Today marks the third installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

Our third Center of Progress is Mohenjo-Daro, a city in today’s Pakistan that pioneered new standards of urban sanitation. The city is thought to have been constructed circa 2500 BC, although the site has been inhabited since around 3500 BC. Mohenjo-Daro was the largest urban center of the ancient Indus Valley civilization, covering nearly 500 acres, and one of the world’s earliest major cities.

The people of the Indus Valley civilization invented new water supply and sanitation devices that were the first of their kind. They included piping and a complex sewage system. Tunnels under Mohenjo-Daro carried the city’s waste to a nearby estuary. Almost all of the city’s houses had indoor baths and latrines with drains, and the city also showed its dedication to cleanliness with a large public bathhouse used for ritual bathing. National Geographic has opined that their civilization enjoyed the “ancient world’s best plumbing,” in some ways surpassing even the plumbing system that the Roman civilization would later create.

Ever since humanity gave up hunting and gathering to live in permanent settlements, our species has faced health challenges related to hygiene and the proper disposal of waste. Since the advent of cities, humanity has been vulnerable to rapidly spreading illnesses, because disease propagates more easily in concentrated populations. That is particularly true without adequate sanitation, and water-borne illnesses—such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid, and various gastrointestinal diseases—were once a common cause of death.

Advances in sanitation have allowed people to live near one another in cities with less risk to their health than in the past. In particular, safe disposal of effluent to spare the water supply from contamination has proved to be a truly game-changing innovation. It has been argued that plumbers are the unsung heroes of civilization.

Today, Mohenjo-Daro is a striking archaeological site in the Sindh province of Pakistan. The site’s name means “Mound of the Dead” in Sindhi. Only part of the ancient city has been excavated and much of it remains hidden. Mohenjo-Daro has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Located on the right bank of the Indus River, Mohenjo-Daro is the most impressive of the ruined cities remaining from the Indus Valley Civilization. Mohenjo-Daro’s surviving structures are made of bricks fashioned from red sand, clay, and stones, lending the ruins a ruddy hue.

The Indus Valley civilization arose in the floodplains of the Indus and Sarasvati rivers in what is now northwest India and Pakistan, around 5000 years ago. The rivers flooded twice a year in a predictable manner, making the land fertile and allowing the Indus people to farm everything from cotton to dates to support their growing population.

Their prosperity also flowed from conflict avoidance and from their vast trade networks. They established one of the first long-distance trade relationships in the world by exchanging goods with the Mesopotamians located nearly two thousand miles to the west, as early as 3000 BC. Indus exports included spices such as clove heads, luxury goods like carnelian beads artfully etched with acid, and possibly even livestock such as water buffaloes. Their imports from the Mesopotamians included textiles and various artistic motifs and legends—including aspects of the legend that would come to be known as the Epic of Gilgamesh. The Indus people also had what is thought to be a written language, now called the Indus Script, which has yet to be deciphered by scholars.

If you could have visited Mohenjo-Daro in its heyday, you would have seen an orderly city of dense, multistoried homes with flat roofs fashioned out of uniformly sized bricks, standing along a grid of perpendicular streets. The grander houses had up to twelve rooms. You would have seen people gathering water, in decorated pottery jugs, from the numerous public wells and chatting, perhaps discussing art. Archeological evidence suggests that Mohenjo-Daro’s residents enjoyed art forms ranging from metal sculpture to dance. You may have observed children playing games, including games with dice, which many historians believe that the Indus people invented.

The city’s population may have peaked at around 40,000 people, similar to the population of Annapolis, Maryland, today. The men probably wore a cloth around their waist, perhaps gathered in a way that resembles modern dhoti pants, while the women wore longer skirts or robes. Wealthy people of both sexes wore jewelry with ivory, lapis, carnelian, and gold beads, as well as elaborate hairstyles and headdresses.

Walking through the city, you would have observed that Mohenjo-Daro had no grand temples, palaces, monuments or royal tombs. The society of Mohenjo-Daro seems to have been far less hierarchical than the cities of the Mesopotamians with whom the former traded. The people in Mohenjo-Daro may have had no king or, if they had one, he had only little authority. The lack of any royal structures certainly suggests the absence of a powerful ruler, although it remains unknown what kind of system governed the city.

Instead of a palace, the largest structure in the city was an immense, elevated public bathhouse. The Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro measured almost 900 square feet, with a maximum depth of around 8 feet. It was constructed of fine brickwork, with a pool floor made of three layers: sawed brick set in gypsum mortar, then bitumen sealer, followed by another layer of sawed brick and gypsum mortar.

The status of the bathhouse as the city’s biggest and most prominent structure suggests that the people of Mohenjo-Daro highly valued cleanliness. Their entire ideology may have been based on cleanliness, according to historian Gregory Possehl of the University of Pennsylvania.

The bathhouse may have been a sacred place, and scholars believe that it was likely used for ritual bathing. The people did not need to use the bathhouse for everyday washing, because the houses of the city each had what was then a remarkable, groundbreaking feature: practically every home in the city, from the largest to the humblest, had a washroom.

These rooms were typically small, and square or rectangular in shape. In each washroom, the brick pavement floor was carefully built to slope toward a corner containing a simple latrine and drain, as well as a drained washing area. The slanted floors helped to ensure proper drainage, and the bricks were set tightly together to prevent leaking. Around each drain-hole the bricks were so meticulously rubbed down and fitted together that the joints were nearly invisible. In some cases, the bricks were overlaid on a bed of pottery debris to further bolster the floor’s resistance to leaks.

Homes with washrooms on upper floors were fitted with vertical terracotta pipes that carried effluent down to the street-level. The pipes of fired clay were joined together with tar to make them watertight. The Indus were the first people to have indoor plumbing, perhaps as early as 3000 BC. The pipes were positioned so that wastewater flowed down into the drain ditches that ran along every avenue in the city, and then into underground tunnels. Thanks to the invention of drain ditches, the cleanliness of the city’s streets was remarkable for the ancient world.

As the city’s population grew and the amount of waste it processed increased, the people kept their drain ditches functional by raising the brick walls alongside the former—to prevent effluent overflow into the streets. Archeological evidence suggests that the walls grew gradually in size to meet the city’s needs. The ditches and connected underground sewage tunnels carried waste away from the city, protecting its well-water supply from contamination.

Just like modern washrooms, the washrooms of Mohenjo-Daro were used for multiple personal hygiene activities, including bathing. Surviving artifacts suggest that the Indus poured pottery jugs of water over themselves to shower, and utilized clay scrapers similar to Greco-Roman strigils to cleanse themselves. In these rooms they also used pottery rasp tools to remove cuticles and shape their nails. Some washroom ruins contain what may be oil residue, suggesting that the washroom was also where Mohenjo-Daro’s residents moisturized their skin with oils.

Some traditions appear to be timeless. For example, evidence suggests that Mohenjo-Daro’s children played with bath toys just like today’s children. Instead of rubber ducks and plastic boats, their toy figurines were made of pottery. “[T]o judge from the number of pottery models that have been found in the drains, it would seem that the childish habit of taking play-things into the bath has persisted for thousands of years,” according to the British archeologist Ernest Mackay, who led the excavation of Mohenjo-Daro in the 1920s and 1930s.

Children were arguably the greatest beneficiaries of Mohenjo-Daro’s dedication to hygiene, although the city’s washrooms and sewage system were essential to the health of all of its people. While it can be hard to remember for those of us lucky enough to be able to take modern sanitation for granted, standards of hygiene throughout most of human history have been appalling. Associated illnesses were responsible for high rates of mortality, especially among children.

Mohenjo-Daro’s advanced plumbing serves as a reminder that progress is not steady or linear. Many people who lived thousands of years later coped with conditions far less hygienic than those enjoyed by Mohenjo-Daro’s people in the 3rd millennium BC.

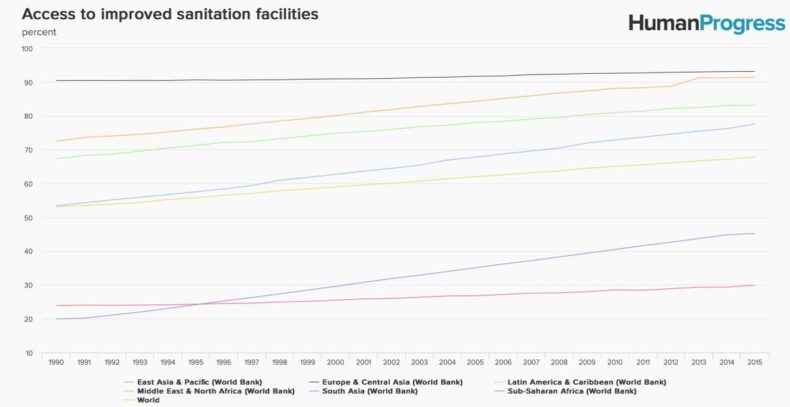

It was not until the 19th century that urban sanitation became widespread. Those advances, along with the discovery of the germ theory of disease, are the primary reasons for the dramatic rise in human life expectancy, according to Nobel Prize–winning economist Angus Deaton. While more people now enjoy proper sanitation than at any other time in history, even today, in poor areas of the world, far too many people contend with inadequate sanitation and accompanying diseases.

Mohenjo-Daro is thought to have been gradually abandoned almost four thousand years ago, when the Indus river shifted its course and farmers could no longer rely upon it to irrigate their crops. Today, Mohenjo-Daro is best-known as the largest remnant of the enigmatic Indus Valley civilization. Because the Indus people’s writing system is currently unreadable, many aspects of that civilization remain a mystery. The religion and seemingly kingless government system of Mohenjo-Daro are unknown, as are the reasons for the Indus Valley civilization’s ultimate demise.

For developing plumbing and wastewater management, Mohenjo-Daro has earned its place as our third Center of Progress. Without washrooms and sewage systems, our lives would be far shorter and less hygienic.