Summary: Work has changed dramatically over time, shifting significantly from physical to mental labor. Today, office jobs demand far less physical energy and carry far lower risks of injury or death compared to physically demanding trades. This transition shows how progress has allowed us to create more value with less strain on our bodies—and with far greater safety than workers of the past could have imagined.

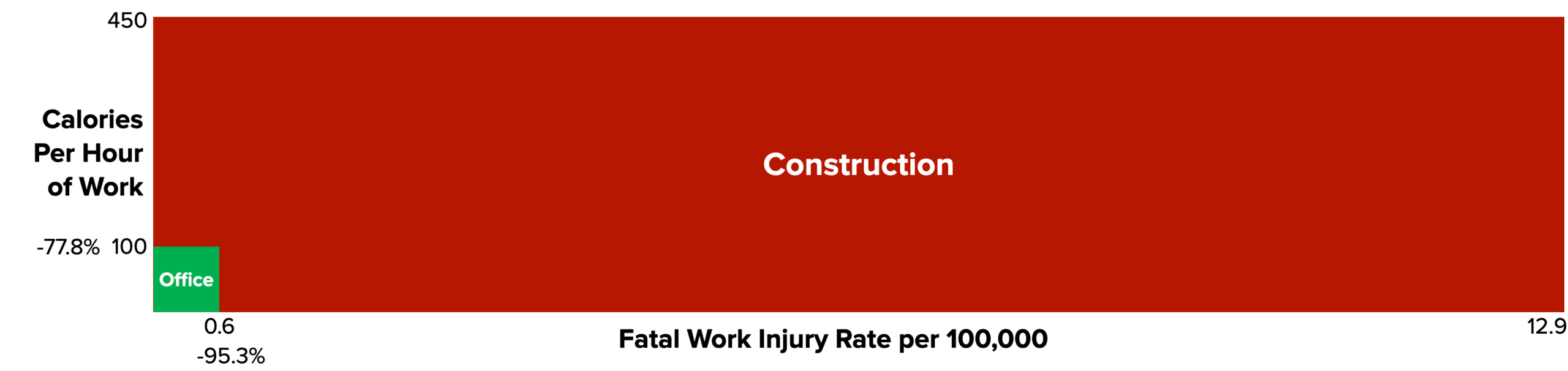

Economist George Gilder points out that using blue-collar hourly wage rates to calculate time prices underestimates the gains we’re enjoying in an economy that’s no longer driven by muscle but by mind. Knowledge workers earn more in an hour, consume fewer calories, and risk far less death or injury than other workers. In other words, they do far more with far less. This is the true compounding of progress—and we can see it mapped on a single chart.

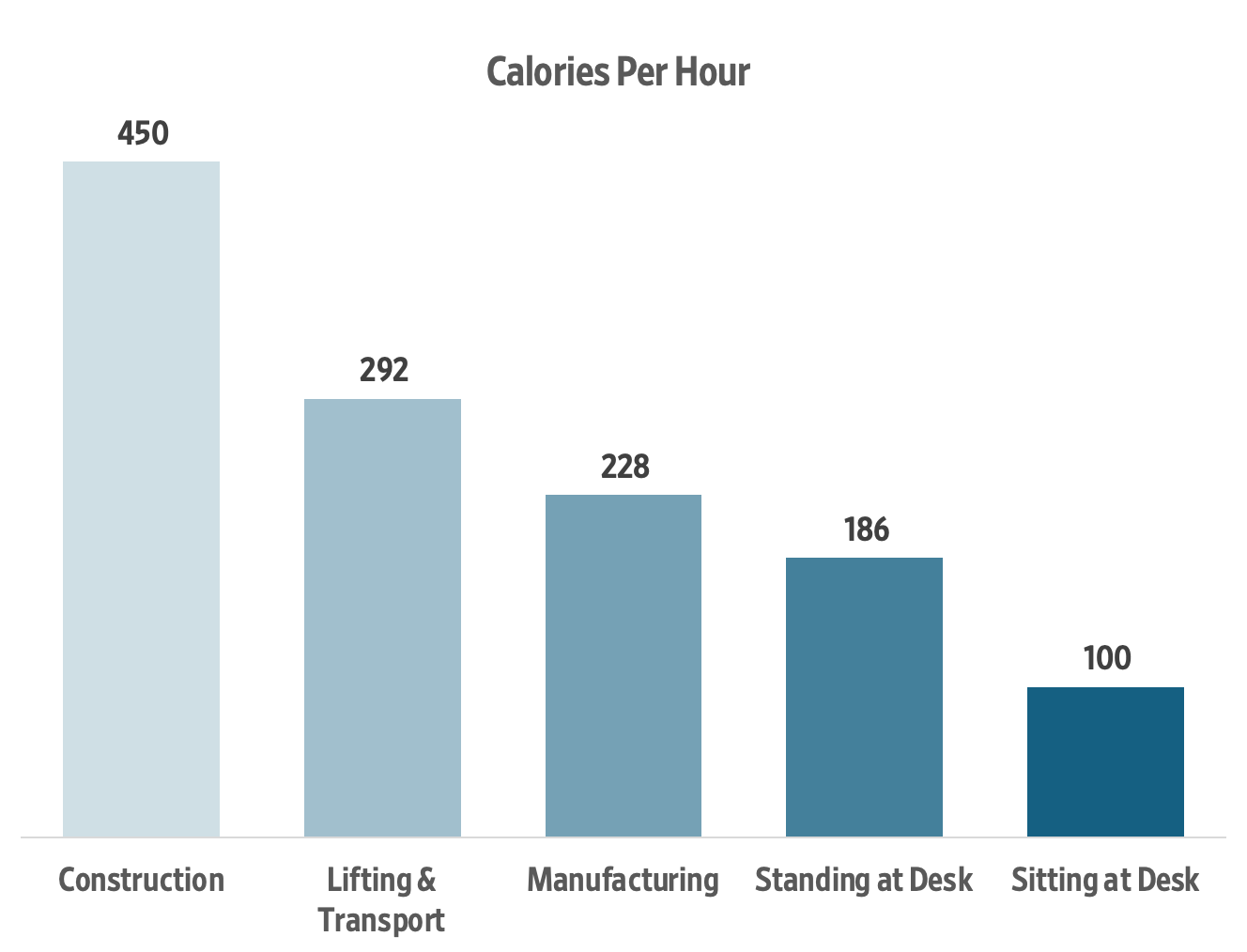

Calories Per Hour of Work

I asked several AI models about the number of calories per hour that different kinds of work require and this is what I got:

The energy demands of physical work versus knowledge work reveals a dramatic difference in caloric expenditure. Workers in physically demanding jobs burn significantly more calories than do their office counterparts:

High-energy physical work:

- Construction tasks such as masonry or hanging sheetrock: 400–500 calories per hour (equivalent to running or high-intensity aerobics)

- Heavy lifting and transport: 285–300 calories per hour for a 170-pound worker

Moderate physical work:

- Manufacturing: 228 calories per hour (men), 180 calories per hour (women)

Office work:

- Standing desk: 186 calories per hour for a 170-pound person

- Sitting desk work: 100 calories per hour

As we transition from working with atoms to working with knowledge our bodies require a lot less energy to perform that work. Moving from construction work to sitting at a desk in an office requires 77.8 percent fewer calories per hour. Put another way, the calories needed to fuel one construction worker can power 4.5 office workers. The result is an economic system that creates more value with less resource consumption.

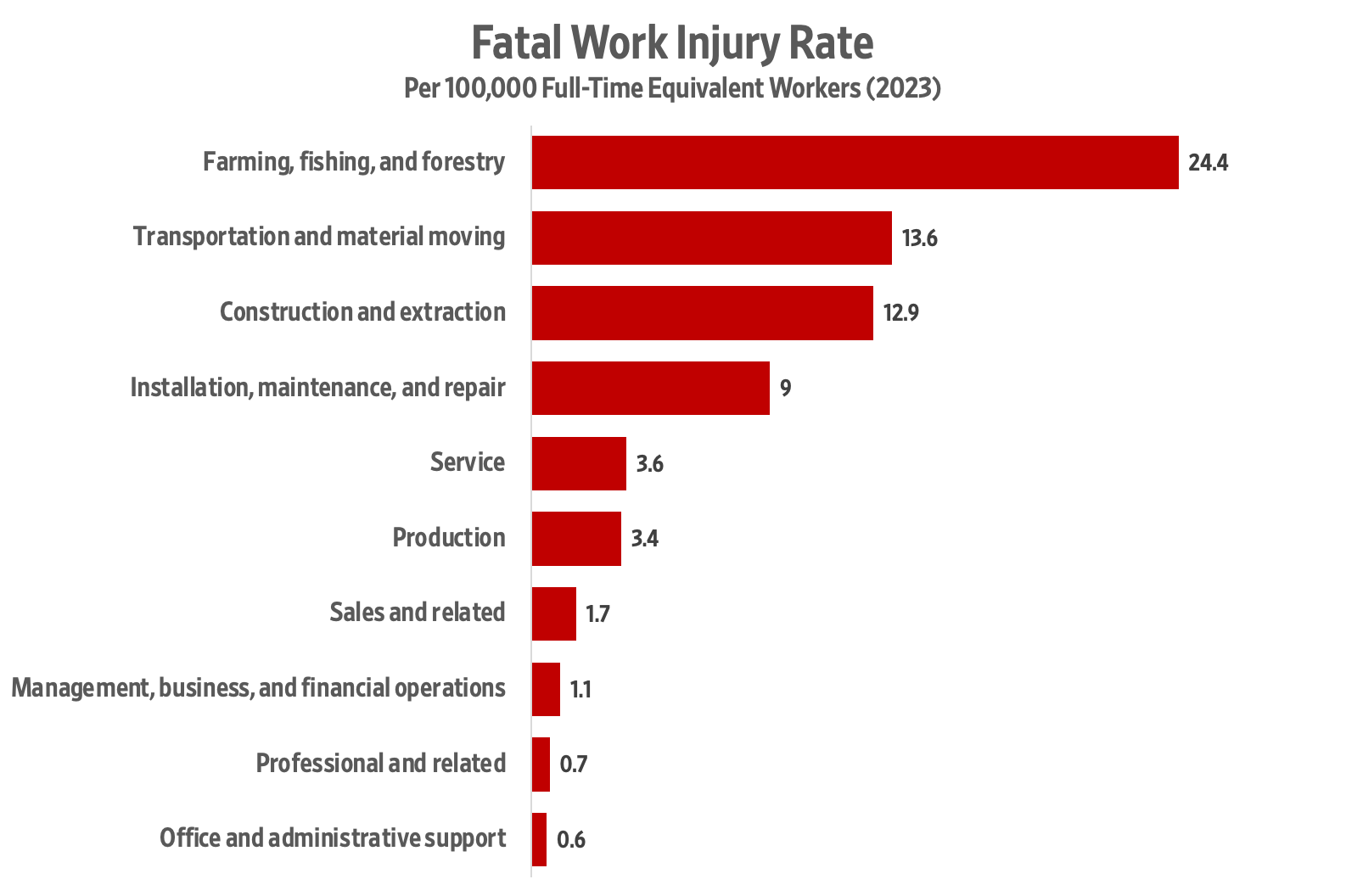

Fatal work injury rate

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports on fatalities on the job:

Farming, fishing, and forestry are the most dangerous professions at 24.4 fatal injuries, with transportation and material moving at 13.6, and construction and extraction at 12.9. Office and administrative support are the least risky professions at 0.6. Farmers, fishermen, and loggers are more than 40 times likely than an office worker to be killed on the job. Moving from construction work to sitting at a desk in an office reduces the risk of a work fatality by 95.3 percent. Adjusted for population size, construction workers experience a work-related fatality rate more than 21 times higher than that of office workers.

And it was much worse in the past—something that we tend to forget when looking at present statistics. In 1900, deaths in the mining and oil extractions fields (lumped under mining) was estimated at 333 per 100,000 workers and remained that high through the 1920s. We can hardly comprehend just how good we’ve got it now.

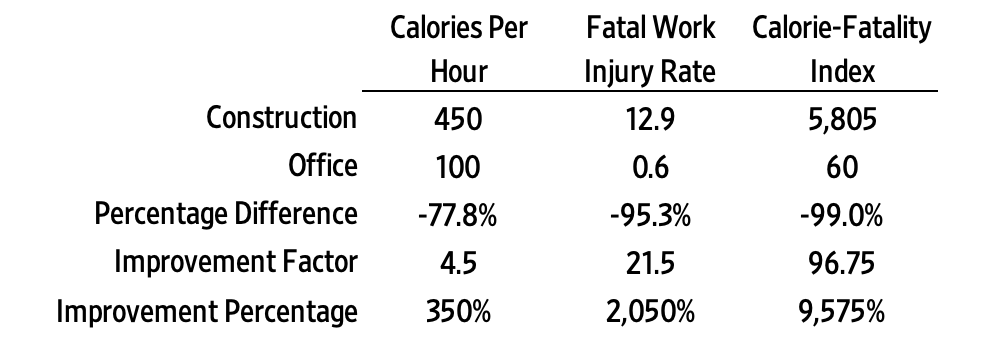

Calorie-fatality index

If we combine these two factors into a calorie-fatality index and compare the construction and office industries, we note that office work is 99 percent lower than construction work on the index. Moving from blue-collar construction work to an office job indicates an overall improvement factor of 96.75 (or 9,575 percent) on the calorie-fatality index.

Find more of Gale’s work at his Substack, Gale Winds.