Summary: A seismic shift occurred in the Netherlands in 2023 when the Dutch BBB party, born out of farmer discontent, challenged the previous political landscape with electoral victory. The movement, ignited by frustrations over environmental regulations, signals a broader global trend of mounting tensions between agricultural freedom and environmental regulation. There are key misconceptions revealed by this debate about the balance between human enrichment and environmental conservation.

This article was published at Libertarianism.org on 1/23/2024.

The conflict between farmers and environmentalists has been simmering for years, and in 2023 it finally boiled over into electoral politics. The Dutch BBB (BoerburgerBeweging) or Farmer-Citizen Movement began in 2019 as a series of protests against environmental regulations that had a disproportionate impact on farmers. In March 2023 it became a winning political party.

“A farmers’ party has stunned Dutch politics, and is set to be the biggest party in the upper house of parliament after provincial elections,” the BBC reported as the votes were being counted. “Results on [March 16th] showed the BBB party had won the most votes in eight of the country’s 12 provinces,” CNN reported a few days later. As BBB party leader Caroline van der Plas stated in the wake of the victory, “Nobody can ignore us any longer.”

Years of increasingly harsh agricultural regulations and widespread farmer protests in the Netherlands and elsewhere had led up to this point. Back in 2019 when US Senator Ed Markey and Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s original “Green New Deal” resolution called for the eventual elimination of “farting cows,” drastically cutting agricultural output for environmental interests struck many people as a novel concept. By 2023, conflicts between farmers and legislators had broken out across the globe.

Many examples come to mind. Sri Lanka’s government banned synthetic fertilizers for about six months in 2021, eventually rolling back the ban due to its exacerbation of mass food shortages and undernourishment across the country. In 2022 the Dutch government pushed unprecedented crackdowns on agriculture to reduce nitrogen emissions. “Farms next to nature reserves must cut nitrogen output by 70%,” the Economist reported. “About 30% of the country’s cows and pigs will have to go, along with a big share of cattle and dairy farms.” This would result in the loss of about 11,000 working farms, according to the Irish Times. Ireland’s government followed suit in 2023, pushing to cull 200,000 dairy cows over three years for the purpose of cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

Regulatory moves of this sort have resulted in mass farmer protests erupting not just in the Netherlands and Ireland, but also, Italy, Spain, Poland, and several other countries in 2022 and 2023. Already in the first month 2024, protests in Germany have broken out in opposition to newly announced legislation to cut subsidies and raise taxes on agricultural production. “Convoys of tractors and trucks gathered on roads in sub-zero temperatures in nearly all 16 federal states, while protesters clashed with police and leading politicians warned that the unrest could be co-opted by extremists,” Reuters reported on January 8.

The global debate over agriculture is more likely to heat up than to cool down in 2024, as it goes to the heart of a fundamental question of environmentalism: When humans want to transform their environment to enrich themselves and others, should they be allowed to?

Environmental change directed by productive human activity, with all the tradeoffs and unintended consequences bound to come along with it, is necessary for the enrichment of humanity and improvement of human living standards. Indeed, productive environmental change is the creation of physical wealth without which humans would rapidly go extinct.

This may take the form of cutting down lumber to rearrange into buildings that protect humans from the elements, drilling into the ground in search of fuels and materials with which to create and power technological inventions, tilling the earth and culturing livestock for the improvement of human nutrition, or countless other permutations. But whatever form it takes, you will not find improvements to human life in an environment that is being “conserved” in its current state. What many environmentalists call “conservation,” economists know as “stagnation.”

Many enemies of agriculture understand this, and often quite consciously choose environmental conservation over human enrichment, even while hundreds of millions of people suffer from undernourishment to this day (a problem that can be alleviated by increased agricultural supply driving down prices).

“We have to move away from the low-cost model of food production,” said the Dutch politician MP Tjeerd de Groot. DutchNews.nl reports that, “Dutch agriculture has to become a lot less efficient or the environment will suffer even more, say agro-environmental scientists.”

George Monbiot, award-winning environmental activist and columnist at The Guardian, takes this perspective to its logical conclusion in his Sunday Times (London) bestselling 2022 book Regenesis: Feeding the World Without Devouring the Planet, in which he advocates for government abolition of farming. “Campaigners, chef, and food writers rail against ‘intensive farming’ and the harm it does to us and our world,” he writes. “But the problem is not the adjective. It’s the noun.”

Monbiot defends the movement he calls the “Counter-Agricultural Revolution,” and argues that, “The new movement should begin by acknowledging an uncomfortable but well-established reality, a reality that has all too often been swept under the carpet: farming, whether intensive or extensive, is the world’s major cause of ecological destruction.”

“Just as improving the efficiency of irrigation leads to greater use of water, improving the efficiency of farming can cause a greater use of land,” he laments. “This is because efficient farming tends to be profitable, attracting capital.”

Some of the proposed environmentalism-motivated reforms to the agricultural industry are justified, such as the elimination of market-distorting farm subsidies. But the regulation-imposed reductions and ultimate abolition of agriculture would result in the mass culling (by starvation) of the human population, not just cattle. Probably far less than one percent of the current human population would be able to sustain itself in such conditions. The anti-agrarians tend to shrug off this profound implication of their policy preferences. Monbiot suggests that, “It is time to develop a new and revolutionary cuisine, based on farmfree food.” But of course, he’d rather not wait for those scientific and industrial breakthroughs to happen before the government eliminates “the most destructive human activity ever to have blighted the Earth,” namely farming.

The environmental conservationist movement, which in the case of agriculture has explicitly and openly shown its willingness to sacrifice human health and flourishing on their ideological alter, base their regulatory agenda on a fundamental conceptual error: They synonymize anthropogenic environmental change with degradation. Before they’re allowed to infringe on the freedoms of individuals to engage in agricultural production, the burden must be on them to at minimum prove their thesis that environmental transformation equals degradation.

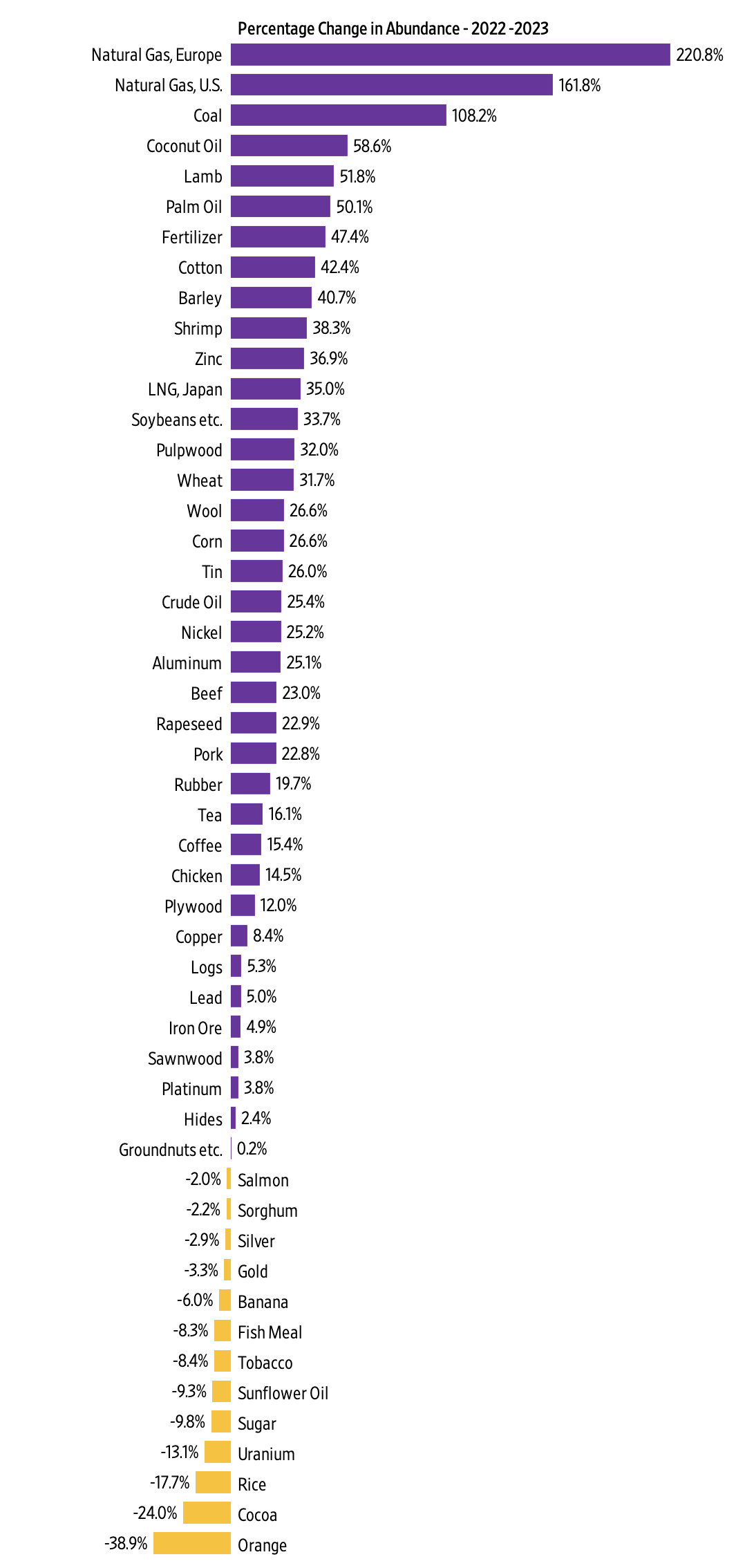

And this thesis is unjustified. All environmental transformation comes with upsides and downsides. Industrial production, agricultural or otherwise, has negative externalities such as pollution but also positive externalities such as economic growth which drives down the prices of necessities while facilitating more investment in the scientific and technological progress that provides positive-sum solutions to long-term environmental problems.

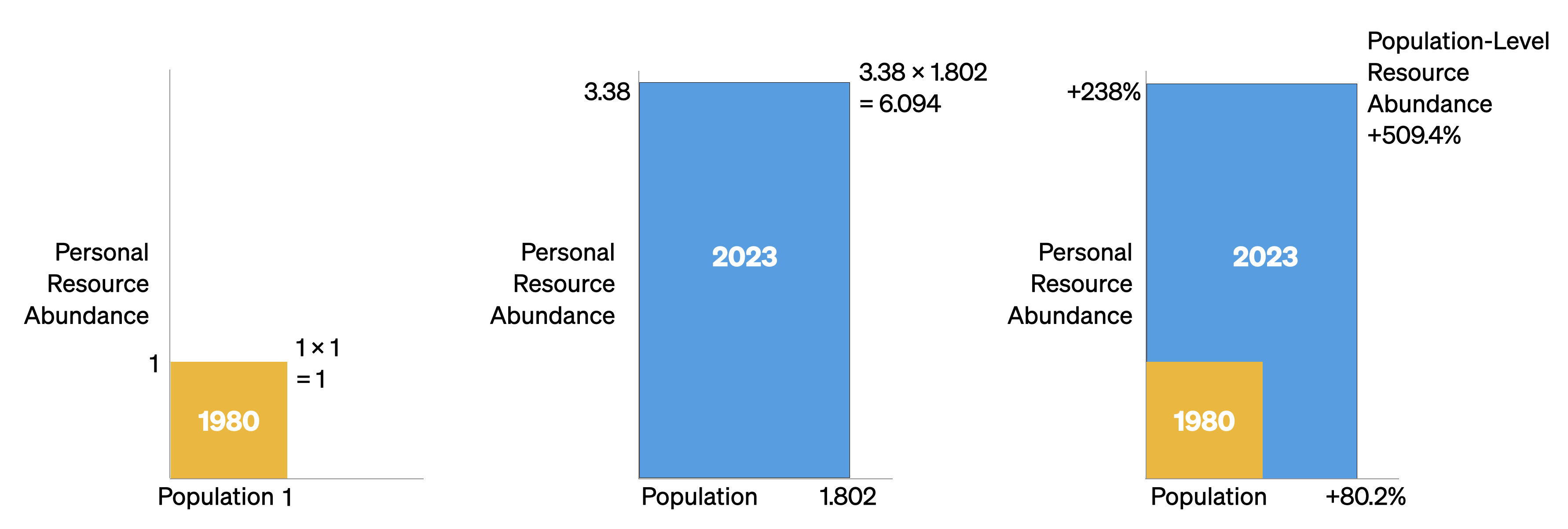

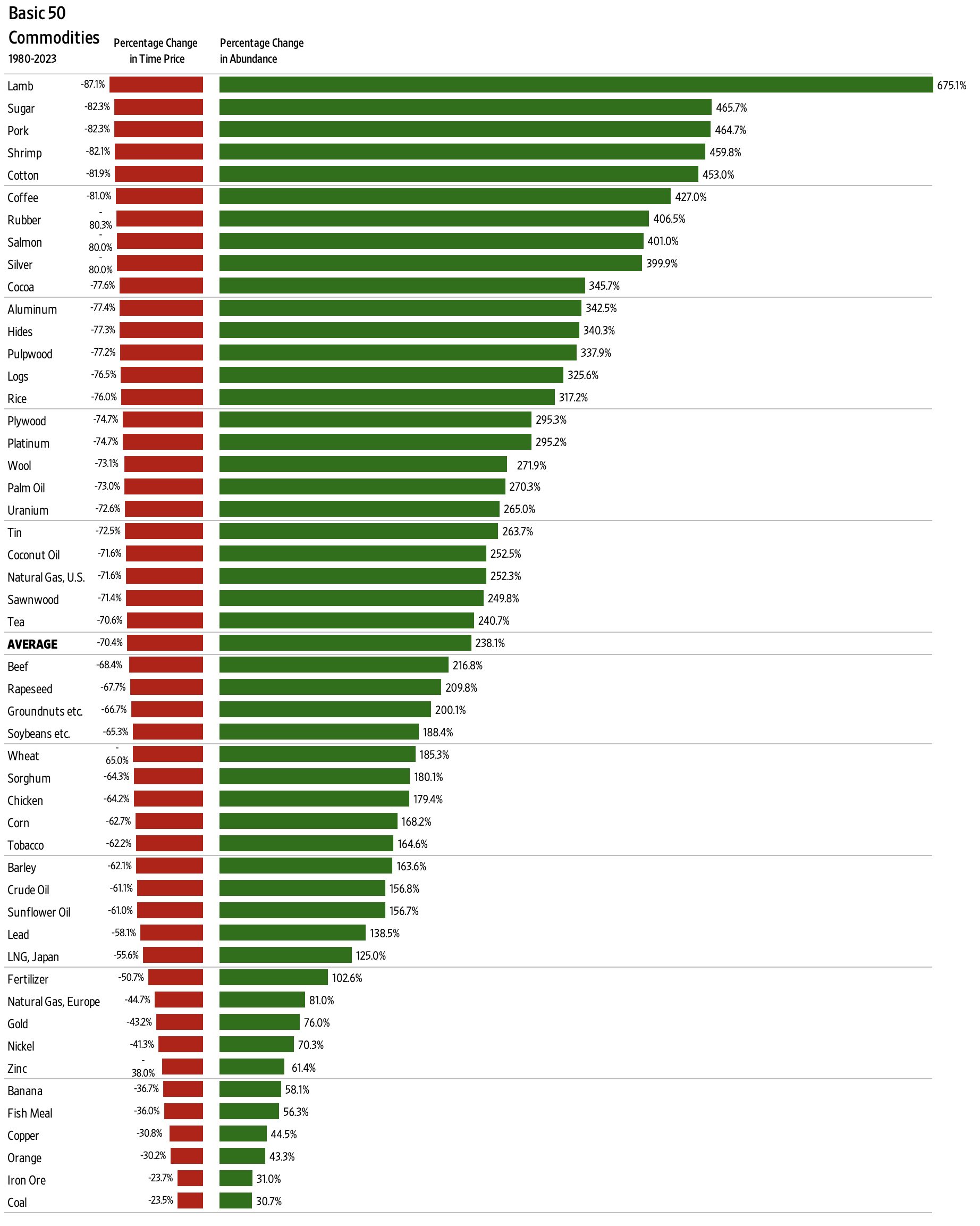

So far, the history of economic growth has shown the alteration of Earth’s surface through human volition and ingenuity to be far more helpful than hurtful to the prospects for human well-being. The supply of per-capita nutrition, which has been massively expanded since the industrial revolution through increased agricultural output, is a necessary input for the technological, scientific and economic progress that has improved human life expectancy and even drastically reduced climate-related danger to an all-time low.

As for the long-term future of anthropogenic climate change, the path of continued technological and scientific improvement to climate resilience and human adaptation is a far more believable story of sustainable prosperity than the only other one on offer: authoritarian-led mass undernourishment and impoverishment. That latter possibility is the one proposed by anti-agrarians because nothing less would be sufficient to make humans significantly reduce their agricultural production.

People changing their environment through profitable economic activity is a complex but overall positive phenomenon for the flourishing of civilization, and agriculture is among the clearest examples of that. But even if the freedom of people to improve their food supplies and other stocks of resources weren’t clearly net-positive for wider society, the hunches of environmentalists about future reversals of current trends in climate resilience would not come close to justifying the “Counter-Agricultural Revolution” that so many regulators would like to implement.

The coming year will see pivotal decisions made by governments and citizens the world over about how and to what degree people should be allowed to feed themselves and their associates in the market economy.