Read the full transcript or listen to the full podcast episode with Chelsea Follett and Stephen Barrows here.

The world population recently reached 8 billion people, sparking considerable debate about the consequences of population growth size. These concerns, of course, aren’t new. Can you walk us through the history of concerns about overpopulation?

Those concerns are traceable back to Thomas Robert Malthus, who lived in the UK in the late 18th century. Malthus observed that the population grew at a geometric rate, while the resources of the Earth, particularly food, only grew at an arithmetic rate. As a result, he argued that there is a limit to population that is enforced by famine and plague.

But Malthus was shortsighted. He saw poverty and a lack of resources, but he didn’t see the other side of the ledger, which is what humans can do to overcome population pressures. However, his concerns never went away.

Could you walk through some of the reactions from economists to these Malthusian ideas? How were they received?

Not all economists are pro-population growth, but generally speaking, they see a different dimension to human activity than what you might find from environmentalists and other experts in different fields.

Individuals like Jean-Baptiste Say and Frederick Bastiat began to interact with Malthus’s work and acknowledged some truths behind what he was saying. For example, as you employ agricultural land for crop production, you use the most productive land first, and then as you expand agricultural production, you use the less fertile land, and yields decline. But at the same time, these economists emphasize that human ingenuity is not static. Individuals adapt to their circumstances and find new ways to make the Earth’s resources more productive. We adapt to our circumstances in ways that you don’t see elsewhere in the animal kingdom.

In the late 19th century, Böhm-Bawerk and Friedrich Wieser bring up other factors. Böhm-Bawerk argued that the interest rate regulates prices through time and helps us accommodate some of the pressures from population growth. Similarly, Friedrich Wieser pointed out that in his own day, there was a significant increase in crop yields due to technology.

Economists like Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, and Murray Rothbard emphasize the division of labor. Individuals have unique talents; if they specialize in what they do best, it benefits the whole population and helps us overcome pressures on the Earth’s resources. Murray Rothbard also pointed out that the idea of overpopulation presupposes an optimum population. And so, the question becomes, “what is the optimum population? And is it fixed?” And the answer is no because the environment is changing all the time, along with individual knowledge and technology. So, the so-called optimum population is also constantly changing, meaning that over or underpopulation is just a theoretical concept, not a concrete reality.

So, economists have been pushing back on this idea in various ways. One of the more recent prominent examples is the bet between the late University of Maryland economist Julian Simon and Paul Ehrlich. Could you talk to our listeners about that?

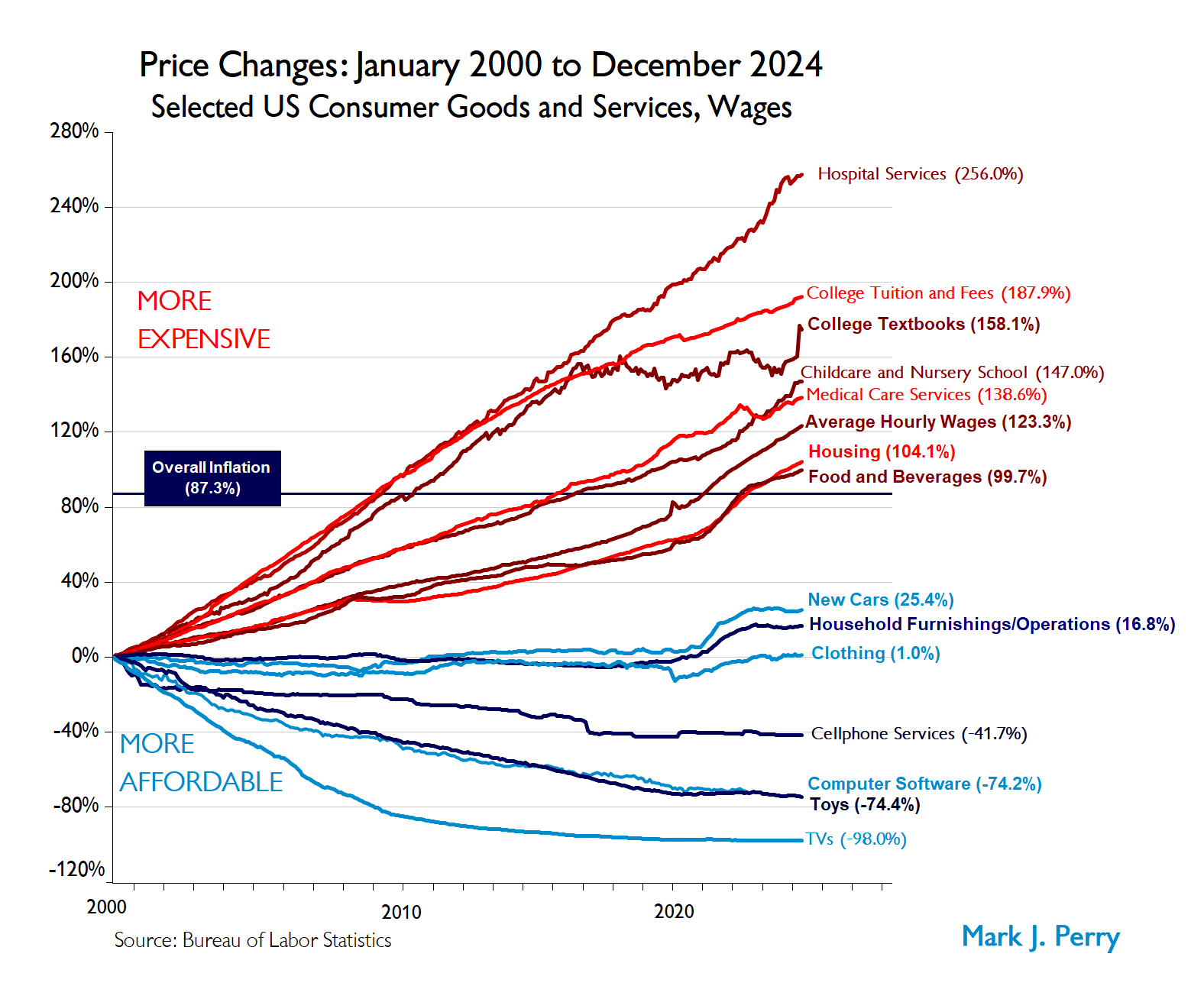

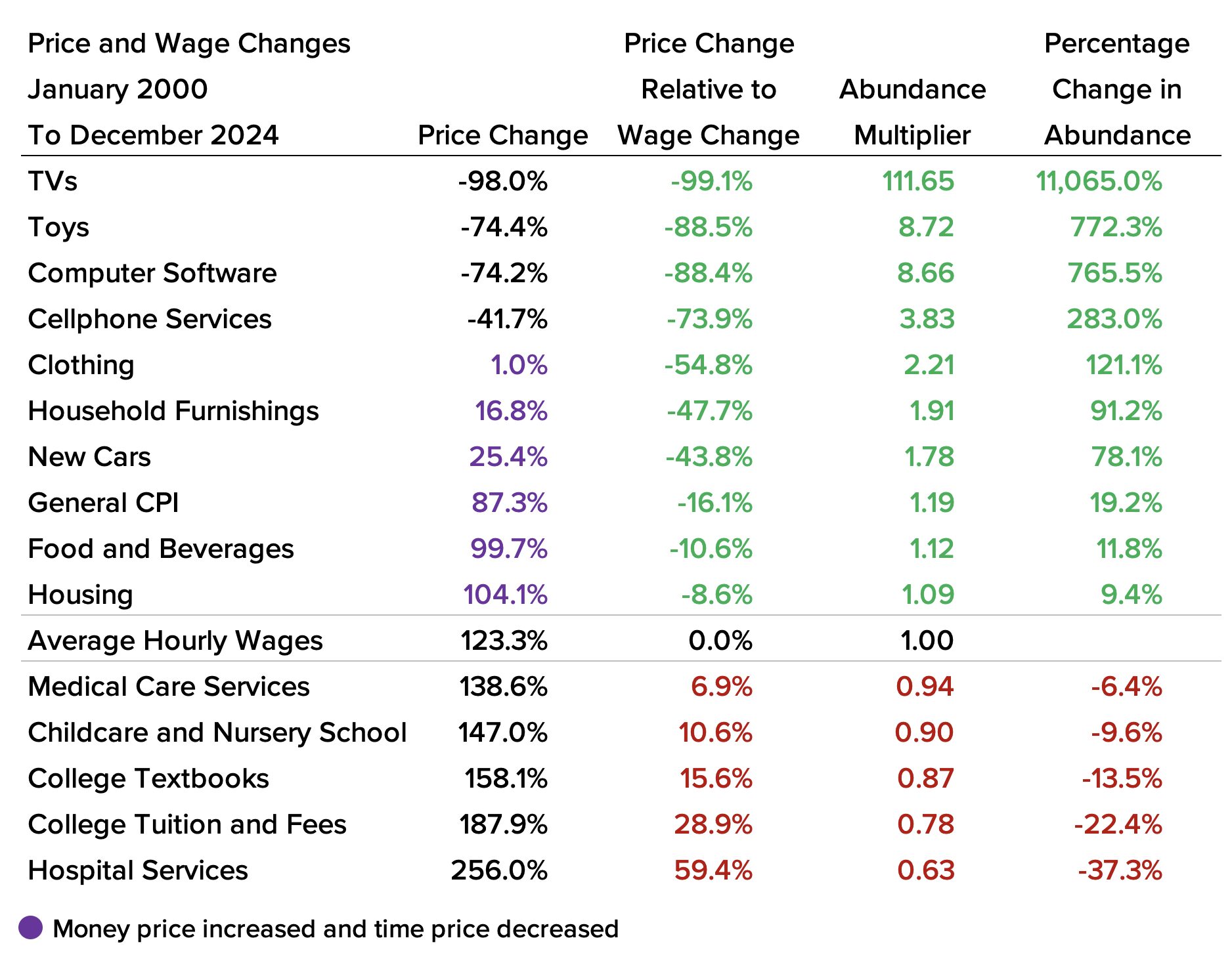

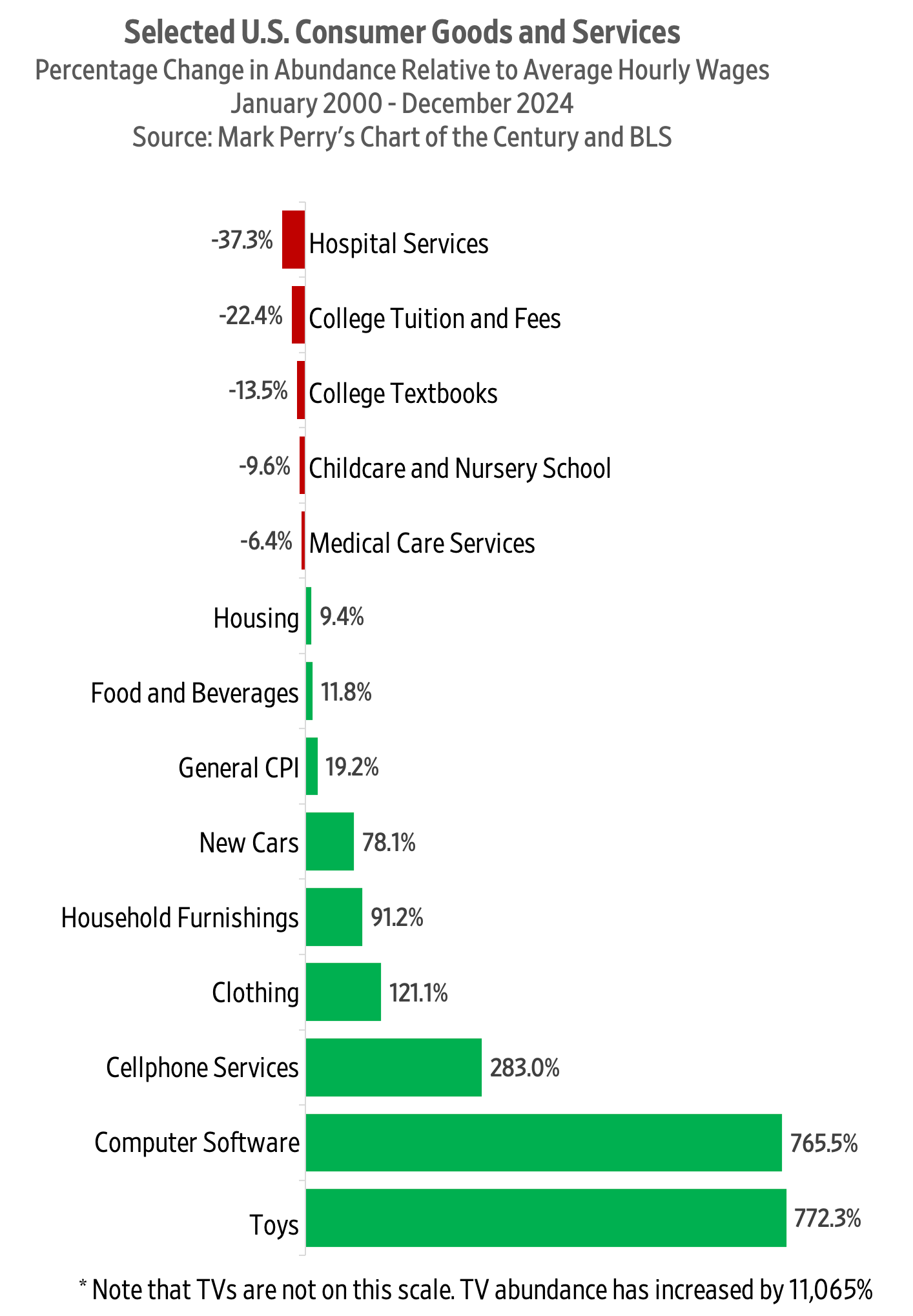

Ehrlich was an entomologist who wrote The Population Bomb in 1968, which made all sorts of apocalyptic predictions about mass famine and so forth. At around the same time, Julian Simon was investigating population and initially agreed that population growth was detrimental to the Earth’s resources. However, after he examined the data, he saw that his concerns were misplaced and that, in fact, population growth is associated with economic improvement.

They began debating back and forth, and eventually, Julian Simon proposed a bet. They created a price index of five metals and watched it for ten years. Simon bet that the price index would fall, and Ehrlich said that it would rise. Paul Ehrlich lost the bet.

Why did he lose? What is the relationship between population and prosperity?

When people think of population growth, I think too often they think in terms of stomachs and not minds. Humans have needs; we need to consume to survive, and it’s true that the Earth is finite in terms of its concrete materials. But the human mind is infinite. There’s no limit to ideas and ingenuity; the human mind can get effectively infinite value out of fixed resources. Think about the smartphone and all the objects that we no longer produce because we all have them in our pockets.

In short, the mind trumps the stomach.

Today, birth rates are falling below the replacement rate in advanced economies. If all the countries in the world end up on that same trajectory, we could end up even with global sub-replacement fertility. What do you think about the potential effects of global falling birth rates and population decline?

There’s a great book called The Great Demographic Reversal, which points out that not only does population growth matter, but the shape of the global population matters, whether your population skews young or old. As the population ages, there are fewer workers producing and a large older demographic still consuming, which can cause prices to rise.

Some of the challenges of a shrinking population will be addressed through innovation. In Japan, for example, they use exoskeletons to help people work into very old age, even in manual labor jobs. However, as a general rule, low fertility rates lead to a relative lack of new ideas. You need people to solve problems, and as you have fewer people to tap from, you don’t have the kind of ingenuity and division of labor that you had before. Innovativeness also tends to decline as you get older. That’s just the natural cycle of humanity. So, hopefully, we won’t see global population decline. I don’t think we’ve ever seen gradual global population decline in history. We’ve seen shocks to population, plagues, et cetera, but we’ve never seen a steady decline across the globe, and nobody really knows what that entails.