Summary: Access to agrochemicals and mechanization has lifted millions of people from poverty. A backlash against industrial farming leads to inefficient alternatives, such as organic farming, which can be worse for the environment. The aftermath of Sri Lanka’s agrochemicals ban demonstrates the damage that occurs when people put ideology before evidence.

Agriculture is essential for satisfying the basic human need for food and helping to reduce poverty. Half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture, which employs roughly a quarter of the world’s labor force.

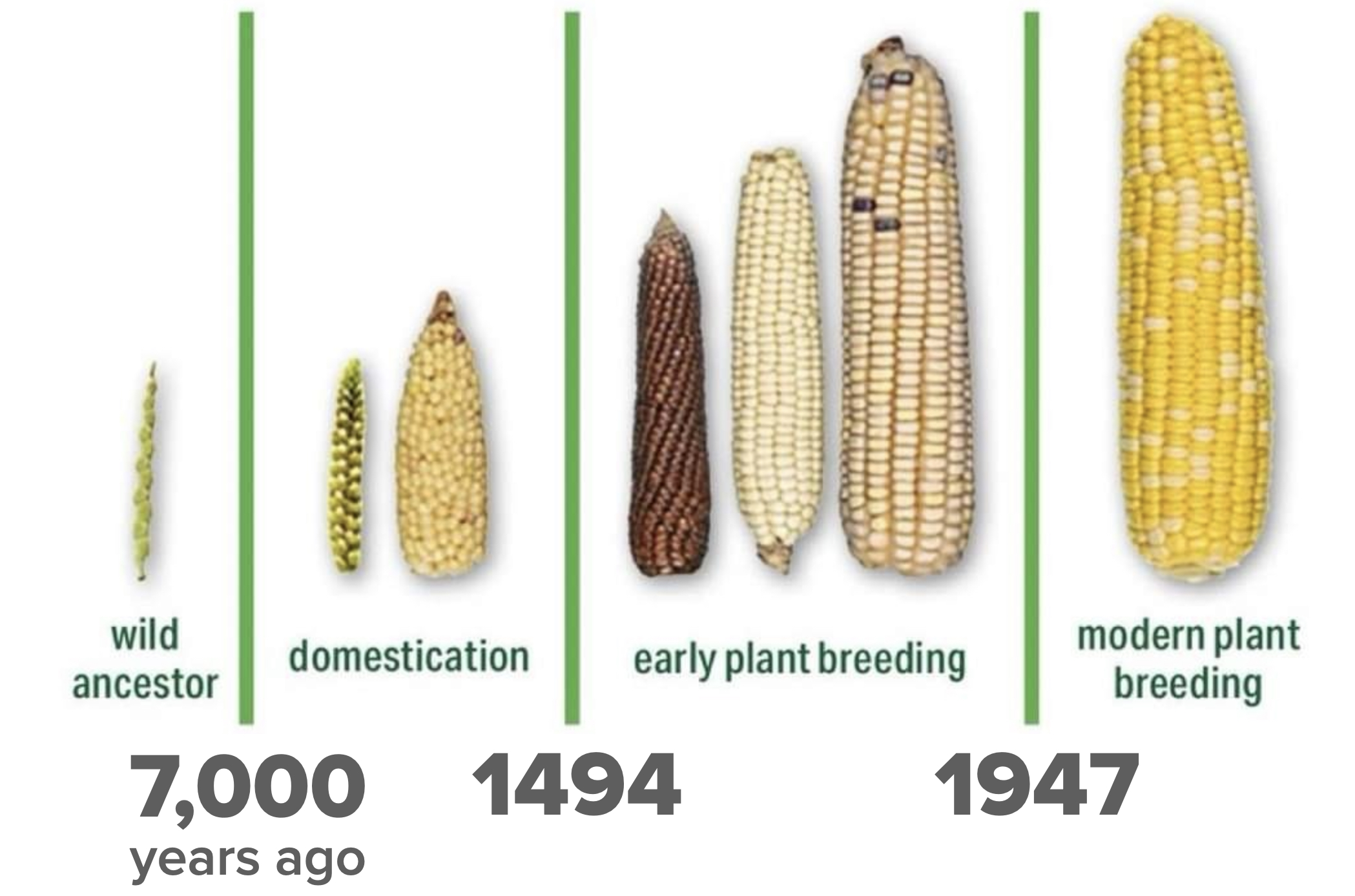

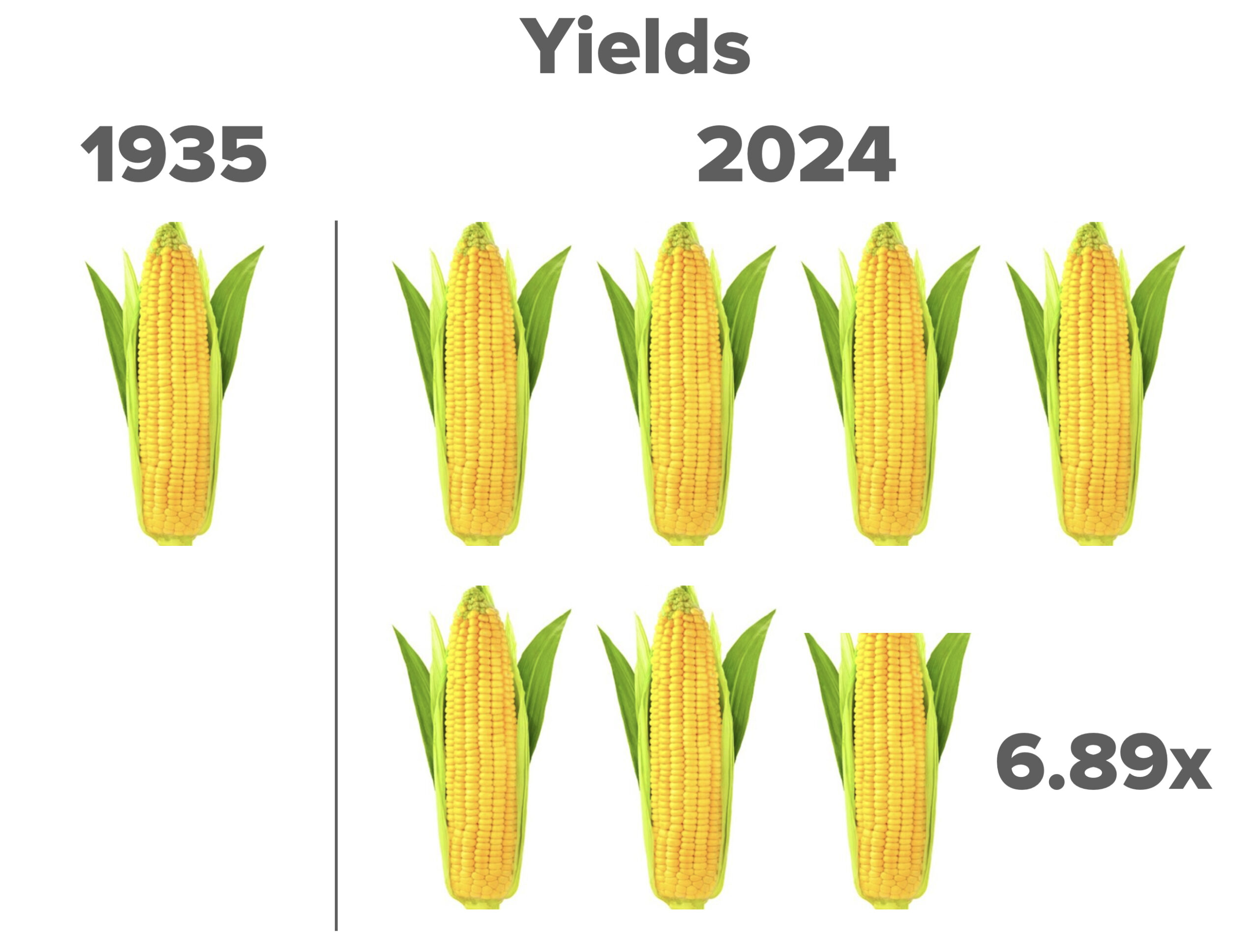

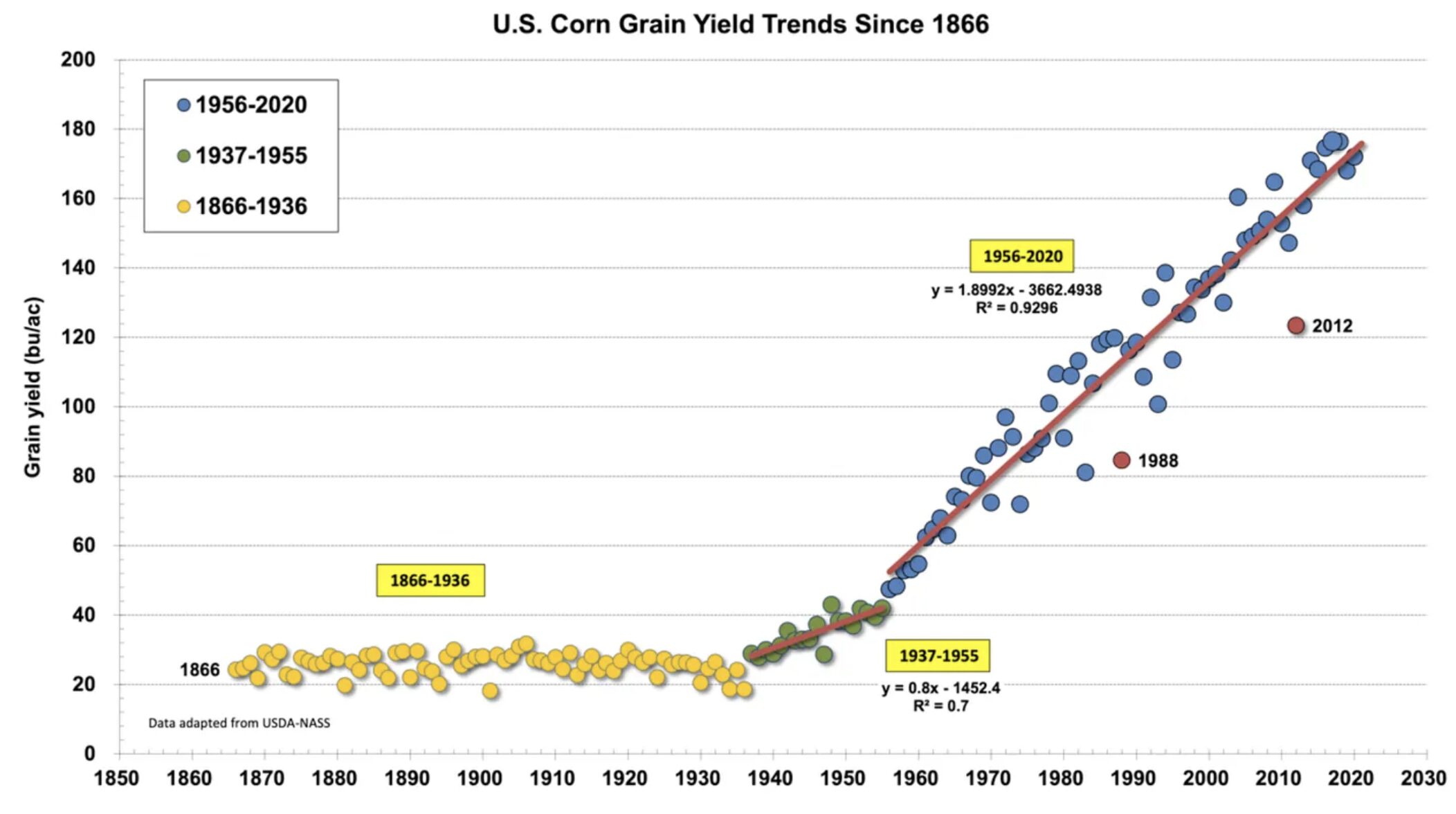

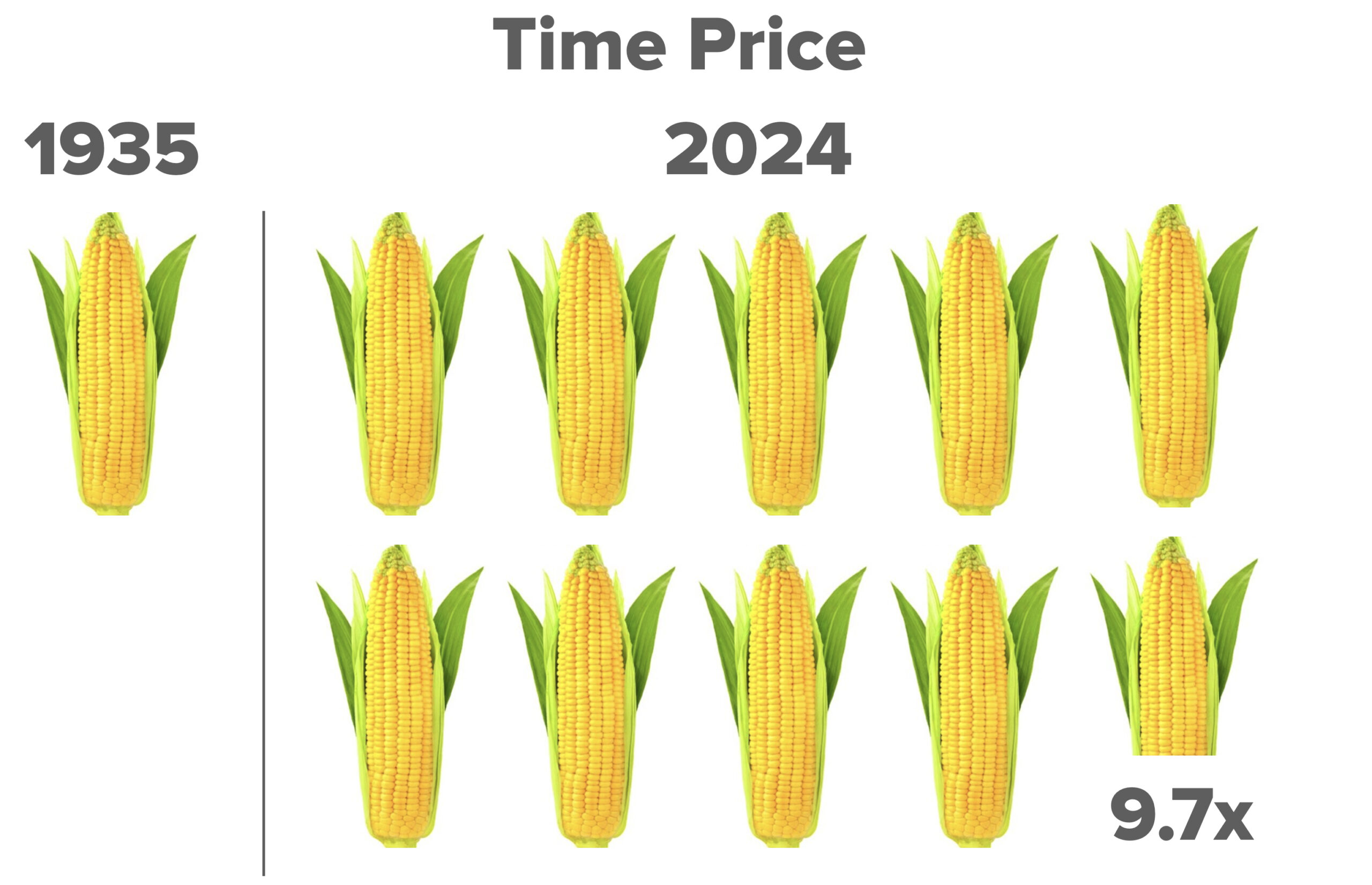

Thanks to the Green Revolution—a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw significantly increased crop yields and agricultural production—it became easier to feed more people with less land. The Green Revolution involved adopting newer methods of cultivation, including mechanization, modern crop varieties, and agrochemicals, including fertilizers, irrigation, pesticides, and herbicides.

Before the Green Revolution, hunger was common. If India, for example, had stuck to its traditional farming methods, millions of people would have starved, particularly children. Once the subcontinent employed modern agricultural techniques between 1965 and 1970, wheat yields nearly doubled in India and Pakistan. That has required only 30 percent more land.

Today, there is a backlash against modern farming methods, mostly from extreme environmentalists who oppose agrochemicals and gene-editing technologies. Fear-mongering activist messaging can be powerful and dangerous, as demonstrated by what has happened in Sri Lanka.

When Sri Lanka started using artificial fertilizers in the 1960s, rice yields tripled, and the country became self-sufficient in rice production. It could even export rice.

In 2021, Sri Lanka’s President Gotabaya Rajapaksa told a United Nations summit that he was concerned about the country’s “increasing use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and weedicides that led to adverse health and environmental impacts.”

Ignoring proven scientific practices, Rajapaksa banned all imports of chemical fertilizers, forcing Sri Lanka’s millions of farmers to go organic virtually overnight. Without access to agrochemicals, average rice yields in Sri Lanka were reduced by 30 percent. Sri Lanka was forced to spend $450 million on rice imports. Tea production, the country’s prime export, also fell by 18 percent.

The result was economic collapse, with poverty rates nearly doubling between 2021 and 2022. Sri Lanka has become the first country in the Asia Pacific region in 20 years to default on foreign debt. That should be a cautionary tale against changing established farming practices to organic ones for supposedly environmental reasons.

Agriculture is all about trade-offs. Although they have some negative environmental impacts, agrochemicals help farmers grow more food on less land, which is critical for developing countries that rely on agriculture to combat starvation and for export income.

High-yield output also correlates with positive environmental outcomes by reducing land used for agriculture. A meta-analysis comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture found that organic farming yields are between 5 percent and 34 percent lower than those from conventional agriculture. Another study found that if England and Wales aimed for 100 percent organic agriculture, net greenhouse gas emissions would rise due to the need to clear additional grasslands or forests to compensate for the productivity loss. Organic farming usually increases greenhouse gas emissions and habitat loss because more land is cleared to rear animals or plant more crops. Habitat loss is the largest threat to biodiversity.

We can feed more people and preserve biodiversity by improving land-use productivity through increasing crop yields. Achieving that will require more machinery, gene-editing technologies, and agrochemicals. It is possible to feed the world’s population a healthy and nutritious diet, but to do so we need to ensure that all farmers have access to modern farming methods, which we know save lives.