Summary: Chocolate and roses began as rare, prestigious goods, but industrialization and global trade have made them far more affordable, freeing up more time for what matters most.

Long before heart-shaped boxes lined supermarket aisles, cacao was consumed as a bitter ceremonial drink in Mesoamerica and valued enough to function as a medium of exchange. Among the Aztecs, cacao beans could be traded for everyday goods, and the beverage prepared from them was associated with wealth and status. Chocolate entered Europe in the 16th century as a rare and expensive commodity, with high prices of sugar and spices helping to keep the elaborately prepared drink from the hands of ordinary people. Only with the rise of industrial processing, global trade, and mass production in the 19th and early 20th centuries did chocolate steadily migrate from royal courts to average shop counters, becoming a common indulgence for many children and sweet-toothed adults.

Despite that, there is a prevailing sentiment that everyday luxuries like chocolate are becoming unaffordable, and two-thirds of Americans remain “very concerned” about the rising cost of food and consumer goods, according to the Pew Research Center. This is especially the case for holiday spending, with 2 in 5 Americans reporting Valentine’s Day activities being unaffordable in 2026.

But sticker prices are often misleading. A better way to judge affordability—the method economists increasingly favor—is to ask how long someone has to work to buy something. When prices rise, but wages rise faster, the functional price of a commodity goes down, because more can be bought with the same amount of work, or the same can be bought with less work.

Seen through the lens of time prices, Valentine’s chocolate tells a surprisingly hopeful story.

In 1929, around the time See’s Candies was establishing its reputation, a pound of quality chocolate cost about 80 cents. That same year, the average wage in the U.S. was 56 cents per hour, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A box of chocolate for that special someone would have cost nearly an hour and a half of work.

Today, a one-pound box of See’s assorted chocolates sells for $33.00, just a fraction more than today’s median blue-collar hourly wages of $31.95 per hour. In other words, the time price for that box of indulgence has fallen by 24 minutes over the last century, making the same romantic gesture 28 percent more affordable.

The same applies to the classic bouquet of roses. Today, Trader Joe’s sells a dozen roses for $10.99, or a time price of a mere 20 minutes for the average U.S. worker. That price would have been considered a bargain even 40 years ago, when the same median hourly wage was $9.00 per hour. The time price of roses has fallen by 71 percent in just four decades.

Moreover, before modern greenhouses and supply chains, roses were not even reliably available in February across much of the world. Like the endless supermarket shelves stocked year-round with once-seasonal tropical fruit, technological progress and globalization have made romantic gestures possible in the depths of winter.

Romance has not become a luxury good. If anything, the opposite is true. The time required to buy chocolate and flowers has fallen dramatically, and we now have constant access to goods that were once rare commodities.

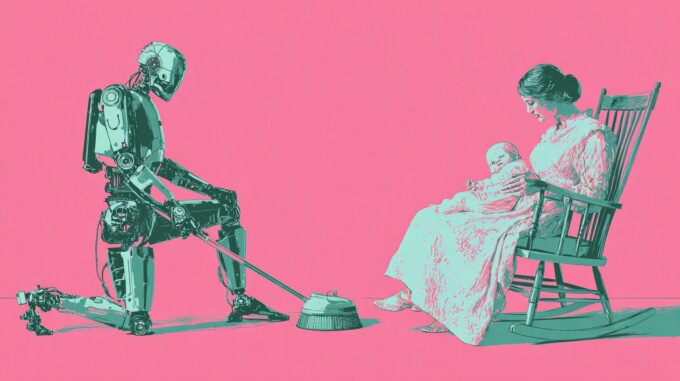

For those concerned about consumerism spoiling romance, advancements in time prices are still a welcome boon. When people don’t have to work as long to meet their basic needs, hours free up for physical closeness, quality time, and immaterial romantic gestures. Love, it turns out, is more accessible than ever.