Summary: Amid record drought, communities in the American West are finding ways to use far less water. This article examines how innovations such as wastewater recycling, desalination, and water markets conserve water while allowing the West to prosper and grow.

The American West is in the grips of its worst drought in more than a millennium. Reservoir levels in some areas have dipped to all-time lows. The shortages are especially dire in the Colorado River Basin, which supplies water to 40 million people and irrigates four million acres of farmland.

There are plenty of gloomy headlines on the West’s water crisis. But beyond the front page is a lesser-known story of remarkable adaptation: over the past few decades, western communities have found ways to use far less water, even as populations grow and economic output increases. It’s a testament to the ability of humans to respond to water scarcity, and it illustrates what more is needed to enable continued adaptation in the future.

Consider Las Vegas. Since the drought began two decades ago, the city has cut per capita water use by half. Total water use has fallen by 26 billion gallons since 2002, even as its population has grown by 800,000 residents. Or take Phoenix, another fast-growing metropolitan area. Since 1980, the city’s population has more than doubled, yet its total water use has declined by one-third.

The same is true in much of the American West. Since 2000, Albuquerque’s per capita water use has fallen 48 percent; Denver’s by 38 percent; and Los Angeles’ by 29 percent. San Diego’s water use has plummeted from nearly 220 gallons a day per person in 2007 to less than 140 gallons per person. Total water use in the city is down 40 percent. A recent study of 20 western cities found that population growth from 2000 to 2015 increased by an average of 21 percent, while total water use declined by an average of 19 percent.

How has this happened? In his book Water Is for Fighting Over: And Other Myths about Water in the West, the writer John Fleck explores the impressive ability of people to adapt to water scarcity without sacrificing economic growth. When people have less water, Fleck writes, they find ways to use water more efficiently. Often, that’s through stormwater capture, wastewater recycling, aquifer storage, lawn buyback programs, and other innovations.

In San Diego, city officials have invested in desalination plants, sewage recycling, raising dams, and other water-saving measures. A new wastewater recycling project is expected to meet roughly half of the city’s drinking water needs by 2035. In Nevada, water managers have implemented “cash for grass” programs, which offer rebates to businesses and residents who tear out lawns and replace them with water-efficient alternatives. The program has resulted in significant per capita water-use reductions, according to the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

Modern cities, it turns out, are quite water efficient, especially when compared to irrigated thirsty desert croplands. In Arizona, building houses to accommodate a growing population has resulted, somewhat counterintuitively, in significant water savings in the region. By one estimate, converting 100 acres of Arizona cotton fields into subdivisions with quarter-acre lots can cut water use by roughly a third.

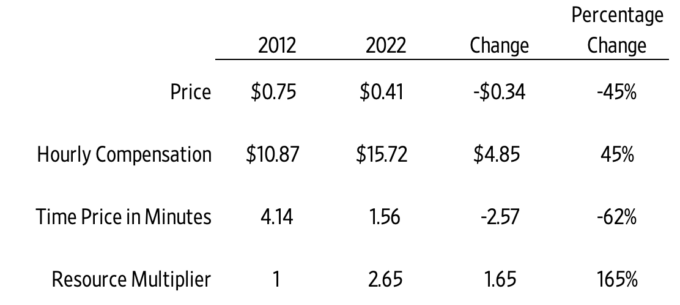

Prices also play a role. Water prices in San Diego reached as high as $1,736 an acre-foot (enough water to cover an acre of land, about 326,000 gallons) last year, up from $620 in 2007, encouraging conservation and spurring water-saving innovations. In other parts of the West, however, water prices remain low despite recent drought conditions. Salt Lake City, for instance, has among the lowest water prices of major U.S. cities; it also consumes more water than other desert cities.

The agricultural sector, which uses roughly 80 percent of all water in the West, is also conserving water. In California, for example, farm water use in 2015 was 14 percent less than in 1980, while economic output from farming was up 38 percent. This is due in large part to rising crop yields. Farmers can now grow more crops on less land while using less water, enabling them to transfer some of that saved water to cities or, in some cases, to increase environmental flows for fish and wildlife habitat.

This adaptation story is one to celebrate and sustain. Contrary to apocalyptic media reports, western communities have decoupled water consumption from economic growth. But despite these recent successes, more water conservation is needed in response to today’s prolonged drought conditions.

Tapping water markets is one way to do so. Markets allow users to move water from lower-value to higher-value uses, thereby encouraging conservation and promoting more efficient use. In practice, however, a variety of legal and policy barriers can prevent win-win water trades from occurring. Reducing barriers to water markets is crucial to enabling further adaptations to drought in western states.

The American West has a remarkable ability to adapt to water scarcity. Current drought conditions are bad, but they are likely to spur even more water-saving innovations and policy reforms in the future. Ultimately, that ingenuity will enable people to conserve water while allowing the West to continue to prosper.