Today marks the 52nd installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. The 51st installment was about Frederick McKinley Jones.

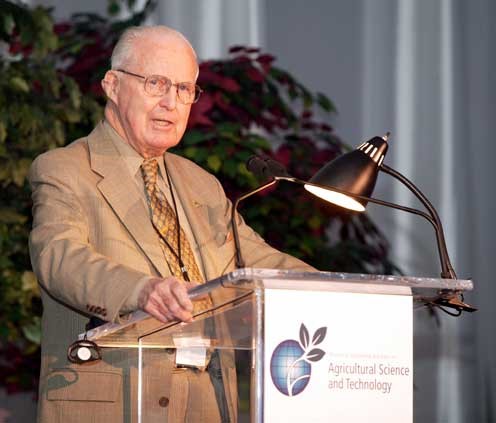

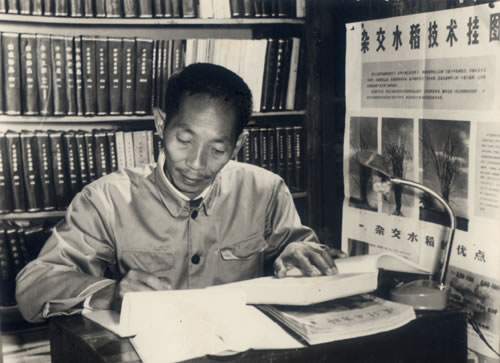

This week our hero is Yuan Longping, a Chinese agronomist dubbed “the father of hybrid rice.” In the early 1970s, Yuan developed the first variant of high-yield hybrid rice. Yuan’s discoveries, coupled with breakthroughs in wheat hybridization in the 1950s and 1960s by our first Hero of Progress, Norman Borlaug, helped usher in the Green Revolution, which reduced the likelihood of famine in most of the world. As rice is the staple food for approximately half the world’s population, by increasing the plant’s yield, Yuan’s work helped save millions of lives. By the late 1990s, the excess yield brought about by Yuan’s hybrid rice fed an additional 100 million Chinese people each year. Today, varieties of Yuan’s rice are grown in more than 60 countries worldwide.

Yuan was born on September 7, 1930, in Beiping, as Beijing was called at the time. The Chinese Civil War (1927–1949), the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), and the associated economic turmoil forced Yuan’s family to move extensively around southern China during his early life. Despite the disruptive upbringing, as both of Yuan’s parents were teachers, he and his five siblings received a good education.

In 1949, Yuan finished high school and began studying at the Southwest Agricultural College (now called Southwest University) on the outskirts of Chongqing in Sichuan province. Yuan’s enrollment in college coincided with the victory of the Communist Party of China in the civil war and the party’s consolidation of power across the country. Unfortunately for Yuan, who chose to major in agronomy with a specific focus on crop genetics, the new Chinese leadership presented a problem.

In the early 1950s, there were two primary theories of heredity. The first theory, based on the work of Soviet agronomists such as Ivan Vladimirovich Michurin and Trofim Lysenko, rejected modern genetics and proposed that organisms change over the course of their lives to adapt to altering environmental conditions. Champions of this idea claimed that by modifying a crop’s environmental conditions (such as temperature, exposure to ultraviolet rays, and soil conditions), they could induce positive changes that would be inherited by the plant’s offspring, eventually producing higher yields.

The other theory of heredity came from Western scientists such as Gregor Mendel (often dubbed “the father of genetics”) and Thomas Hunt Morgan. They believed that understanding genes was essential to understanding heredity. Mendel and Morgan proposed that while a set of genes are specific to each species, variations between individuals of the same species are heritable (meaning they are passed down from parents to their offspring) and occur due to the form each gene takes.

At the time, the Chinese government looked to the Soviet Union for nearly all scientific and technological insight. As such, the Soviet theory of heredity was considered the “truth” in China. Anyone championing alternative scientific ideas could find themselves accused of spreading misinformation and branded as an “enemy of the state.”

At college, Yuan was officially taught the theory of heredity championed by the Soviets. However, outside of class, one of his professors, Guan Xianghuan, who rejected Soviet dogma, privately taught Yuan Western scientific theories. Guan encouraged Yuan to carry out experiments to test both Soviet and Western ideas. While exposure to the Western ideas of heredity served Yuan well for his future career, a few years after mentoring Yuan, Guan was labeled an enemy of the Communist Party for his “Western views.” After years of harassment from the government, Guan took his own life in 1966.

In 1953, Yuan graduated from college and was assigned to teach crop cultivation, breeding, genetics, and Russian at Anjiang Agricultural School, a small college in rural Hunan. During this time, Yuan conducted experiments to modify crops using the Russian theories of heredity. However, when these proved unsuccessful, he secretly read Western scientific magazines on crop science and changed his experiments to test Western methods.

In the late 1950s, Yuan’s work on crop genetics and breeding became far more urgent. Between 1958 and 1960, because of Mao Zedong’s (the leader of the Communist Party) so-called Great Leap Forward—which, among other things, saw the government collectivize agriculture—China was plunged into the worst famine of modern times. Nationwide, tens of millions were dying from starvation, and as Yuan was living in the Hunan countryside, he saw the impact of the famine firsthand.

Yuan saw the bodies of several people who had died from starvation on roadsides. Later in life, Yuan recalled, “There was nothing in the field because hungry people took away all the edible things they could find.” He continued, “Famished, you would eat whatever there was to eat, even grassroots or tree bark. . . . I became even more determined to solve the problem of how to increase food production so that ordinary people would not starve.”

After two years of studying sweet potatoes, in 1960, Yuan switched to researching how to modify rice to create higher-yielding variants. According to Yuan, he switched to rice because rice was the staple food of China and because the government was more likely to support and fund rice research.

In the West, the hybridization of wheat and maize led to tremendous food production breakthroughs and helped feed millions of people. Hybridization of crops means crossbreeding genetically dissimilar crops to produce offspring. Thanks to a process known as heterosis, a hybrid plant is usually more productive and can exhibit greater biomass, growth, or fertility than either parent plant. However, because rice is a self-pollinating plant, most scientists believed rice hybridization and heterosis was impossible.

In 1961, Yuan searched rice fields for months and eventually found what he considered an “outstanding” rice plant with large panicles and full grains. Yuan meticulously collected more than a thousand seeds of this “outstanding” rice and planted them the following year. To Yuan’s shock, the good traits of the parent crop were not passed down to the next generation.

As heterosis is only obvious in the first generation of hybrid crops, after careful analysis, Yuan concluded that this “outstanding” rice was a natural hybrid. This discovery meant that, contrary to the prevailing wisdom at the time, rice could be hybridized.

Despite this important discovery, one of the largest problems facing Yuan was that hybridization requires different male and female plants as parents. As rice is self-pollinating, if the male parts of the rice plant were removed, crossbreeding and hybridization could occur when the remaining female parts accepted foreign pollen from other rice varieties. Unfortunately for Yuan, the time-consuming and delicate process of removing the male parts of the rice plant made that process impractical on a large scale. This predicament led Yuan to hypothesize that if he and his team could find a strain of naturally mutated male-sterile rice (i.e., rice with female parts only), then those plants could be used to hybridize new rice varieties.

In 1964, Yuan and a student spent the summer searching rice fields for these elusive naturally mutated male-sterile rice plants. In a 1966 article in the Chinese Science Bulletin, Yuan reported that he found six individual rice crops that had the potential for hybridization.

Unbeknownst to Yuan, this 1966 publication likely saved his life. At the time, the Cultural Revolution was in full force across China. Posters denouncing Yuan as a counter-revolutionary began appearing across his university, and local officials made plans to imprison him. The state even reserved a spot for him in the “cowshed,” a place in the local prison for dissenting intellectuals. Fortunately, upon reading his publication about naturally mutated male-sterile rice, the director of the national science and technology commission and other provincial and national leaders sent a letter of support to the college in favor of Yuan’s work. Following the letter, Yuan was allowed to continue his work and was even provided greater financial support.

Despite having the six naturally mutated male-sterile rice plants that he wrote about in his 1966 article, Yuan discovered that when these female parts-only plants were hybridized using pollen from other rice strains, their male-sterile traits were not passed down to their offspring. If Yuan couldn’t find a way to ensure that the offspring of the hybridized rice passed on only female parts (i.e., it was male-sterile), it would make widespread hybridization extremely impractical. Given that, Yuan and his team began searching for wild varieties of male-sterile rice, which Yuan thought may exhibit more promising genetical material.

In 1970, beside a railway line in Hainan, at long last, Yuan discovered a male-sterile wild rice plant that scientists refer to as “wild abortive.” Soon after this discovery, Yuan published a paper that outlined how the genetic material from the male-sterile wild rice could potentially be transferred into commercial rice strains. Yuan hypothesized that if that were to happen, the plant’s offspring would still be male-sterile and that the world’s heavily inbred commercial rice strains could be hybridized to produce greater yields.

In 1973, Yuan began harvesting the offspring of the “wild abortive” rice. To Yuan’s delight, the offspring was comprised of tens of thousands of male-sterile rice plants. By the late 1970s, Yuan’s hybrid rice had yields 20–30 percent higher than traditional commercial varieties.

The discovery of high-yield hybrid rice helped to alleviate food insecurity not only in China but in countries across the world. In doing so, Yuan’s rice saved millions of lives.

Throughout the 1980s, Yuan donated his key rice varieties to various domestic and international agronomists and organizations. He and his team trained farmers and introduced his hybrid strains in more than 80 countries worldwide.

By 1991, the United Nations found that 20 percent of the world’s rice output came from the 10 percent of the world’s rice fields that grew Yuan’s hybrid rice. In 1999, it was found that in China alone, the production increases brought about by hybrid rice fed an additional 100 million people each year. Today, a fifth of all rice grown globally originates from Yuan’s hybrids.

Later in life, Yuan became somewhat of a national celebrity in China and was praised extensively by the ruling Communist Party. However, quite unusually for someone of his prominence, he never engaged in politics nor joined the Communist Party.

Yuan was awarded dozens of national and international awards. In 2000, he was awarded the UNESCO Prize for Science, and in 2004, he was awarded the World Food Prize. Four asteroids, a minor planet, and a college in China are named after him.

Throughout his life, Yuan continued to work to make his hybrid varieties even more productive. These advancements included crossbreeding rice with maize to be more nutritious and enriching rice with Vitamin A to help improve people’s eyes. Even as late as 2018, at the age of 87, Yuan and his team created a hybrid rice variety that could grow in salt-rich soil, which helps farmers living near the coast. Yuan died on May 22, 2021, in Changsha, Hunan. In the days following his death, thousands of mourners put flowers and bowls of boiled rice outside the funeral home.

By developing the first variant of high-yield hybrid rice, Yuan’s work has improved the world’s food stability. Despite fierce political resistance early in his career and critics who believed that rice hybridization was impossible, Yuan persevered and proved the naysayers wrong. As a result, he has saved millions of lives, and millions of people eat Yuan’s hybrid rice every day. For these reasons, Yuan Longping is our 52nd Hero of Progress.