Nearly 90 percent of the world’s population in 1820 was illiterate. Today almost 90 percent can read. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) broadly defines literacy as “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts.” A common benchmark of literacy, to give just one example, is the ability to read a newspaper.

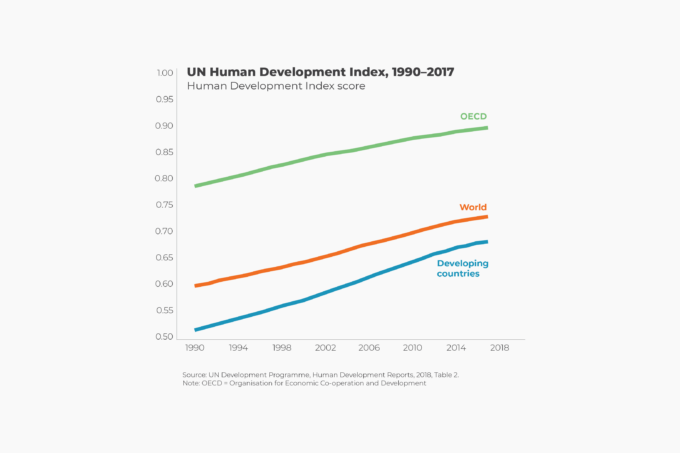

Being able to read and write is associated with reduced poverty rates, decreased mortality rates, greater gender equality, lower fertility rates, and increased political awareness and participation. According to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report, if all students in low-income countries left school with elementary reading skills, 171 million people could be lifted out of poverty.

“Being able to read and write is associated with reduced poverty rates, decreased mortality rates, greater gender equality, lower fertility rates, and increased political awareness and participation.”

Global progress toward universal literacy over the past two centuries has been uneven. By 1940, more than 90 percent of the people living in the United States, Canada, Australia, Western Europe, and Eastern Europe were literate. In contrast, only about 42 percent of the populations of Latin America and East Asia could read. At that time, the rates of literacy in the Middle East and North Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa were about 15 percent, 11 percent, and 10 percent, respectively. Given these regional disparities, the global literacy rate in 1940 was still below 50 percent.

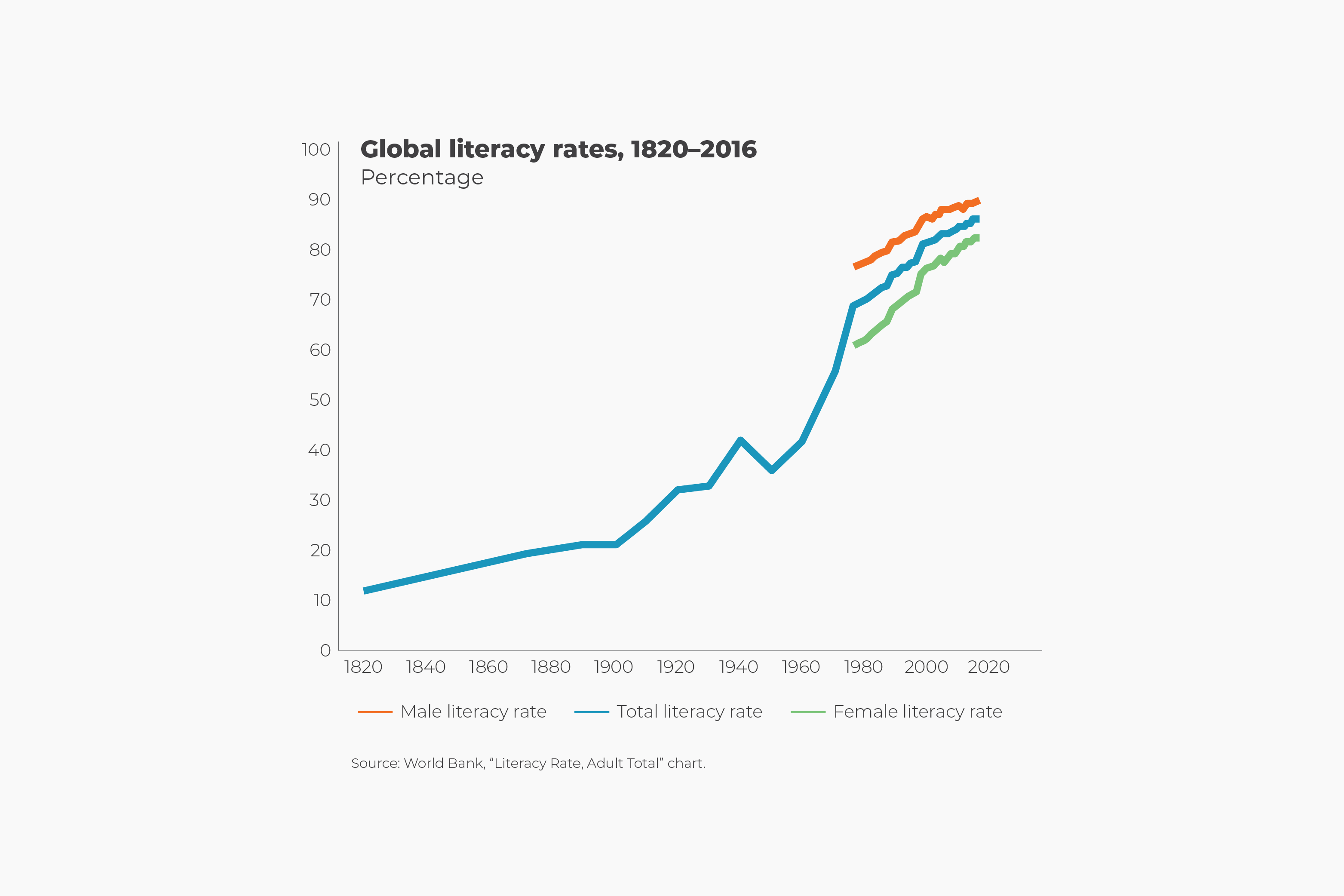

According to the World Bank, the global literacy rate among men ages 15 and older was about 77 percent in 1970, rising to nearly 90 percent by 2016. Among women, that number rose from 61 percent to 83 percent over the same period. In 2016, nearly 90 percent of women between the ages of 15 and 24 were literate. That number was almost 93 percent among men of the same age. Clearly, literacy gaps between rich and poor countries, and men and women, are closing.