This last U.S. election was unlike any other in contemporary history in one important regard: some no longer felt that the country would see a peaceful transition of power from the incumbent to the president-elect. Many feared that a Trump reelection could prompt mass riots and looting, leading numerous businesses in urban areas to board up their glass doors and windows in preparation for unrest. And even now that Biden has secured a victory—albeit one that may face vote recounts in some states—some commentators worry that some Trump supporters could refuse to accept the election’s results.

While concerns about civil unrest are worth taking seriously, and any purported election anomalies should be fully investigated, we should also take heart in the fact that peaceful transitions of power—once rare—have become more frequent in much of the world. Still, peaceful power handovers are far from the “default.” According to an analysis by The Economist, in the past hundred years, only about half of the world’s countries have managed even a single power-transfer free of coups, civil wars, or constitutional crises. The good news is that once a country does manage to secure a peaceful change of government, the practice tends to become entrenched over time and creates positive momentum for continued peaceful power-transitions.

Consider a long-run historical perspective. Throughout most of humanity’s existence, authority typically changed hands through force. Kings often assassinated their predecessors, even killing close family members of the deposed monarchs, or defeated the prior ruler in battle. Consider ancient Rome during what has come to be known as the Crisis of the Third Century, a period of turmoil and particularly fraught political transitions. Take a moment to think of the fates of the fourteen emperors between Maximinus (ruled 235–238 CE) and Aurelian (ruled 270–275 CE).

After Maximinus’ assassination, the co-rulers Pupienus and Balbinus reigned for three months before their own Praetorian guards murdered them. The next emperor, Gordian III, either died in battle or by treason—the record is unclear. The emperor after that, Philip the Arab, was killed by Decius, who then ruled until he and his co-ruler son Herennius Etruscus both died fighting the Goths. Decius’ other son Hostilian briefly led the empire until he died either from the plague or murder—the record is again unclear. The next emperor, Trebonianus Gallus, was killed by his own soldiers. Three months into his reign, the subsequent emperor Aemilianus was also killed by his own soldiers. Notice a pattern?

The next emperor, Valerian, was taken prisoner by the Sassanids and killed. In some versions of the story, his captors skinned him alive, while in others, they executed him by forcing him to drink molten gold. His son Gallienus eventually fell victim to a murder conspiracy. His successor Claudius Gothicus died of the plague after about a year. His brother Quintillus reigned for a few months before meeting an untimely end. Conflicting reports suggest that he either committed suicide, fell prey to assassination by political rivals, or his own soldiers killed him. The next emperor, Aurelian, was also ultimately murdered by his own people.

The Third Century Crisis serves as an extreme example of one abrupt, often violent, power-transition after another over a relatively short period. But the fact remains that violent government transitions were once ordinary.

The trend of peaceful transitions of power becoming more common throughout the world—although they are still, unfortunately, not the norm everywhere—is related to the global rise of liberal democracy. That system of government is much better at producing peaceful regime changes than authoritarian systems. Among other benefits, the electoral process provides a means for internal opponents of the current regime to seize power without bloodshed. By replacing murder plots with campaign strategies, and assassins with political consultants, a functioning liberal democracy substitutes peaceful persuasion for lethal force.

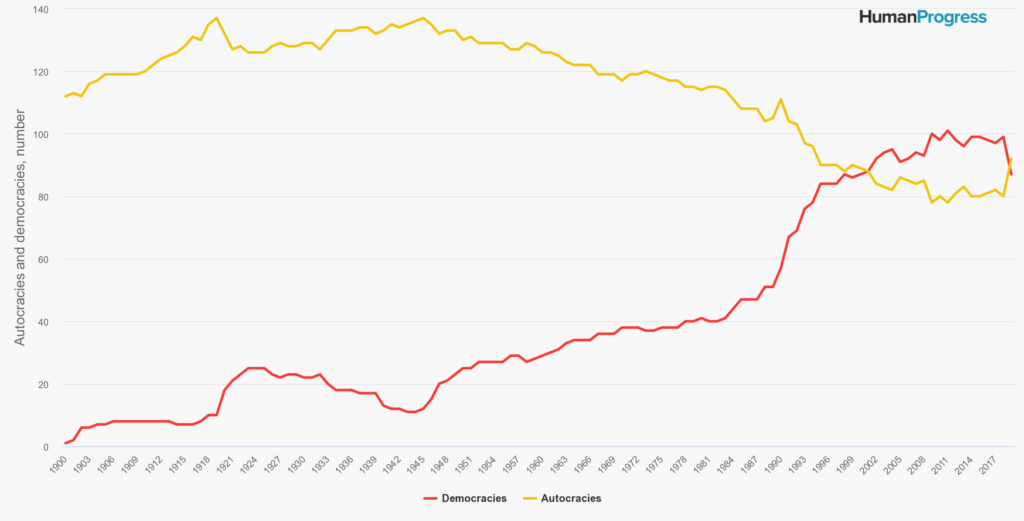

Unfortunately, the long-term trend of democratization has recently reversed—and for the first time since the dawn of the new millennium, autocracies again outnumber liberal democracies. The Varieties of Democracy Institute at the University of Gothenberg in Sweden now classifies Honduras, Hungary, Nicaragua, Niger, the Philippines, Serbia, Thailand, Turkey, Venezuela, and several other former democracies as autocracies, when defined as scoring less than 0.5 on the Electoral Democracy Index (scale 0-1). In some cases, such as that of Hungary, the Institute reports that a rise in an illiberal form of populism is behind the change.

Peaceful government transitions via the ballot box should never be taken for granted. Globally speaking, they are far from the norm, even in modern history. Even once a country establishes a tradition of peaceful power-transfers, there are no guarantees that the tradition will continue. In his presidential Farewell Address that precipitated the first peaceful transition of power in the young American republic, George Washington spoke about the dangers of politics revolving around intense warring factions. He described the spirit of factionalism as “a fire not to be quenched,” and warned that it “demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.”

It is no simple matter for a diverse democratic community to sustain itself despite inevitable internal conflicts. As the United States deals with the aftermath of the election, its citizens should keep the following in mind. A tradition of peaceful power transitions must be treasured, and protected through conscious effort, or, as Washington put it, vigilance.

This first appeared in The National Interest.