Today is the fifth installment of a new series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled, The Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to unsung heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the wellbeing of humanity. You can find the 4th part of this series here.

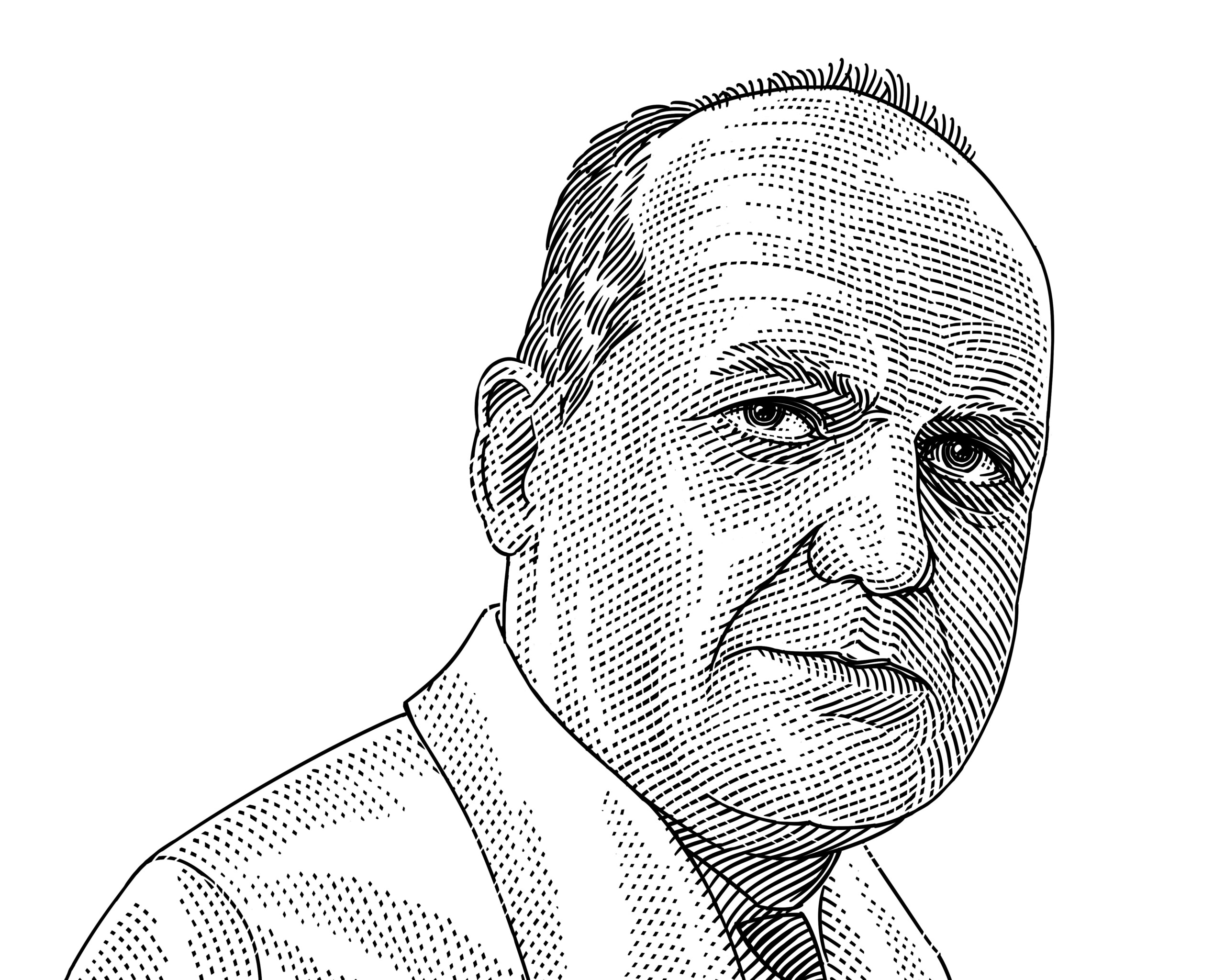

Our fifth Hero of Progress is Jonas Salk, the man who pioneered the world’s first effective polio vaccine.

Polio is a highly infectious viral disease that is most often transmitted by drinking water that has been contaminated with the feces of someone carrying the virus. The virus spreads easily in regions with poor sanitation. The symptoms include: fever, fatigue, headache, vomiting, stiffness and pain in the limbs. Most infected patients recover. In one out of two-hundred cases, the virus attacks the nervous system, leading to irreversible paralysis. Of those paralyzed, between 5 and 10 percent die when their breathing muscles become immobilized.

Polio has a relatively long incubation period – it can spread for many months without being detected – making it extremely difficult to monitor. According to Max Roser from Oxford University, “Up to the 19th century, populations experienced only relatively small outbreaks [of polio]. This changed around the beginning of the 20th century. Major epidemics occurred in Norway and Sweden around 1905 and later also in the United States.”

The first major outbreak of polio happened in the United States in 1916, when the disease infected 27,000 people and killed more than 7,000 people. The second major outbreak of polio in 20th century America happened in the 1950s. It is here Jonas Salk enters our story.

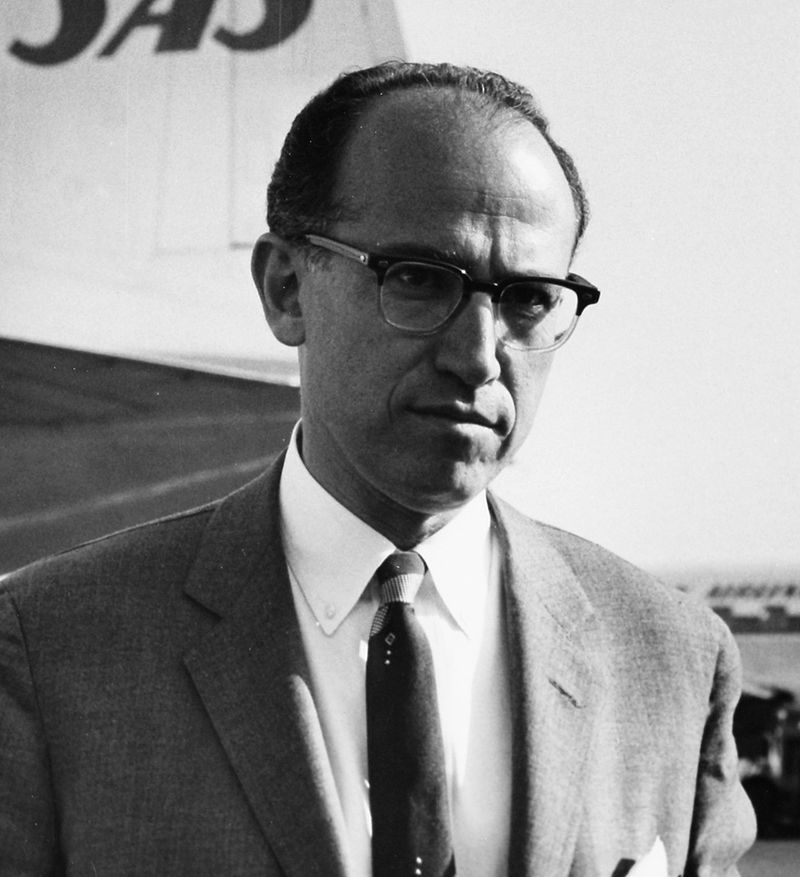

Jonas Edward Salk was born on October 28, 1914, in New York. Salk became passionate about biochemistry and bacteriology during his time at the New York University School of Medicine. After he graduated in 1939, he started working at the prestigious Mount Sinai Hospital. Salk’s focus shifted to researching polio vaccinations in 1948, when he was head-hunted to work at the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis – an organization that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, himself a polio sufferer, helped to set up.

After a large outbreak of polio across the United States in 1952, donations began pouring in to the foundation and in the spring of 1953, Salk put forward a promising anti-polio vaccine. The foundation quickly began trials on 1.83 million children across the United States. These children became known as the “polio pioneers.” Salk’s foundation received donations from two-thirds of the American population and a poll even suggested that more Americans knew about these field trails than knew the then-president’s full name (Dwight David Eisenhower).

On April 12, 1955, Salk’s supervisor, Thomas Francis, announced that Salk’s vaccine was safe and effective in preventing polio. Just two hours later, the U.S. Public Health Service issued a production license for the vaccine and a national immunization program began.

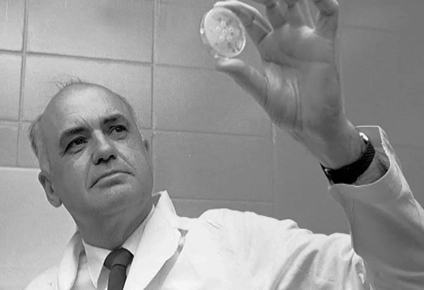

Shortly thereafter, Dr. Albert Sabin, a Polish American medical researcher working at the National Institutes of Health, introduced a polio vaccine that could be administered orally, thereby making vaccination efforts less expensive as trained health workers weren’t needed to administer injections. From a record 58,000 cases in 1952, the United States was declared polio free in 1979.

In 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was founded to administer the vaccine worldwide. When the GPEI began its efforts, polio paralyzed 10 children for life every 15 minutes, across 125 countries. Since 1988, more than 2.5 billion children have been immunized and incidents of polio infections have fallen by more than 99.99 percent. That is, they fell from 350,000 annual cases, to just 22 new cases across 3 countries in 2017. Next year, Africa is due to be declared free of polio – that is, if no new cases are found in Nigeria, which is the last country in the region to report new polio infections.

Following his discovery of the vaccine, Salk received dozens of awards, a presidential citation, four honorary degrees, half a dozen foreign decorations, and letters from thousands of thankful fellow citizens. In 1963, Salk established the Jonas Salk Institute for Biological Studies – a world-class research facility that focuses on molecular biology and genetics, neurosciences, and plant biology. Salk devoted his later years to researching a vaccine for HIV/AIDS. He died on June 23rd, 1995.

Salk’s work has saved hundreds of millions of people from crippling paralysis, and millions from death. Thanks to his vaccine, a disease that has plagued humanity since pharaonic Egypt is almost completely eradicated, and within a few years, the disease will (hopefully) be consigned to history. It is for this reason Jonas Salk deserves to be our fifth Hero of Progress.