Summary: Halloween is a celebration of death and fear, but it also reveals how much safer and healthier life has become. This article shows how child mortality, especially from pedestrian accidents, has declined dramatically in recent decades. It also explores how other causes of death, such as disease and violence, have become less common thanks to human progress.

This Halloween, you might see your neighbors’ front yards decorated with faux tombstones and witness several children dressed as ghosts, skeletons, zombies, or other symbols of death. Thankfully, today’s trick-or-treaters can almost all expect to remain among the living until old age. But back when the holiday tradition of children going door-to-door in spooky costumes originated, death was often close at hand, and the young were particularly at risk.

Halloween’s origins are closely linked to concerns about death. The holiday arose out of All Souls’ Day, a Christian commemoration for the deceased falling on November 2 that is also simply called the Day of the Dead. In the Middle Ages, this observance was often fused with another church feast called All Saints’ Day or All Hallows’ Day on November 1. The night before, called All Hallows’ Eve—now shortened to Halloween—in parts of medieval Britain, children and people who were poor would visit their wealthier neighbors and receive “soul cakes,” round pastries with a cross shape on them. In exchange, they promised to pray for the cake-givers’ dead relatives. This was called “souling.”

In Ireland and Scotland, Halloween also incorporated some aspects of an old Celtic pagan tradition called Samhain, including bonfires and masquerades. Samhain was also associated with death and sometimes called the feast of the dead. Eventually the traditions of wearing masks and of going door-to-door for treats combined, and young people in Ireland and Scotland took part in a practice called “guising” that we now call trick-or-treating. Dressing as ghouls and other folkloric incarnations of death became popular.

In the 1800s, an influx of Irish immigrants is thought to have popularized this Halloween tradition in the United States. The phrase “trick-or-treating” dates to at least the 1920s, when Halloween pranks or tricks also became a popular pastime. But according to National Geographic, “Trick-or-treating became widespread in the U.S. after World War II, driven by the country’s suburbanization that allowed kids to safely travel door to door seeking candy from their neighbors.”

And just how safe today’s trick-or-treaters are, especially compared to the trick-or-treaters of years past, is underappreciated. Despite the occasional public panic about razor blades in candy, malicious tampering with Halloween treats is remarkably rare, especially given that upward of 70 percent of U.S. households hand out candy on Halloween each year.

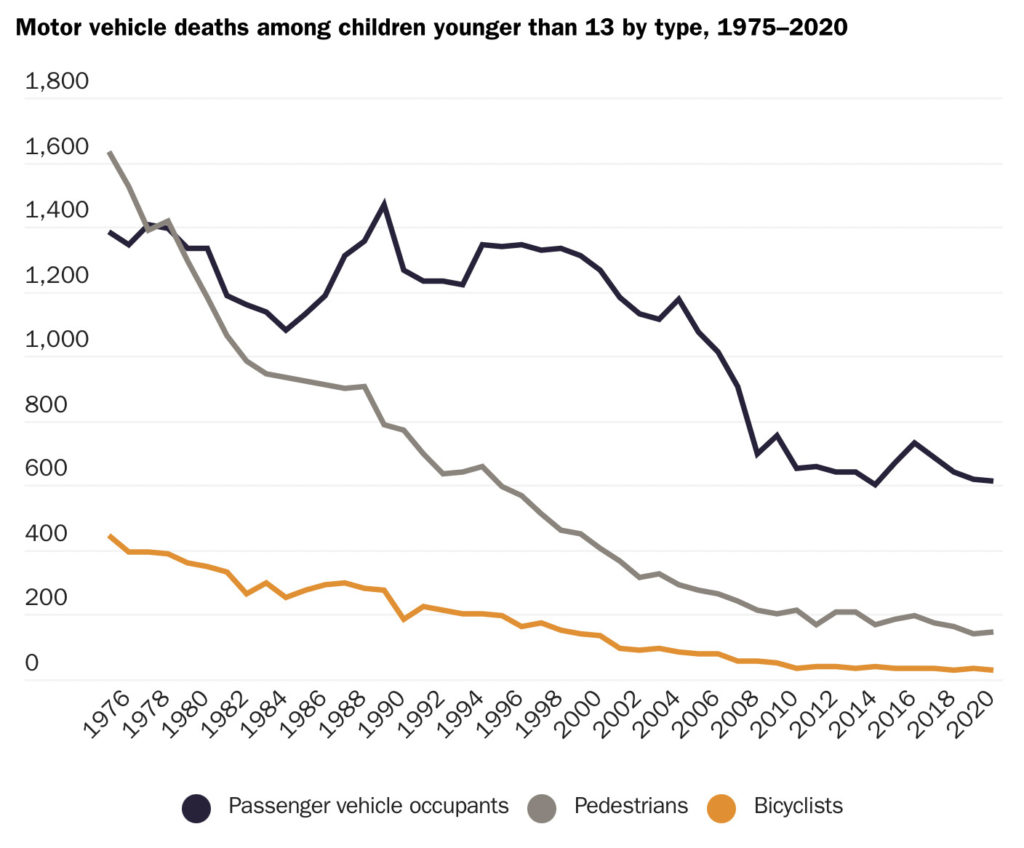

The biggest danger to today’s trick-or-treaters is simply crossing streets. But while Halloween is the deadliest night of the year for children being struck by cars, there is heartening news: annual child pedestrian deaths have declined dramatically. The number of pedestrian deaths among children aged 13 or younger fell from 1,632 in 1975 to 144 in 2020. The steep decline is even more impressive when one considers that it occurred as the total number of people and cars in the country has increased substantially.

Today’s children are thus safer as they venture out on Halloween than the last few generations of trick-or-treaters were. And, of course, when compared to the world of the very first children to celebrate Halloween, the modern age is by many measures less dangerous, especially for the young. In medieval England, when “souling” began, the typical life expectancy for ducal families was merely 24 years for men and 33 for women. While data from the era is sparse, among non-noble families in Ireland and Scotland, where “guising” began, living conditions and mortality rates may have been far worse.

It is estimated that between 30 and 50 percent of medieval children did not survive infancy, let alone childhood, with many dying from diseases that are easily preventable or treatable today. Given that context, the medieval preoccupation with death that helped give rise to traditions like Halloween is quite understandable. Life expectancy was lower for everyone, even adult royalty: the mean life expectancy of the kings of Scotland and England who reigned between the years 1000 and 1600 was 51 and 48 years, respectively. Before the discovery of the germ theory of disease, the wealthy, along with “physicians and their kids lived the same amount of time as everybody else,” according to Nobel laureate Angus Deaton.

In 1850, during the wave of Irish immigration to the United States that popularized Halloween, little progress had been made for the masses: white Americans could expect to live only 25.5 years—similar to what a medieval ducal family could expect. (And for African Americans, life expectancy was just 21.4 years.)

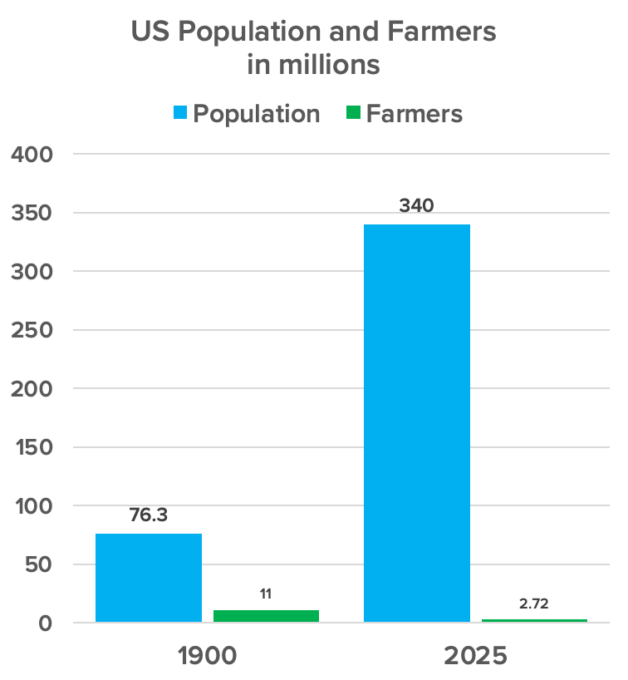

But the wealth explosion after the Industrial Revolution soon funded widespread progress in sanitation. That reduced the spread of diarrheal diseases, a major killer of infants—and one of the top causes of death in 1850—improving children’s survival odds and lengthening lifespans. By 1927, the year when the term “trick-or-treating” first appeared in print, there had been clear progress: U.S. life expectancy was 59 years for men and 62 years for women. The public was soon treated to some innovative new medical tricks: the following year, antibiotics were discovered, and the ensuing decades saw the introduction of several new vaccines.

In 2021, U.S. life expectancy was 79.1 years for women and 73 years for men. That’s slightly down from recent years but still decades longer than life expectancy for the aforementioned medieval kings who ruled during Halloween’s origins. Life expectancy has risen for all age groups, but especially for children, thanks to incremental progress in everything from infant care to better car-seat design.

So as you enjoy the spooky festivities this Halloween, take a moment to appreciate that today’s trick-or-treaters inhabit a world that is in many ways less frightening than when Halloween originated.