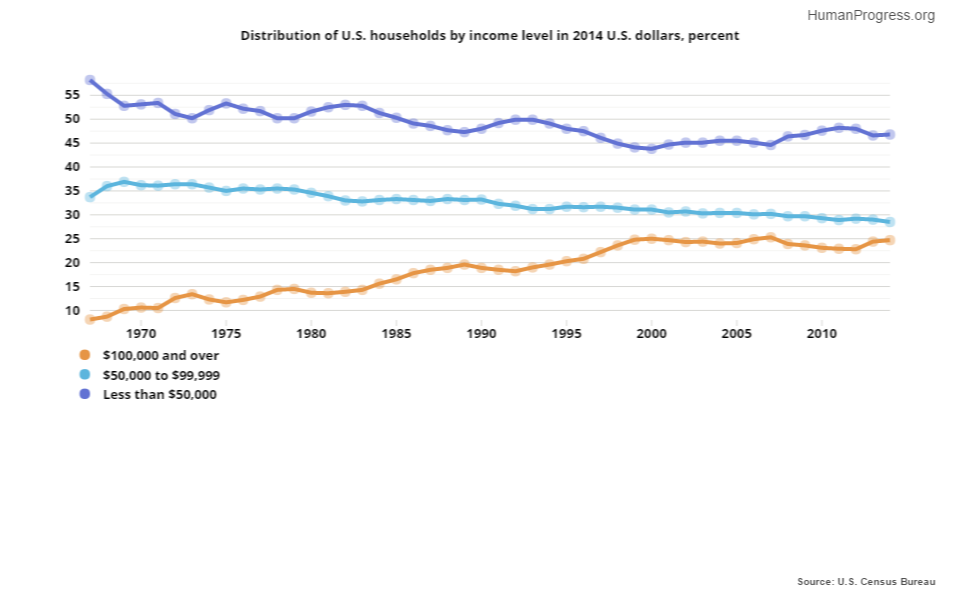

In a recent piece for CapX, my colleague Chelsea Follett wrote about the declining rates of absolute poverty. This data is, indeed, encouraging, but rising income is only one way to measure the improving state of humanity – let’s not forget the other indicators.

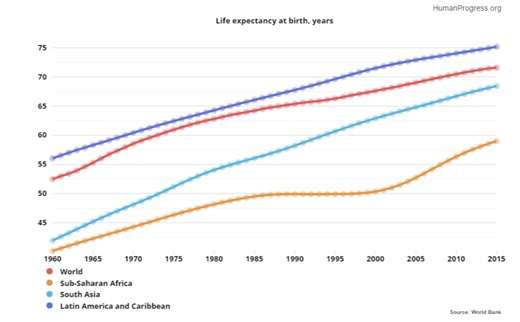

Because when it comes to nutrition, life expectancy, infant and child mortality rates, and education, great progress is being made throughout the world. That is especially true of poor countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, absolute improvements in human well-being are taking place, while the quality-of-life gap with the rest of the world is also being narrowed.

According to the latest data, the share of humanity living on less than $1.90 per person per day, adjusted for purchasing power, shrunk from 42.2 per cent in 1981 to 10.7 percent in 2013 (the last year for which data is available). That’s a reduction of 75 per cent over a comparatively short period of 32 years. According to researchers at the Brookings Institution, “Poverty reduction of this magnitude is unparalleled in history: never before have so many people been lifted out of poverty over such a brief period of time.”

This fall in extreme poverty is all the more remarkable considering that the world’s population rose by 59 per cent over the same time period. Far from being a problem, as was once believed, this growing population has gone hand in hand with increased prosperity. Specialisation and trade, or globalisation, ensured that an increase in the world’s population translated to an increase in the world’s productivity. As such, real average per capita income also rose by 59 per cent between 1981 and 2013.

The greatest reduction in extreme poverty happened in East Asia (from 81 per cent to 3.7 per cent) and South Asia (from 55 per cent to 15 per cent). The data for sub-Saharan Africa is incomplete. In 1990, it is estimated, 54 per cent of people lived there in absolute poverty. Poverty peaked at 59 per cent in 1993. Since then, it has fallen to 41 per cent. So, in terms of absolute poverty reduction, sub-Saharan Africa is a laggard. But, on other measures of human well-being, sub-Saharan Africa outperforms the world average.

The world’s daily calorific intake per person, for example, has increased from an average of 2,550 in 1981 to 2,850 in 2013 – a 12 per cent increase. In sub-Saharan Africa, the caloric intake increased from 2,138 to 2,448 over the same time period. That’s a 15 per cent increase. To put these figures in perspective, the US Department of Agriculture recommends that moderately active adult men consume between 2,200 and 2,800 calories a day and moderately active women consume between 1,800 and 2,000 calories a day.

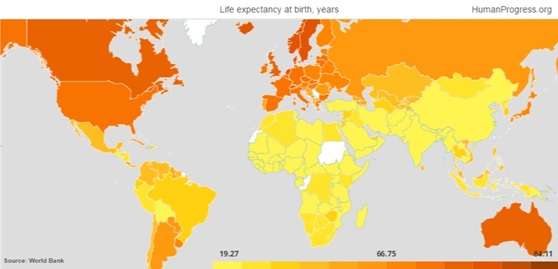

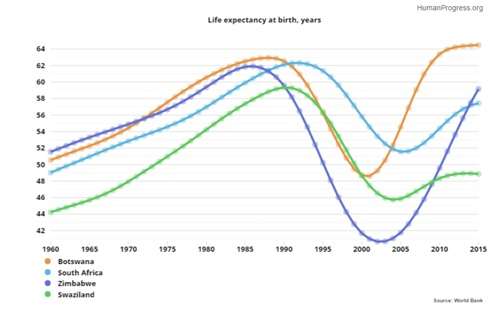

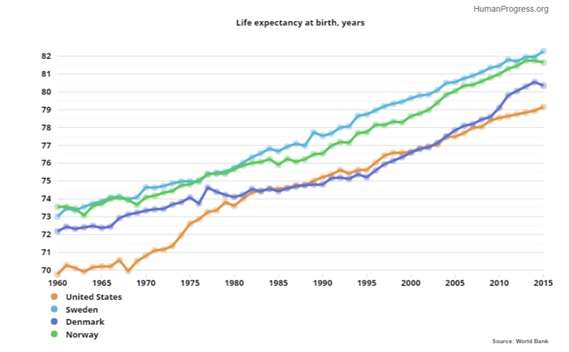

Between 1981 and 2015, global life expectancy rose from 63.2 years to 71.9 years – a remarkable 12 per cent jump that is, undoubtedly, connected to rising incomes and, consequently, improved nutrition. In sub-Saharan Africa, life expectancy rose from 48.5 years to 59.9 years. That’s a 24 per cent improvement (ie, twice the global average). The spread of HIV/AIDS, which threatened to decimate the African population, has been arrested in large part due to the generosity of British and American taxpayers, who subsidise the distribution of anti-retroviral drugs in sub-Saharan Africa.

Let’s now turn to the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals, which measure human progress over a shorter period of time. According to the UN, the infant mortality rate dropped from 64.8 per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 30.5 in 2016. That’s a 53 per cent reduction. In sub-Saharan Africa, it fell from 108 to 53 – a 51 per cent reduction. Over the same time period, the mortality rate for children under five years of age declined from 93.4 per 1,000 to 40.8 per 1,000. That’s a reduction of 56 per cent. But in sub-Saharan Africa, the decline was even more dramatic – from 180 per 1,000 to 78 per 1,000 (ie, 57 per cent).

Enrolment at all education levels is up. Globally, the primary school completion rate rose from 80 per cent in 1981 to 90 per cent in 2015 – a 13 per cent improvement. In sub-Saharan Africa it rose from 55 per cent to 69 per cent over the same time period – a 26 per cent improvement (ie, twice the global average).

The lower secondary school completion rate in the world rose from 53 per cent in 1986 to 77 per cent in 2015 – that’s a 42 per cent increase. In sub-Saharan Africa it rose from 22 per cent to 42 per cent – a 91 per cent improvement (ie, more than twice the global average).

Between 1981 and 2014, the share of the global and sub-Saharan African population enrolled in tertiary educational institutions rose from 13 per cent and 2 per cent to 36 per cent and 9 per cent respectively. Once again, improvement in sub-Saharan Africa was greater (350 per cent ) than was the case with regard to the global average (177 per cent).

October 17 was the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. And, indeed, there was much to celebrate. Absolute poverty has been drastically reduced in much of the developing world. But even in places where absolute poverty persists at unacceptable levels, such as sub-Saharan Africa, much progress is being made in other areas of human well-being. In fact, the world’s poorest region is catching up with the world average at a very fast pace.

This first appeared in Capx.