Introduction

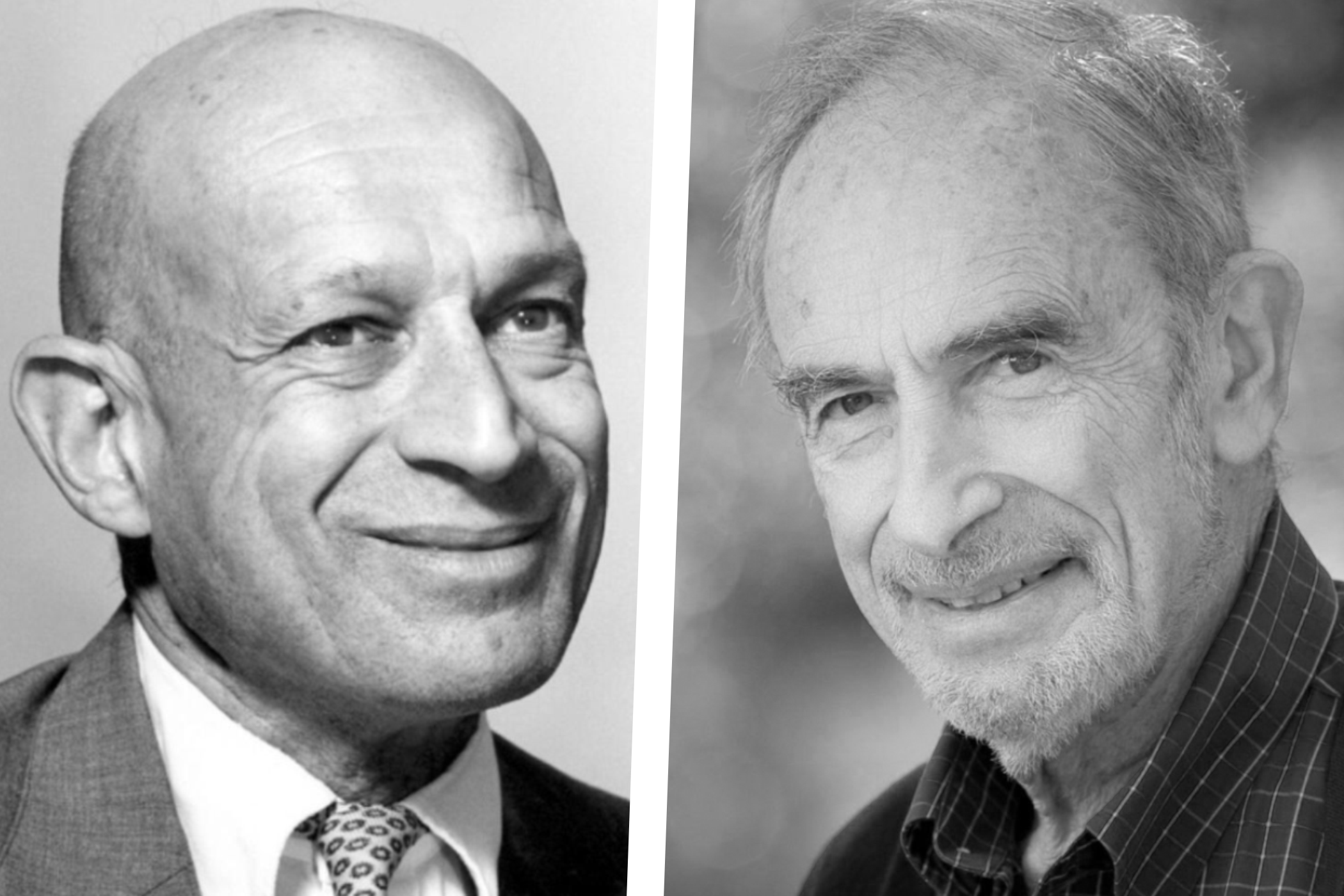

During the 1970s, University of Maryland economist Julian Simon and Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich provided the public with two very different visions of the future on the pages of Science and a variety of other publications. The dystopian Population Bomb (Ehrlich, 1968) and the cornucopian Ultimate Resource (Simon, 1981) give the flavour of this debate. Both Simon and Ehrlich agreed that there was a relationship between abundance of resources and population growth, but disagreed on the nature of the relationship. A neo-Malthusian, Ehrlich argued that, as population increased, resources would become scarcer and prices would increase dramatically. Simon argued the opposite. He claimed that as population increased, resource prices would actually decline. Simon admitted that temporary price spikes would occur, but predicted greater abundance of resources in the long run. He argued that people would respond to price spikes in four ways: they would consume less, search for new supplies, invent and discover substitutes, and recycle. These four actions would result in long-run prices that were even lower than before the spike.

The Bet

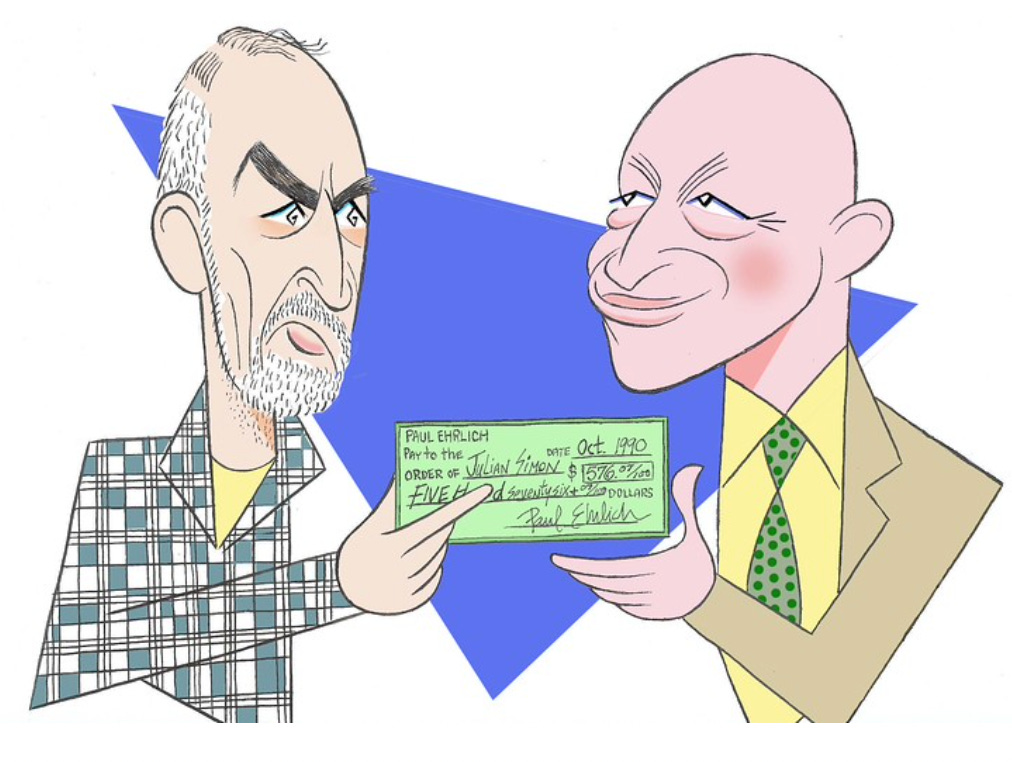

Frustrated with the limited progress that he was making in the argument, Simon upped the ante and challenged Ehrlich to a wager. Ehrlich would choose a $1,000 basket of raw materials that he expected to become less abundant in the coming years and choose a time period of more than a year, during which those raw materials would become more expensive. At the end of that period, the inflation-adjusted price of those materials would be calculated. If the real price of the basket was higher at the end of the period than at the beginning, that would indicate the materials had become more precious and Ehrlich would win the wager; if the price was lower, Simon would win. The stakes would be the ultimate price difference of the basket at the beginning and the end of the time period.

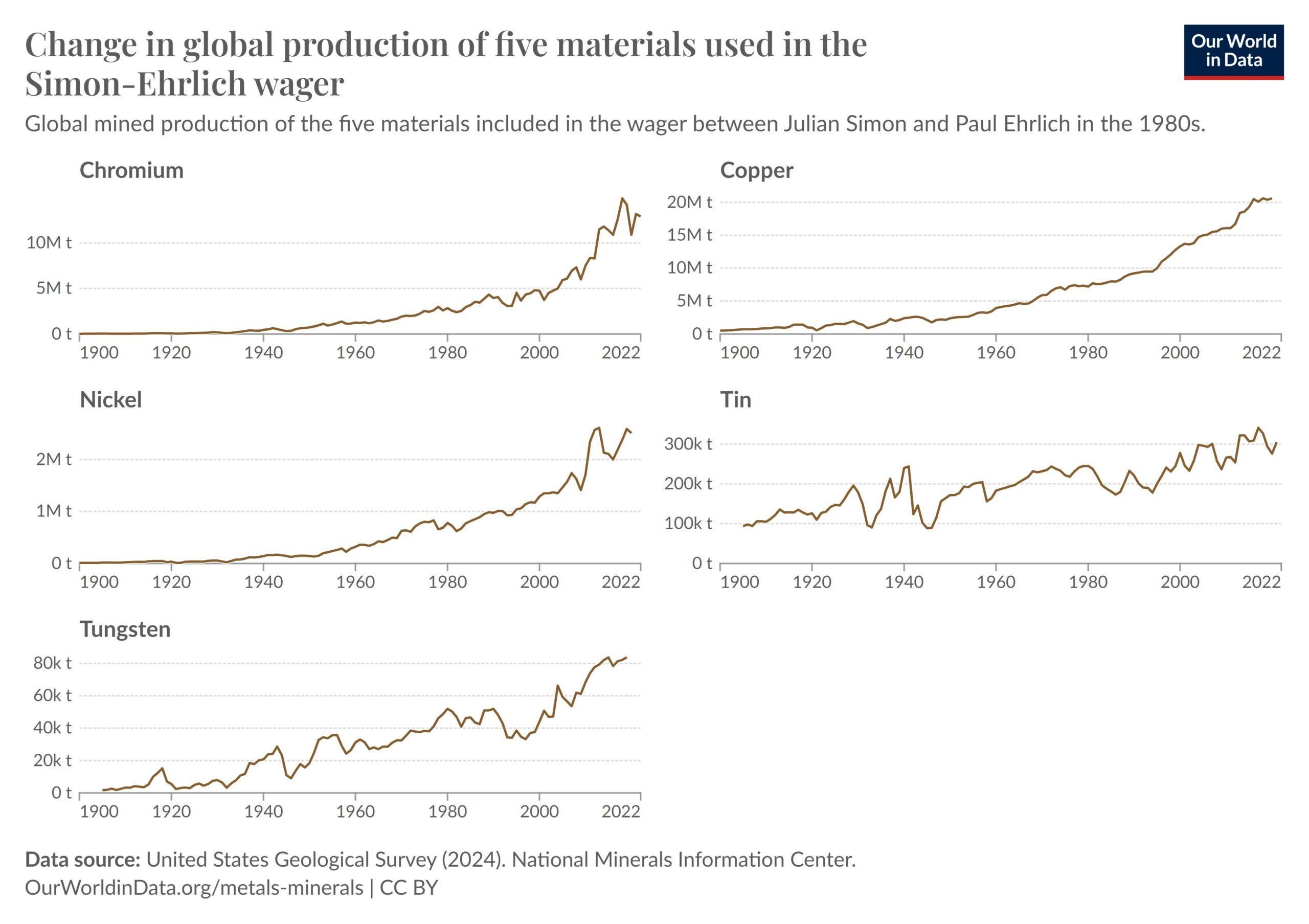

Ehrlich chose copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten, and the $1,000 wager was sealed in a contract on 6 October 1980. Ten years later Simon received a cheque from Ehrlich in the amount of $576.07, dated 11 October 1990. Adjusted for inflation, the real price of the basket of metals had fallen by 36 per cent.

It should be noted that Simon originally proposed a $10,000 bet. After Ehrlich and his two partners (Harvard University scientist John Holdren and University of California at Berkeley ecologist John Harte) agreed to the idea, Simon reduced the amount to $1,000. He argued that the purpose of the wager was the principle, not the amount. Ehrlich and his partners complained about the reduced size of the wager. However, without this reduction, the Ehrlich trio would have lost $5,760.70 instead of $576.07. Simon reduced their losses by 90 per cent, saving them $5,184.63.

Was Simon Just Lucky?

A number of researchers have argued that Simon was lucky. Several have analysed prices of the same basket of metals over ten-year intervals, including Kiel, Matheson, and Golembiewski (2009), McClintick and Emmett (2005), and Perry (2008).

Kiel et al. conducted the most comprehensive study, looking at price changes of the five metals in ten-year intervals between 1900 and 2007. They used nominal price data collected and reported by the U.S. Geological Survey, and then adjusted those prices for inflation using the US Consumer Price Index (CPI). As the CPI only goes back to 1913, Kiel et al. converted the first 13 years to real prices using estimates provided by McCusker (2001).

Using 98 ten-year intervals based on successive years between 1910 and 2007, they found that Ehrlich would have won the bet 61.2 per cent of the time with an average return of 10.5 per cent. They also used 25-year intervals and found that Ehrlich would have won 59 per cent of the time with a return of 13.8 per cent. The rate of return was calculated as the percentage difference between the inflation-adjusted prices for the intervals.

Our analysis covers the period from 1900 to 2019, or 110 ten-year intervals. We relied on the U.S. Geological Survey for our data as well. We made two modifications to the Kiel et al. methodology, namely using time prices and the war clause.

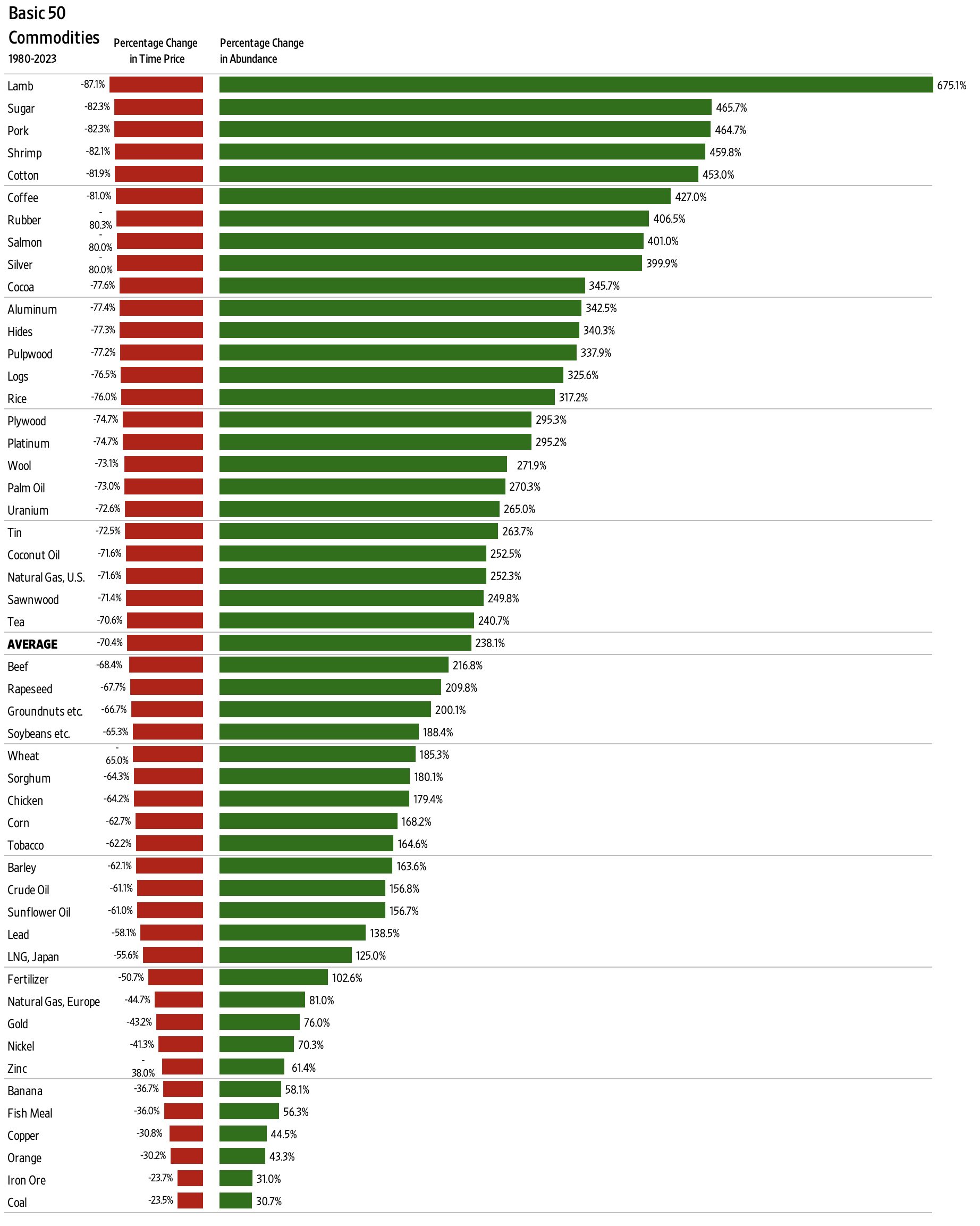

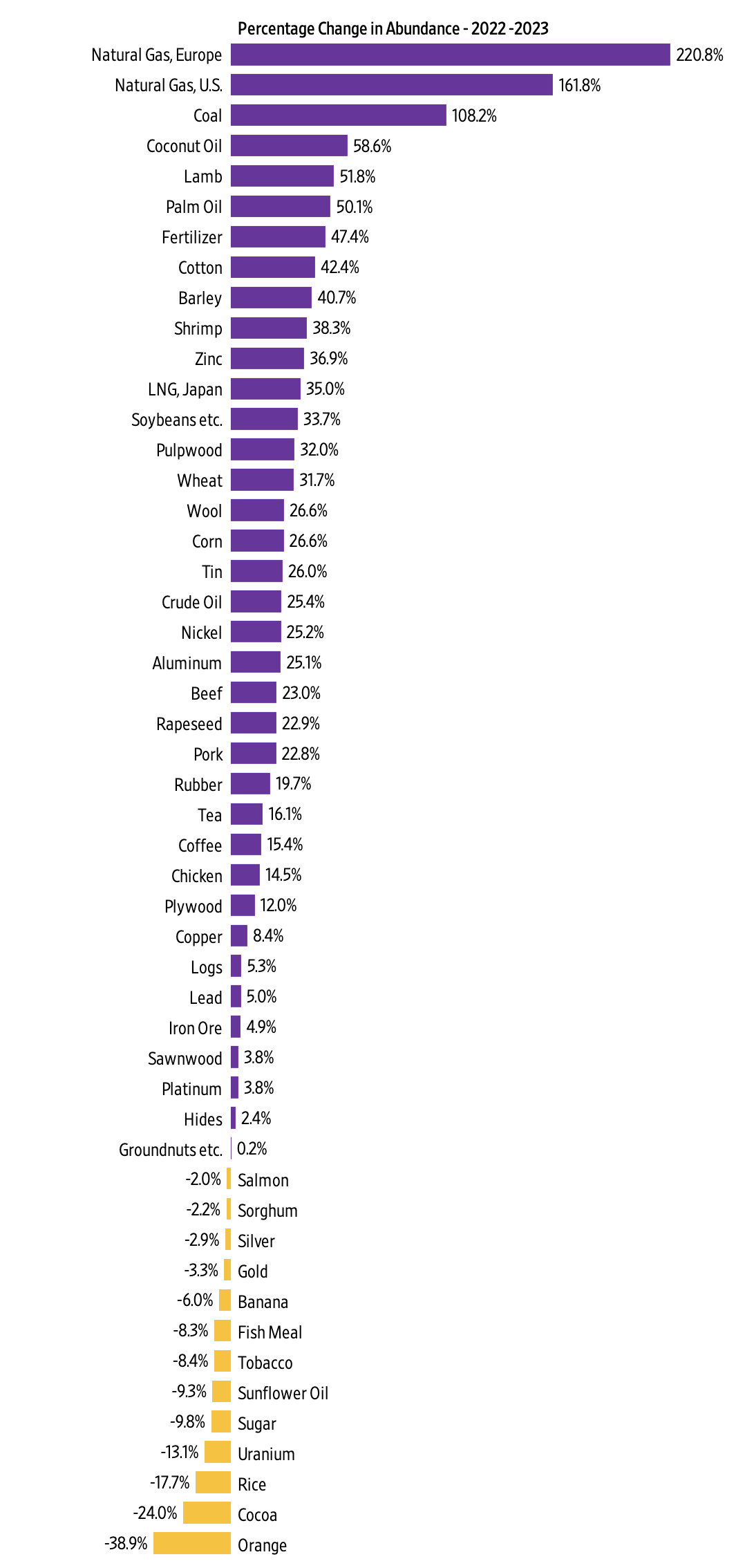

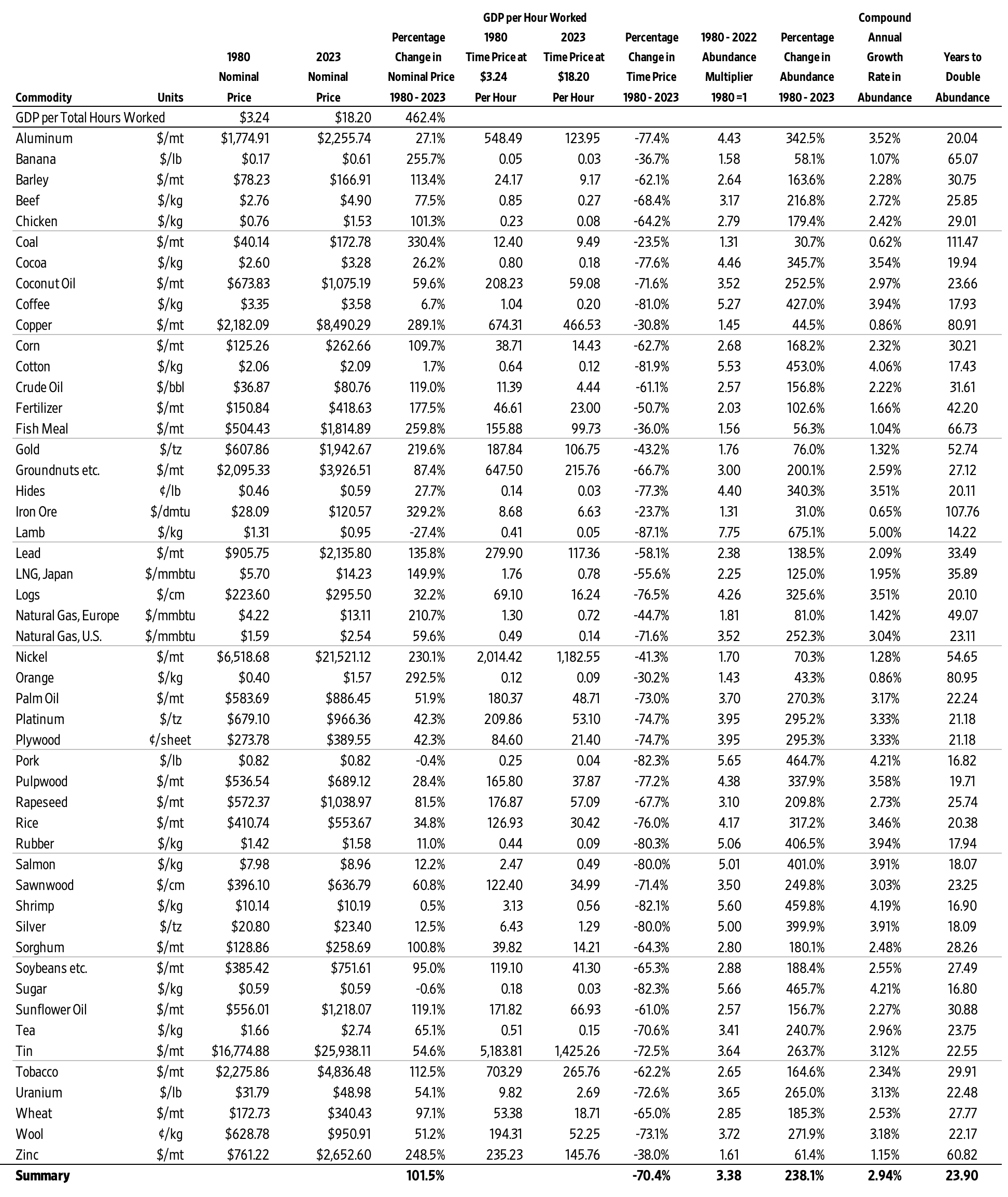

First, prices ought to be compared with income in order fully to understand changes in abundance. Therefore, we use time prices in our analysis. Time prices are equal to nominal prices divided by nominal hourly compensation. Money prices are expressed in dollars and cents. Time prices are expressed in hours and minutes. For the denominator in our ratios we relied on production or blue-collar hourly compensation as reported by Miami University economist Samuel H. Williamson and University of Illinois at Chicago economist Lawrence H. Officer who run the well-known economic history website measuringworth.com. Their data series relies on the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and other sources.

When analysed with time prices, Simon wins the bet 54.2 per cent of the time. The average return over this 110-year range also favours Simon (2.22 per cent).

The “War Clause”

The original Simon–Ehrlich bet included a war clause according to which the agreement would be null and void should the United States be at war on 24 September 1990. The United States last declared war on 8 December 1941. However, military action in Korea and Vietnam, and most recently the War on Terror, should be interpreted as “wars” (see Doe v. Bush, 2003). From 1910 to 2019, the US was at war in 37 years, or 33.6 per cent of the time. If we remove the years for World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the War on Terror, we end up with 73 ten-year bets to analyse. Simon would win those bets 69.9 per cent of the time with a return of 18.0 per cent.

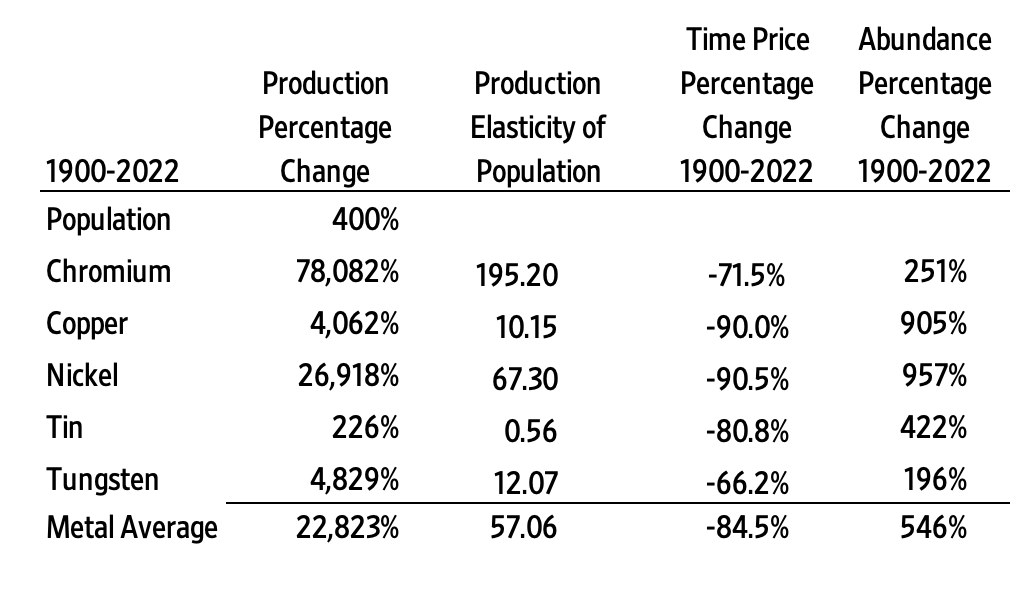

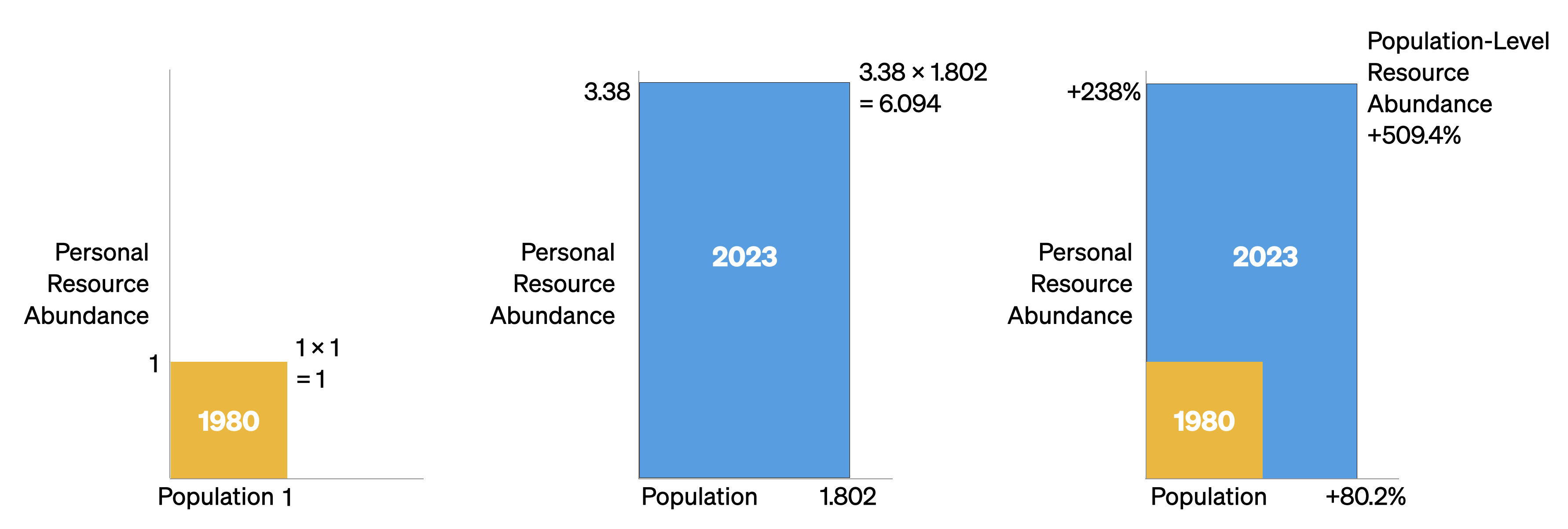

Overall Index and Population

Even more important than the change in the time price of the five-metal basket between 1900 and 2019 is the relationship between commodity prices and population growth. World population was 1.6 billion in 1900. By 2019, it had increased by six billion, or 375 per cent. Over the same time period, it increased in the United States from 76.2 million to 329 million or 330 per cent.

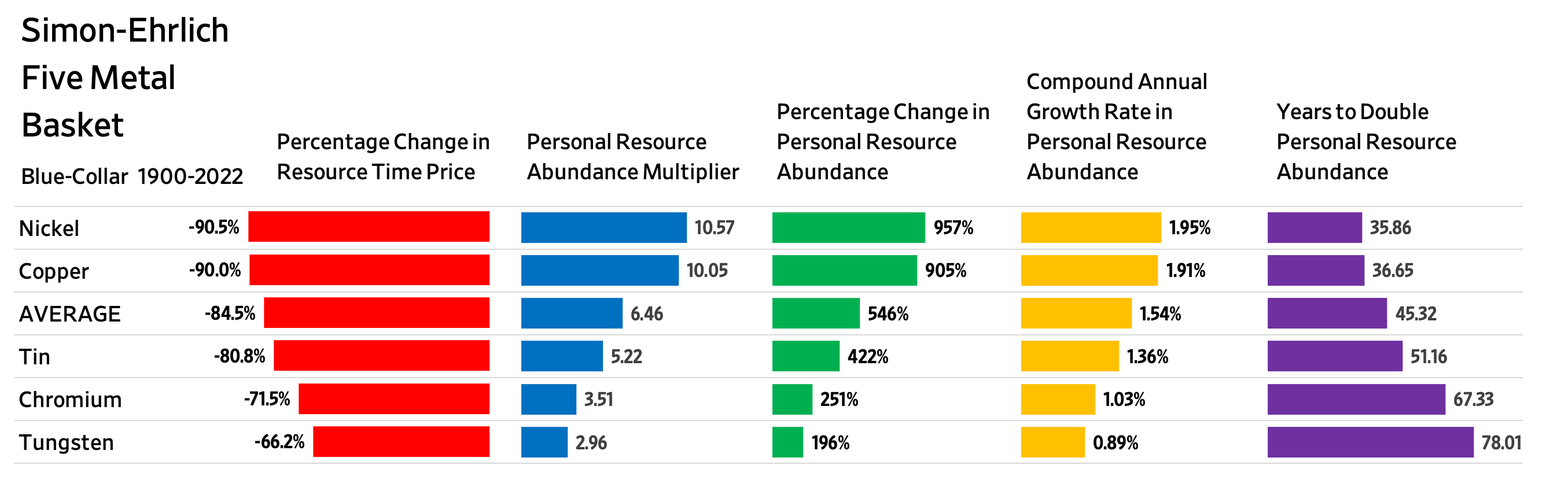

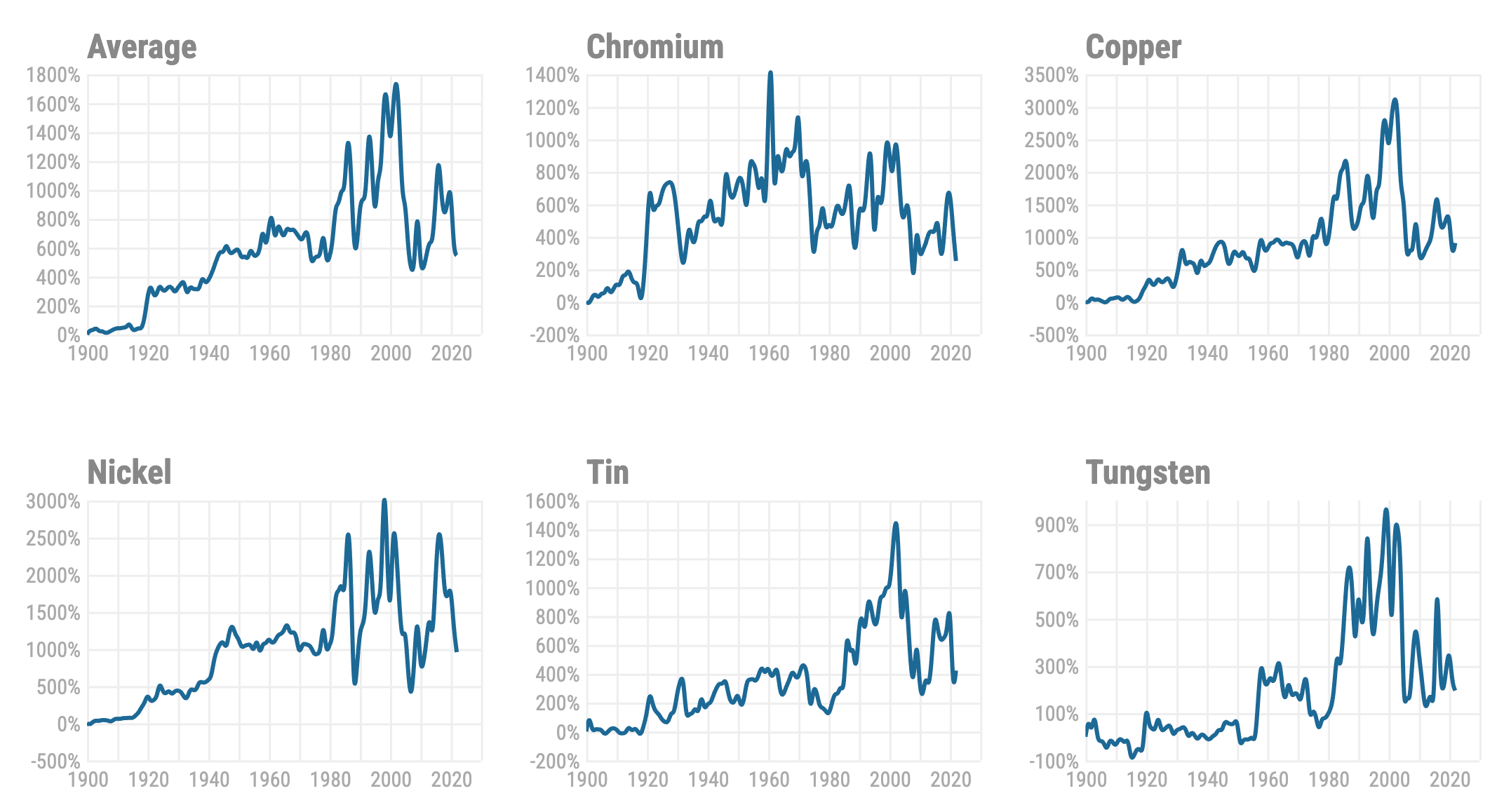

While the nominal prices of the five-metal basket increased 2,909 per cent over this 119-year period, blue-collar hourly income increased by 23,485 per cent. Consequently, the time price of the five-metal basket of commodities index fell by 87.2 per cent – from 100 in 1900 to 12.7 in 2019. The index was above 100 in only five of the 119 years analysed, and for two of those years the United States was involved in World War I.

The real winners of the increase in resource abundance are ordinary people. For blue-collar workers, the time required to earn enough money to buy one basket of five metals in 1900 buys 7.84 baskets today. Overall abundance of the five metals increased 684 per cent, indicating a compound annual growth rate of 1.75 per cent between 1900 and 2019. Unskilled workers enjoyed a significant increase in abundance as well. The time required to earn enough money to buy one basket of five metals in 1900 buys 4.86 baskets today. That indicates a 386 per cent increase in abundance and a compound annual growth rate of 1.34 per cent.

Conclusion

The Simon–Ehrlich bet provides academics with plenty to argue over, but the larger trend is unambiguous – resources are becoming more, not less, abundant in relation to the labour time it takes to “buy” them. The period since 1900 has been marked by world wars, famines and depressions. Yet population grew at an average rate of 1.33 per cent per year and the five-metal basket of commodities grew more abundant at an average rate of 1.75 per cent per year. Adding the increase in population and the increase in abundance indicates a combined rate of around 3.08 per cent, indicating a doubling of abundance every 23 years. These figures are a salutary reminder to those who, like Paul Ehrlich, see resource constraints as limiting economic progress.

References

Ehrlich, P. (1968). The Population Bomb. Cutchogue, NY: Buccaneer Books.

Kiel, K., Matheson, V., & Golembiewski, K. (2009). Luck or Skill? An Examination of the Ehrlich–Simon Bet. Faculty Research Series, Paper No. 09-08. Worcester, MA: Department of Economics, College of the Holy Cross.

McClintick, D. & Emmett, R. (2005). Betting on the wealth of nature: The Simon–Ehrlich wager. PERC Reports, 23(3), 16–17.

McCusker, J. J. (2001). How Much Is That In Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (2nd ed.). Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society.

Perry, M. (2008). Would Julian Simon have won a second bet? Carpe Diem, 13 February. https://mjperry.blogspot.com/2008/02/would-julian-simon-have-won-second-bet.html (accessed 16 November 2019).

Simon, J. (1981). The Ultimate Resource. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Case Cited

Doe v. Bush, 323 F.3d 133. (1st Cir. 2003).

This article was originally published by the Institute of Economic Affairs, and can be found in the Wiley Online Library.