which instances come to mind. . . . But whenever a memory turns up high in the result list of the mind’s search engine for reasons other than frequency—because it is recent, vivid, gory, distinctive, or upsetting—people will overestimate how likely it is in the world. . . . People rank tornadoes (which kill about 50 Americans a year) as a more common cause of death than asthma (which kills more than 4,000 Americans a year), presumably because tornadoes make for better television” (Pinker, p. 44).

Another bias “can be summarized in the slogan ‘Bad is stronger than good.’ . . . How much better can you imagine yourself feeling than you are feeling right now? How much worse can you imagine yourself feeling? The answer to the second question is: it’s bottomless. The asymmetry in mood can be explained by an asymmetry in life. . . . How many things could happen to you today that would leave you much better off? How many things could happen that would leave you much worse off? The answer to the second question is: it’s endless. . . . The psychological literature confirms that people dread losses more than they look forward to gains, that they dwell on setbacks more than they savor good fortune, and that they are stung more by criticism than they are heartened by praise” (Pinker, p. 50).

Furthermore, good and bad things “unfold on different timelines” (Pinker, p. 44). Bad things, such as plane crashes, can happen quickly. Good things, such as humanity’s struggle against HIV/AIDS, tend to happen incrementally and over a long period of time. As Kevin Kelly, founding executive editor of Wired magazine, wrote, “Ever since the Enlightenment and the invention of Science, we’ve managed to create a tiny bit more than we’ve destroyed each year. But that few percent positive difference is compounded over decades in to what we might call civilization. . . . [Progress] is a self-cloaking action seen only in retrospect” (The Inevitable: 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future, p. 13).

Clearly, humanity suffers from a negativity bias. Consequently, there is a market for purveyors of bad news, be they doomsayers who claim that overpopulation will cause mass starvation or scaremongers who claim that we are running out of natural resources. Politicians, too, have realized that banging on about “crises” increases their power and can get them reelected and may also lead to prestigious prizes and lucrative speaking engagements. Thus politicians on both left and right play on our fears—from crime supposedly caused by playing violent computer games to health maladies supposedly caused by the consumption of genetically modified foods.

Conclusion

By definition, a world that is populated by flawed human beings cannot be a perfect place. As long as there are people who go hungry or die from preventable diseases, there will always be room for improvement. To that end, everyone has a role to play in helping those in need. By focusing on long-term trends and comparing living standards between two or more generations, however, it is possible to observe much improvement. That improvement is not linear or inevitable, but it is real.