In his 1968 book The Population Bomb, Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich warned that overpopulation and overconsumption would result in the exhaustion of resources and a global catastrophe. To understand whether that is likely to happen, it is important to recognize that resources are not finite in the same way that a slice of pizza is finite. That’s because the totality of our resources is neither known nor fixed.

In a competitive economy, humanity’s knowledge about the value and availability of something tends to be reflected in its price. If prices fall, resources can be deemed to have become more abundant relative to demand. If prices increase, they can be deemed to have become less abundant, again relative to demand. Higher prices also create incentives for innovation, including discoveries of new deposits, greater efficiency of use, and the development of substitutes.

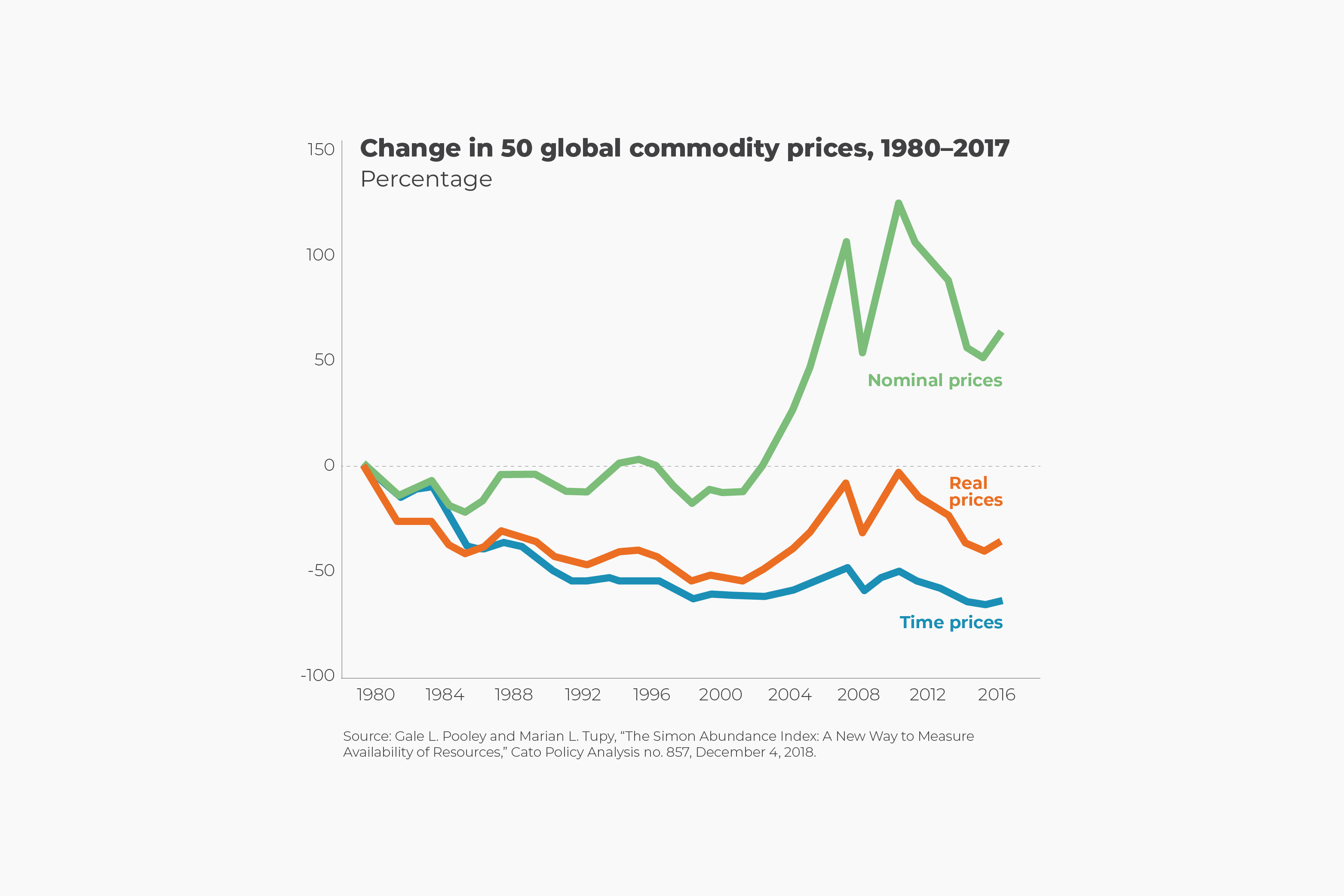

In a recent paper, one of us looked at prices for 50 foundational commodities covering energy, food, materials, and metals. The data were collected by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund between 1980 and 2017. The paper found that the nominal prices of 9 commodities fell, whereas the nominal prices of 41 commodities increased. The average nominal price of 50 commodities rose by 62.7 percent. Adjusted for inflation, however, 43 commodities declined in price, 2 remained equally valuable, and only 5 commodities increased in price. On average, the real price of 50 commodities fell by 36.3 percent.

Between 1980 and 2017, the inflation adjusted global hourly income per person also grew by 80.1 percent. Therefore, for the amount of work required, commodities became 64.7 percent cheaper. Put differently, commodities that took 60 minutes of work to buy in 1980 took only 21 minutes of work to buy in 2017. All in all, resources are not being depleted in the way that Ehrlich feared they would—as witnessed by the fact that humanity has not yet run out of a single supposedly nonrenewable resource. In fact, resources tend to become more abundant over time relative to the demand for them.