Urban and Suburban Americans are seldom well-informed about what goes on in rural America—a.k.a., “Flyover Country.” One prominent but mistaken urban legend is that rural America is in decline because small, diversified “family farms” have been replaced by large modern “industrial” farms. Time magazine said in 2019, “The disappearance of the small farm will hasten the decline of rural America.” This common view gets a number of big things wrong.

To begin with, the “decline” of rural America is in part a statistical illusion. Counties close to cities that were once classified as rural (“non-metro”) have regularly been reclassified as urban (“metro”) because of a steady spillover of new residents from cities. Between 1963 and 2013, 24 percent of all counties in America were for this reason reclassified as urban. Younger Americans may still be moving into cities, but more established American families are spilling outward at the same time, bringing their money with them, which enriches rural counties while eventually re-classifying them as urban. These more prosperous areas are then no longer counted as rural, so the improvement fails to show up in the data. The counties still classified as rural today hold only 14 percent of our population, and many are indeed struggling, but this is usually due to their distance from cities rather than a disappearance of small, traditional family farms.

Traditional small farms actually began disappearing in America a century ago, and the process is now nearly complete. Farm consolidations began when gasoline powered tractors dramatically reduced labor requirements on farms. This, combined with growing employment opportunities in urban factories, triggered an historic rural-to-urban labor migration. America’s farm population fell in the twentieth century from twenty-nine million down to just five million, even as the nation’s overall population was tripling. At the beginning of the twentieth century, farms were employing close to half of the entire U.S. workforce, but today it is just 2 percent. This labor shift proved to be an economic blessing because it made both urban and rural America more prosperous. Struggling small farms were replaced by more prosperous large farms, and the poor farm workers who left made a much better living in town.

The expensive new powered tractors and combine harvesters paid for themselves quickly on farms big enough to give them greater use, so it was larger farms prospered first from mechanization, then they bought out their smaller neighbors and got bigger still. Between 1910 and 2002, the total number of farms in America fell by nearly two-thirds while average farm size more than doubled. America’s larger farms today—the 146,568 farms with annual sales above $500,000—make up only 7 percent of all farms but account for 81 percent of all farm product sales.

This large farm bias in American agriculture is frequently criticized by those who associate small family farms with important cultural values such as personal dignity, community solidarity, basic equity, and local pride. It is also lamented because farm consolidation also put small rural towns at risk. A recent book by Ted Genoways, This Blessed Earth: A Year in the Life of an American Family Farm, describes what was left behind in the town of Benedict, Nebraska:

The school stands empty and abandoned; the only restaurant has been for sale for years. There’s a grain elevator, two well drillers, a feedlot outside of town, but otherwise there’s no work, nothing to do, no reason to be there instead of anywhere else.

De-populated towns like Benedict challenge my own optimism about modern farming. When I return to Indiana now to visit relatives, my back-country detours take me through empty rural hamlets with names like Barnard, Raccoon, Parkersburg, and Lapland. There is still a road sign pointing toward Raccoon, but the post office closed in 1934 during the Depression, and the town itself has long been abandoned. In the small towns still struggling to hang on, some people still show up for church on Sunday morning, and the main street café still serves some locals coffee and a sandwich, but it seems only a matter of time before these too will be gone.

This always makes me wistful and nostalgic, but I remind myself that nostalgia is just “memory with the pain removed.” The family farms and small towns of rural America brought painful memories along with the blessings.

For the farmers themselves, the most obvious drawback was unrelenting physical toil, which punished the body and often deadened to both mind and spirit. Albert Sanford’s 1916 book, The Story of Agriculture in the United States, records this truth through the eyes of a young boy. He saw his mother, “sober faced and weary, dragging herself, day by day, about the house with her entire life centered upon the drudgery of her kitchen, and all the rest of the world a closed book to her.” This boy also saw his father “broken down with long hours and hard work, finally relieved of the task of paying for the old place—just a few months before he died.”

Traditional small farms trapped large numbers of Americans in deep poverty. In 1910, despite favorable commodity prices and land values, the average household income on farms was still less than two-thirds that of non-farmers. In the 1930s, when prices and land values fell, farm income briefly dropped to just one-third of the non-farm level. On my grandfather’s small Indiana farm, despite the free labor provided by four healthy sons, his net return to labor and management in 1932 was a loss of $1,203.

Life on a small farm also meant social isolation during much of the week, and the work was physically unsafe, with roughly three thousand deaths every year from farm accidents at late as the 1950s. In addition, some of the cultural values embraced by small family farms were far from admirable. Children were valued more for their labor than for their learning, so education was sacrificed. As late as 1950, farm children still received, on average, three fewer years of schooling compared to urban children.

Farming communities and most small towns in rural America also lacked racial tolerance and cultural diversity. Descendents of white northern Europeans owned nearly all of the farms plus the shops in town, and they typically looked down on everybody else. In 1920 fifteen percent of all farm operators in America were nonwhites, but three-quarters of these were impoverished tenant farmers or sharecroppers in the South, abused and often terrorized by an all-white power structure.

Gender equity was missing as well. Women always did their share of the work on farms, but a century ago the role of farm operator was almost always reserved for the man. A popular newspaper described life on one early Illinois farm as “a perfect paradise for men and horses, but death on women and oxen.” Farm children could be put to work at an early age, so farm women were expected to produce children in large numbers. In 1900, they were raising twice as many children as their urban counterparts. Women were consistently more likely than men to leave farming, and less likely to come back.

It was the modernization of America’s farms in the twentieth century that finally alleviated most of these rural economic and social ills. Farm households in America today earn 42 percent more than non-farm households. The largest seven percent of these farms, those that produce more than 80 percent of our food, are the biggest earners, but the other 93 percent are usually far from poor, as we shall see. The income of this group is often derived from activities other than farming, which is often just a part-time hobby, but they too have found attractive ways to enjoy a country life.

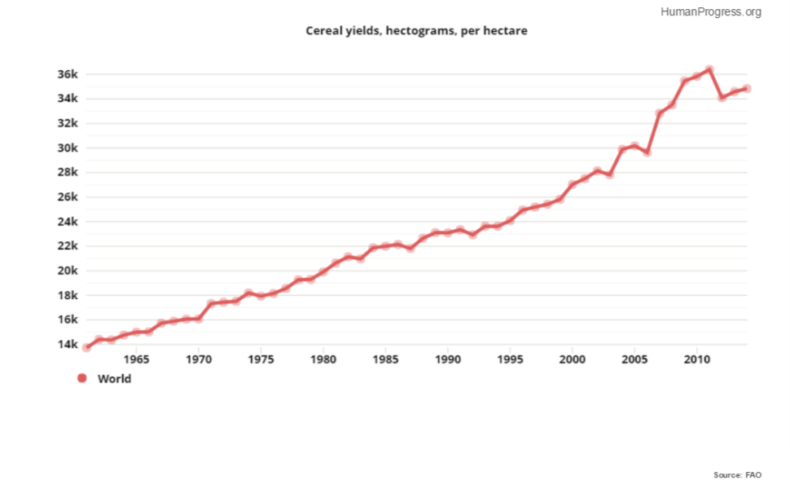

But what about damage to the natural environment? Here, as well, modern modern farming has proved to be more of a blessing than a curse. From today’s vantage point, pre-modern farming methods can appear more “sustainable” than today’s methods, because they were mostly chemical free, but the drawback was how little food they produced for every acre of plowed land. Agricultural output in the United States has tripled since 1940. If we had tried to triple production using the low-yield methods of the past, we would need to plow three times as much land, cut more forests, and destroy more wildlife habitat. Fortunately, thanks to an introduction of hybrid seeds and greater use of manufactured chemical fertilizers, America’s farms found a way to increase crop yields dramatically on lands already plowed, enough by 1950 to halt agricultural land expansion entirely.

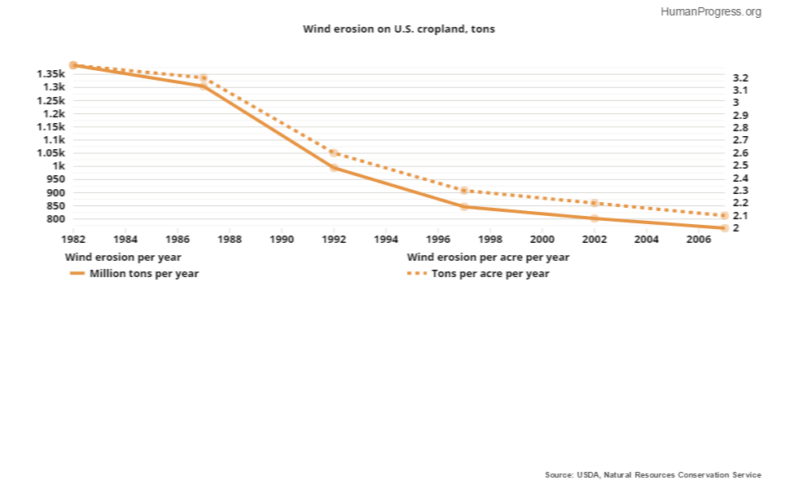

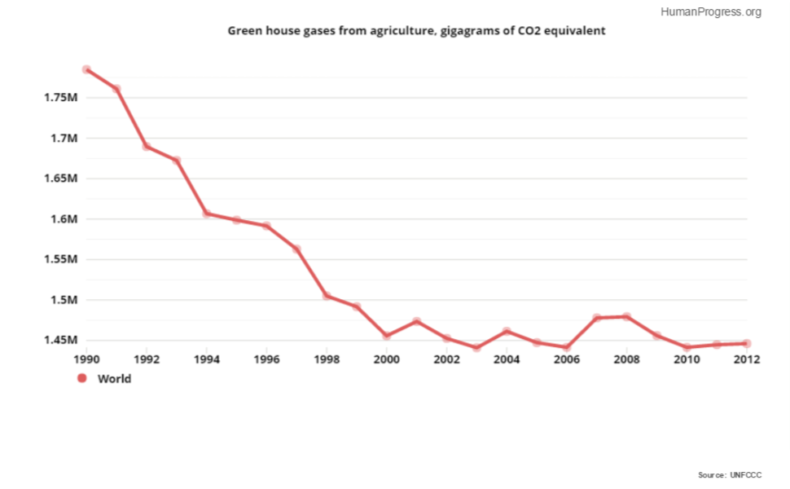

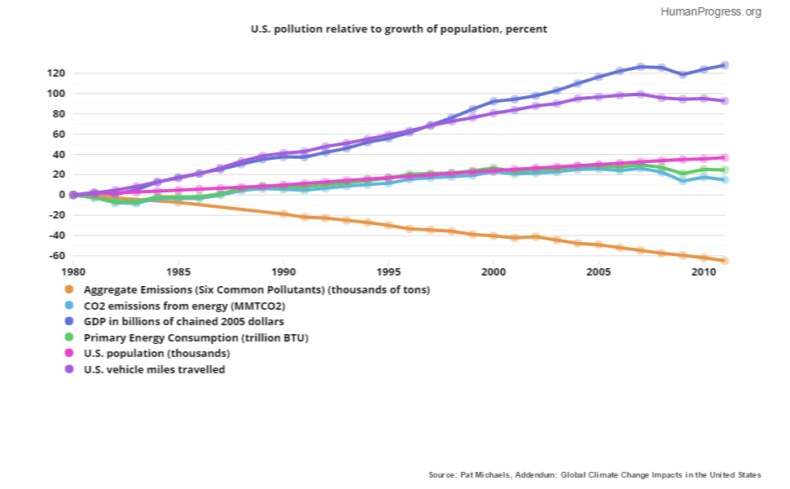

This saving of land as production increased was achieved initially through increased applications of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, bringing a new kind of environmental risk. Yet beginning in the 1970s these excesses began coming under far better control, thanks to new breakthroughs in agricultural science such as GPS-steered equipment, digital soil mapping, variable rate chemical applications, and genetically engineered seeds that contained insect damage with fewer chemical sprays. Water use was conserved through laser-leveled fields and drip irrigation, and less diesel fuel was burned thanks to innovative no-till seeding methods. America’s large modern farms today have learned how to grow more while using fewer inputs, thanks to innovations in what is called “precision agriculture.”

This beneficial shift toward eco-modern farming will be described in greater detail in Part II of this essay, scheduled to appear next week. The supposed environmental costs of farm modernization, it will show, are just one more urban legend, along with the supposed rural “decline” brought on by modern farms.

Robert L. Paarlberg is the Betty Freyhof Johnson ’44 Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the Wellesley College. This two-part essay is based on his new book, Resetting the Table: Straight Talk About the Food We Grow and Eat.