Summary: The decline in global birth rates has shifted concerns from overpopulation to potential economic and existential crises. Economist Julian Simon posited that humans are the ultimate resource due to their abilities to solve scarcity problems, but it’s also their need for meaningful existence that drives societal progress. As birth rates fall, it’s crucial to recognize the profound role of family and social connections in providing purpose and motivating efforts that enhance human flourishing and ensure a better future for coming generations.

Birth rates dropping below replacement level in much of the world has become a growing concern. However, this is a relatively recent worry. For a long time, the rapid growth of the world’s population led many experts to fear the depletion of our natural resources and the potential collapse of civilization. The late economist Julian Simon did not share these overpopulation concerns. Instead, he argued that humans are the ultimate resource, proposing that more humans would actually help solve our scarcity problems. His reasoning was that more humans means more brain power, which in turn leads to more discoveries, creations, and innovations. This insight is crucial. As Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley detail in their excellent book, Superabundance, our species has demonstrated a remarkable ability to leverage our cognitive capacities to solve scarcity issues throughout history.

However, there is another crucial factor to consider when thinking about what makes humans the ultimate resource. The cognitive capacities that make us an intellectual species, combined with our distinctly human self-conscious emotions, also make us an existential species driven to find and maintain meaning in life. We don’t merely seek to survive; we want our lives to matter. We aspire to play a significant role in a meaningful cultural drama that transcends our individual existence. This deep-seated need for meaning is a fundamental aspect of the human experience, shaping our goals, decisions, and actions. Critically, our need for meaning plays a central role in individual and societal flourishing.

Meaning is more than a feeling; it is a self-regulatory and motivational resource. When we find meaning in life, it provides us with a compelling reason to get up each day and strive to do our best, even in the face of challenges and setbacks. Inevitably, we will encounter failures, make mistakes, and have moments of weakness when we act impulsively or allow bad habits and patterns of living to shift our attention away from the goals and actions that would make life more fulfilling. We may also let our character flaws derail us from time to time. However, when we perceive our lives as meaningful, we are more likely to believe that we have a strong reason to work harder at self-improvement, to course correct when needed, and to persistently pursue our potential while prioritizing what matters most to us. Indeed, research has shown that the more people view their lives as full of meaning, the more they tend to be physically and mentally healthy, goal focused, persistent, resilient, and successful in achieving their objectives.

Crucially, our need for meaning is inherently social. No matter what specific activity we are engaged in, we derive the greatest sense of meaning from it when we believe that it has a positive impact on the lives of others.

Years ago, I was invited to give a presentation to professors on how to improve their public outreach efforts. During the Q&A session, a math professor expressed his doubts about the relevance of my presentation to his field. He said that it’s easy for me, as a psychologist, to engage the public because people are inherently interested in the topics psychologists study. However, he wondered how he could get people interested in hearing about math. He noted that most people find it boring. I asked him why he became a math professor. He responded that he finds the work intrinsically interesting and really enjoys sharing that passion with eager students. I then asked him why that matters – why is it important to mentor the next generation of mathematicians? He replied, “Because math is fundamental to the continuation of civilization.” As he said those words, I could see the realization dawn on him that my presentation was, in fact, applicable to his field. The central theme of my talk was that for academic scholars to succeed in public outreach, they need to be able to articulate the social significance of their work to non-experts.

However, being able to identify the social significance of one’s work isn’t just about public outreach; it’s also crucial for one’s own ability to find personal fulfillment in their work. I believe that one of the reasons people lose passion for their work, even if they are highly successful, is that they don’t believe it makes a real difference in the world. Regardless of the nature of their work, whether paid or unpaid, people are most likely to derive meaning from it when they recognize its social significance. For instance, research shows that employees are more likely to find their work meaningful when they focus on how it positively impacts the lives of others, rather than on how it advances their own career goals.

I’m emphasizing the social nature of meaning because it is essential to understanding why humans are the ultimate existential resource. The motivational power of meaning is derived from our connections with other humans and the impact we have on their lives. They are the existential resource that inspires us to tackle significant challenges and advance human progress, ensuring that future generations can enjoy a better life than we do today.

In an article published earlier this week by USA Today, I discuss this issue in the context of the current birth rate decline, focusing on the special role that family plays in our search for meaning. Individuals can certainly live meaningful lives without having children or close family relationships. There are many paths to achieving social significance by making contributions through entrepreneurship, science, art, education, mentorship, leadership, service, and philanthropy. However, for the majority of people, family remains an essential component of a meaningful life, providing a deep sense of belonging and continuity that extends beyond one’s own existence.

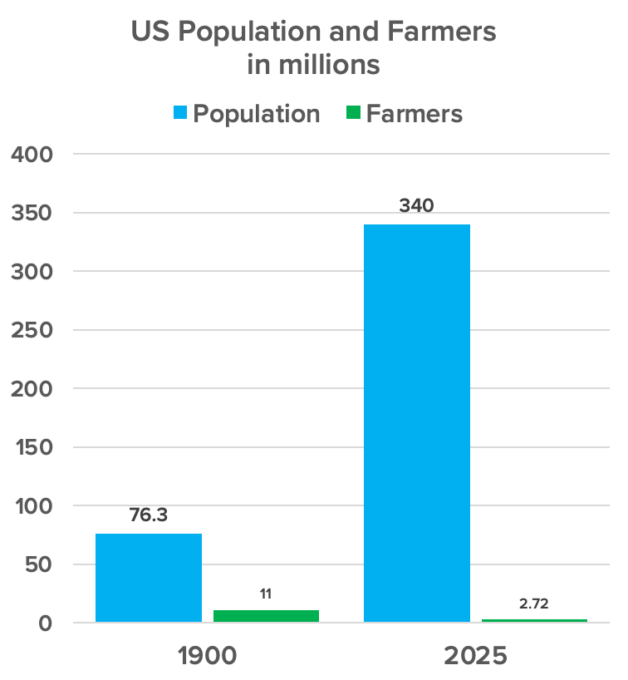

Current conversations about the baby bust are largely dominated by concerns over the economic and policy challenges it presents. As our population ages, we may face worker shortages, increased strain on social safety net programs, and economic stagnation. While these challenges are very important and demand our attention, it is equally crucial that we do not overlook the profound personal and existential consequences of this demographic shift.

Even if you believe that advances in automation, artificial intelligence, or other technological innovations will help mitigate the problems caused by a shrinking population, it is crucial to recognize that young people are an irreplaceable existential resource. They are the reasons we care about the future, providing us with the opportunity to achieve a level of social significance that transcends our brief mortal lives. No machine can replace the profound sense of meaning that raising the next generation of humans provides.

While human intelligence makes the creative, innovative, and industrious activities that lead to abundance possible, it is the meaning in life we derive from mattering to others that gives us the fundamental reason to pursue these activities in the first place.

This article was published at Flourishing Friday on 6/7/2024.