Summary: Recent praise for feudalism overlooks the grim reality of life under it. Far from being a system of mutual care, it was defined by hardship, hunger, and oppression for the many and insecurity even for the few in power. History shows that markets—not monarchs—turn self-interest into shared prosperity.

“Feudalism is so much better than what we have now. Because at least in feudalism, the leader is vested in the prosperity of the people he rules,” declared Tucker Carlson recently on The Tucker Carlson Show. His guest, writer Auron MacIntyre, agreed enthusiastically. Carlson added, “If all your serfs die, you starve.” McIntyre replied, “Yeah. There’s a true incentive to care for those people.”

The conversation sparked ridicule online, but it also reflected a broader, bipartisan trend. As Amanda Mull observed in The Atlantic, social media has grown “strangely nostalgic for life in the Middle Ages.” Samuel Matlack of The New Atlantis noted the puzzling frequency of the argument that the preindustrial past may have been superior to modernity.

Carlson’s reasoning implies that feudal lords, out of self-interest, nurtured the well being of their serfs. Yet the system he imagines has more in common with modern markets than with medieval Europe. Adam Smith explained the principle long ago: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” If customers are displeased, businesses collapse. Markets channel self-interest into mutual gain in ways that feudalism never could.

History makes that clear. Start with life expectancy. Even kings in the feudal era rarely lived into old age. Between the 11th and early 15th centuries, most European monarchs died young. Alfonso VI of Castile and León, who reached 79, was the outlier. Only a few others across England, Aragon, Germany, and France managed to live into their 60s. For most rulers, living to 70 was unattainable, and commoners fared far worse.

The average European life expectancy in the 11th century hovered around 25 years, driven down by staggering child mortality. Historian Richard Hoffmann notes that of 1,000 children who survived infancy, as many as 250 died by age seven. Only between 40 and 70 percent ever reached adolescence. In contrast, life expectancy in Europe today exceeds 80 years.

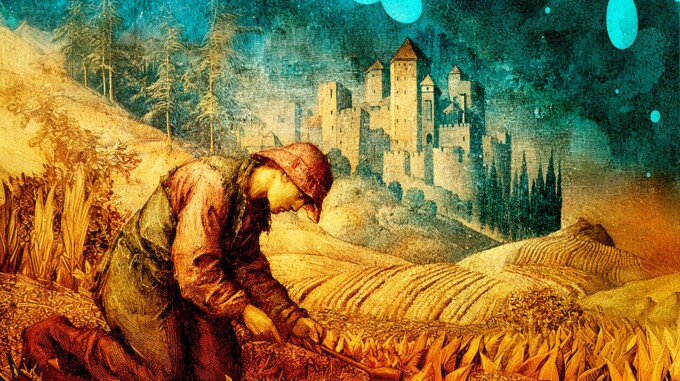

Nor were feudal peasant lives leisurely. A persistent myth claims medieval peasants worked less than modern people. This misconception stems from an early estimate by historian Gregory Clark, who suggested peasants worked only 150 days annually, an estimate he later revised upward to about 300. That number is higher than today’s 260 working days, even before accounting for paid holidays and vacation. Serfs’ labor was grueling and often damaging to their health. They were legally bound to the land, compelled to work their lord’s fields in addition to their own, and held few rights against mistreatment.

Another common misconception is that feudal societies provided security in exchange for labor. In reality, medieval Europe was marked by frequent famine, war, and violence. Crop failures were devastating, and local lords often demanded their share of harvests regardless of whether peasants had enough left to survive. Raids and small-scale wars were constant features of life, and the people at the bottom had little protection when armies swept through their fields. Unlike citizens in modern states who benefit from the rule of law and relatively impartial modern justice system, peasants depended on their lords for protection but had no meaningful recourse when those same lords were the source of oppression. For most peasants, daily life combined backbreaking labor with exposure to hunger, violence, and disease, far from the idyllic stability sometimes imagined today. (I explore these harsh realities in my forthcoming book, The Grim Old Days: An Introduction to the Preindustrial Past).

In Russia, where serfdom endured until 1861, abuse could be extreme. Serfs were frequently beaten or killed without legal consequence. The notorious case of Darya Saltykova, who tortured more than 100 of her serfs to death, was unusual only in that she faced punishment.

Material conditions were equally bleak. In 1300, the United Kingdom’s average income was about $1,657 in today’s dollars. That represented one of the wealthiest regions in Europe at the time. Even kings lived in poverty by modern standards, while ordinary peasants experienced deprivation that is difficult to imagine today.

When Friedrich Hayek titled his classic The Road to Serfdom, he did not mean it as praise. He used “serfdom” to warn against a return to systems that crushed freedom and prosperity. Carlson’s romantic vision of feudal life bears little resemblance to the historical reality.

Modern economic systems, for all their flaws, have delivered longer lives, safer working conditions, and unprecedented prosperity. The record of feudalism offers no reason to wish for its return.

This article was originally published at LA Progressive on 9/22/2025.