Marian Tupy, editor of Human Progress, and Professor Gale Pooley from Brigham Young University – Hawaii have used 37 years’ worth of data for 50 foundational commodities covering energy, food, materials, and metals to develop a new framework to measure resource availability. The authors contend that instead of making resources scarcer, population growth has gone hand in hand with greater resource abundance.

The report builds on the famous wager between biologist Paul Ehrlich and economist and Julian Simon on the effect of population growth on the Earth’s resources. While Ehrlich warned that population growth could deplete resources and lead to global catastrophe, Simon saw humans as the “ultimate resource” who could innovate their way out of such shortages. The Ehrlich-Simon wager tracked the real price of a basket of five raw materials between 1980 and 1990, finding as Simon hypothesized, that all measured commodities decreased in price by an average of 57.6 percent, despite a population increase of 873 million.

Tupy and Pooley expand on Simon’s original insight by increasing the basket to 50 commodities and analyzing a longer time period; between 1980 and 2017. Over this time, they find the real price of their basket of commodities decreased by 36.3 percent.

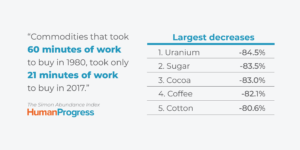

They also introduce a new measure termed “time-price,” the time that an average human must work in order to earn enough money to buy a particular commodity. They find the time-price of their basket of 50 commodities has fallen by 64.7 percent. Put differently, commodities that took 60 minutes of work to buy in 1980 took only 21 minutes of work to purchase in 2017. Should the current trend continue, commodities could become 50 percent cheaper every 26 years.

In addition, the authors develop the concept of price elasticity of population (PEP), which allows them to estimate the effect of population growth on the availability of resources. Over the time period studied the population grew from 4.46 billion to 7.55 billion, a 69.3 percent increase. The PEP indicates that the time-price of the basket of commodities declined by 0.934 percent for every 1 percent of increase in population. Every additional human being born on our planet appears to make resources proportionally more plentiful for the rest of us.

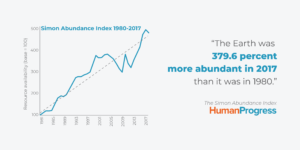

Using the PEP values the authors form the Simon Abundance Framework, which describes progression from decreasing abundance at the one end to increasing abundance at the other end. The authors conclude that humanity is experiencing superabundance with the time-price commodities decreasing at a faster proportional rate than the population is increasing.

Finally, the authors produce the Simon Abundance Index (SAI) that represents the ratio of the change in population over the change in the time-price. Between 1980 and 2017, resource availability increased at a compounded annual growth rate of 4.32 percent, meaning Earth was 379.6 percent more abundant in 2017 than it was in 1980.

Tupy and Pooley forecast that the time-price of commodities could fall a further 29 percent over the next 37 years as humanity continues to make resources more plentiful through greater efficiency of use, increased supply, and the development of cheaper substitutes. They caution, however, that for this trend to continue market incentives and the price mechanism must endure.

“The world is a closed system in the way that a piano is a closed system. The instrument has only 88 notes, but those notes can be played in a nearly infinite variety of ways. The same applies to our planet,” write Tupy and Pooley. “The Earth’s atoms may be fixed, but the possible combinations of those atoms are infinite. What matters, then, is not the physical limits of our planet, but human freedom to experiment and reimagine the use of resources that we have.”

Read the new Policy Analysis, The Simon Abundance Index: A New Way to Measure Availability of Resources