I argued in Part 1 of this essay that the modernization of American farming in the twentieth century helped alleviate multiple social ills. Powered tractors and harvesters reduced the physical burdens of most field work, but labor requirements were lessened by another innovation as well: the raising of farm animals like chickens, pigs, and dairy cows inside modern, biosecure automated barns.

My grandfather’s traditional Indiana farm in the 1930s raised five different kinds of animals (in addition to ten different crops). The feeding, watering, managing, and cleaning up after all these animals was a never-ending chore, one frequently assigned to the children. Modern livestock barns, which began arriving in the middle decades of the twentieth century, saved labor by automating most of the feeding, watering, and cleanout. In the late 1930s it required eight and a half hours of human labor to produce 100 pounds of broiler chickens, but by the early 1980s this had fallen to just six minutes.

Modern livestock operations have been dismissed by critics as “factory farms,” but bringing the animals into temperature controlled, biosecure environments protected them from nature’s extremes, provided safety from predators and reduced their exposure to disease. Tapeworm parasites were not eliminated from the meat supply in Europe and North America until small-scale pig rearing was replaced by confined production. Between the 1940s and 1980s the incidence of trichinosis in pig farming also fell, from four hundred clinical cases annually to sixty cases. The pathogen T. gondii was found in one out of five marketed hogs in the 1980s, but it has now been reduced by over 90 percent. Dr. Rodney Baker, a former president of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians, asserts, “By bringing the animals indoors and creating biosecurity, we’ve truly eliminated about 15 diseases and parasites we had back to the 1980s.”

Today’s livestock systems also emit fewer greenhouse gasses for every pound of production, thanks to better genetics and improved feeds. More efficient feed use brings more rapid weight gain, less manure, and less belched out methane for every pound of production. According to United Nations data, livestock production in the United States has more than doubled since 1961, yet direct greenhouse gas emissions from livestock have declined 11 percent. In 1950 the United States had twenty-five million dairy cows; now the number is only nine million, even though milk production is 60 percent higher. Frank Mitloehner, a professor of animal science and an air quality specialist at the University of California Davis, concludes that the climate burden of a single glass of milk in the United States today is two-thirds smaller than it was in 1950.

For pork production since the 1990s, average feed requirements for every added pound of weight gain have fallen by almost half. For chickens since 1950, average feed requirements per pound of live-weight broilers declined more than one third. In beef production since the seventies, every pound of meat now requires 12 percent less water, 19 percent less feed, 30 percent fewer animals, and 33 percent less land, while generating 18 percent less manure. Americans are eating too much meat—five times as much as they did in 1940—but until this excess is corrected the environment will gain better protection from modern compared to traditional systems.

One livestock system failing has been weak protection for the welfare of the animals. For pregnant sows in tight gestation crates and egg-laying hens in cramped cages, extreme confinement makes these animals easier to manage but it frustrates their instinctive behavior and compromises their physical and emotional wellbeing. These are failings that need to be corrected, but that can be done without a return to yesterday’s less productive and less secure barnyard and pasture systems. Recent experience in Europe shows farm animals can be given a good life indoors if barns are enriched and more spacious. Thanks to a 2008 European Union directive, European pigs are now required to have ample light, less noise, more space to lie down, and pregnant sows cannot be confined in crates. To help overcome boredom, the pigs must even be given objects they can manipulate—in other words, toys. In Europe, which actually raises twice as many pigs as the United States, these welfare enhancements have proved to be affordable.

It’s fine to be sentimental about our loss of farming traditions, but we should not view traditional methods as better for the environment. Farms in America today produce three times as much as they did in 1940. If we had tried to triple production using the low-yield, low-tech methods of the past the environmental damage would have been many times greater than it is today. In fact, we had already reached the environmental limits of traditional low-yield farming in the 1930s, when cropping was extended onto the drought-prone Southern Plains. When drought struck the soil blew away, creating a disastrous “Dust Bowl” and a stream of 400,000 environmental refugees. Only after 1950 did cropped area stop increasing, thanks to the uptake of nitrogen fertilizers and hybrid seeds. Corn production in the United States increased fivefold after 1940, yet the area planted to corn actually decreased by twenty percent, saving land for nature.

More recently, American farms have protected nature by adopting a wide range of new techniques, including no-till seeding, GPS-steered equipment, digital soil mapping, variable rate input application, drip irrigation, drones to scout the fields for pest pressures and crop disease, big data to calibrate an optimal response, and genetically engineered seeds that self-protect against insects with fewer chemical sprays. Thanks to such innovations, farming in America is far less energy and resource intensive today. Compared to 1980, corn production by 2015 required 41 percent less land for every bushel of output, 46 percent less irrigation water, 41 percent less energy use, and it emitted 31 percent less greenhouse gas. Total crop production in America increased 44 percent after 1981, yet total fertilizer use scarcely increased at all. Total pesticide use fell 18 percent in absolute terms, with insecticide use falling to less than 20 percent of the 1972 level. Modern agriculture is less resource intensive because, like much of the rest of our modern economy, it has become better engineered, GPS-located, more digital, sensor-informed, and computer-networked.

Modern farming in America has also become “multi-agricultural.” Most of our food is now being produced on large high-tech farms using eco-modern “precision agriculture” equipment, but this has left plenty of room on the land for other kinds of farms, mostly small farms that do not use high-tech production methods. Many of these are “life-style” farms. They make very little money growing food but are able to sustain themselves with off-farm income or retirement savings. In 1929, only 6 percent of American farms reported 200 days of work off the farm every year, but by 1997 this had increased to 35 percent. As of 2016, three out of five farms in America (defined as operations with at least $1000 in sales every year) were either pure retirement farms with little or no farming income, or hobby farms where agricultural production was not the primary occupation. These smaller farms produce very little food, but they keep people on the land and help sustain rural communities.

Many rural communities are struggling today, but it isn’t because today’s farms are struggling. Rural counties are coping with aging populations, job loss, family breakdown, and substance abuse, yet today’s job losses usually occur in the manufacturing and service sectors, not in agriculture. The rate of farm consolidation has slowed considerably over the past two decades, so few farms have been “lost” recently. In 2000 America had 2.16 million farms, and two decades later the number is only slightly smaller, at 2.02 million.

Many rural counties are relatively poor today, but few of the poor households live on farms. Only 2 percent of America’s farm households fall below the poverty line, compared to 14 percent of all U.S. households. The average income for farm households in America in 2016 was 42 percent above the average for nonfarm households, and the median net worth of households operating farms was an impressive $912,000. In Indiana where I grew up, some small farms may look poor from the road, but every acre of average-quality farmland in the state is worth about $7,000, so even small homesteads can be sitting on a considerable cushion of land wealth. Farmers in the state like to joke about living poor but dying rich.

Big farms produce most of our food today, but our more numerous small farms produce other things of considerable social value. In New England, where I now live, the total commercial sales made by all the farms (large and small) in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Rhode Island combined represent less than 1 percent of total national farm sales. Yet these New England farms are now drawing progressive young families into the countryside, anchoring local communities through regular CSA and farmers market sales, and attracting seasonal visitors from urban America by preserving a well-tended rural landscape.

In one fortunate respect, modern farming patterns in America have scarcely changed at all. The USDA defines a “family farm” as one where the majority of the business is owned either by the operator or by individuals related to the operator, even if some may not live in the operator’s household. By this definition, 96 percent of America’s farms and ranches today—including both large and small, modern and traditional—are still family farms. Family values thus continue to fuel the success of both large and small farms in America, no less than they did in our fondly remembered agrarian past.

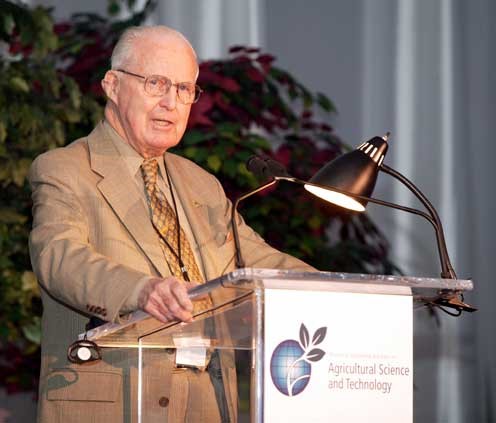

Robert L. Paarlberg is the Betty Freyhof Johnson ’44 Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the Wellesley College. This two-part essay is based on his new book, Resetting the Table: Straight Talk About the Food We Grow and Eat.