Summary: This article presents a new model for international development based on local knowledge. The author argues that dignity-first development can foster economic growth and institutional innovation, which are essential for spreading liberal democracy. He contrasts this approach with the failed top-down models of the past, which ignored the lessons of the Great Enrichment and provoked resentment and authoritarianism.

The Great Enrichment, which raised living standards by a whopping 3,000 percent since 1800, was not planned from above. It was driven by individuals who, once free, could work to improve their lives and societies.

Unfortunately, this insight is lost on the international development community, which continues to ignore local knowledge and push outsider-led projects on the developing world. In our new book, my co-author and I present a new model for international development, which combines the lesson of the Great Enrichment with the latest interdisciplinary research and our own experience supporting locally-led change around the world. We call it dignity-first development.

To define dignity, we look to local perspectives. For example, in 2019, the Overseas Development Institute interviewed refugees in Bangladesh and Lebanon to learn what the term dignity meant to them in the context of receiving aid. While interpretations varied slightly across cultures, two aspects stood out: dignity as respect and dignity as self-reliance. One refugee is quoted as saying, “Working hard and earning your own livelihood is a big part of Rohingya identity and our idea of dignity.” In development rhetoric, dignity as respect is the familiar interpretation, while dignity as self-reliance is absent from most models.

Stressing the importance of self-reliance in development is not just a “bootstraps” argument for solving poverty. It’s an argument that when individuals participate freely in the economy, they contribute more than the marginal product of their labor. With dignity and freedom, individuals become active agents whose day-to-day decisions create economic growth and whose knowledge helps craft institutions that favor the free exercise of those decisions.

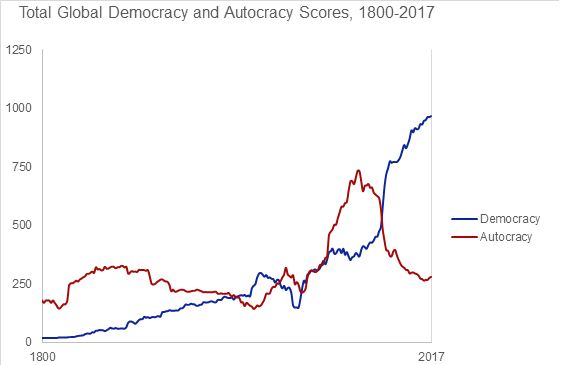

The innovation that enabled the Great Enrichment required what Carl Schramm and Bob Litan refer to as “a process of constant and continual entrepreneurial revolution.” Such a process, we argue, is best served by the ideals of liberal democracy. However, those ideals cannot be spread through what some experts call “isomorphic mimicry” or “cargo cult thinking” – the copycat approach to institution building. Real institutional change is idiosyncratic both in the process of change and in the outcome. After all, those who will be governed by the new institutions – who will either be oppressed or set free by them – are in the best position, both morally and practically, to build them.

In this way, dignity means self-determination at the individual and institutional levels of development. Liberal institutions are not the West’s gift to the rest. We have tried that approach, and the result has been a rise in authoritarian populism, not as a preferred ideology to liberalism, but as an expression of resentment towards outsiders whose ill-fit institutional models failed to function as promised.

The global development community is now trying to fix the mess it created by practicing “localization,” an attempt to limit the influence of outsiders by supporting local NGOs. Rhetorically, this is a step in the right direction, but in practice, unsurprisingly, outsider influence remains outsized. In 2021, USAID, which has new targets for increasing the proportion of its funding to local NGOs, earned unflattering media coverage for its failure to attract local partners in Central America after U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris promised to investigate the “root causes” of migration.

Localization must be about more than who gets the money. It must be about who leads development. We offer the following three guidelines for getting localization right.

First, projects, strategies, and definitions of success must come from local NGOs. Outside experts must restrain their impulse to “solve” problems for others. They must accept their limitations and give up on setting priorities and designing and leading projects. Instead, local NGOs must present themselves along with their vision for change and compete for support.

Second, award amounts must be proportional to the project. Predetermined development budgets are often too large and represent too much of an NGO’s total budget. Single-donor projects and/or single-donor NGOs struggle to maintain independence and often fail to diversify their funding sources, creating organizational volatility.

Third, accountability still matters. While local organizations should define success, grant makers should only fund organizations with ambitious, measurable, and meaningful goals. Subsequent funding should be contingent on a combination of achievements promised and authentic learning from shortfalls that can inform future work.

Government-funded aid agencies may be structurally incompatible with true localization. In that case, private philanthropy would lead this new model. But regardless of where the money comes from, all outsiders must take human dignity seriously and understand its fundamental role in economic development and the future of liberal democracy.