Today marks the 43rd installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 42nd part of this series here.

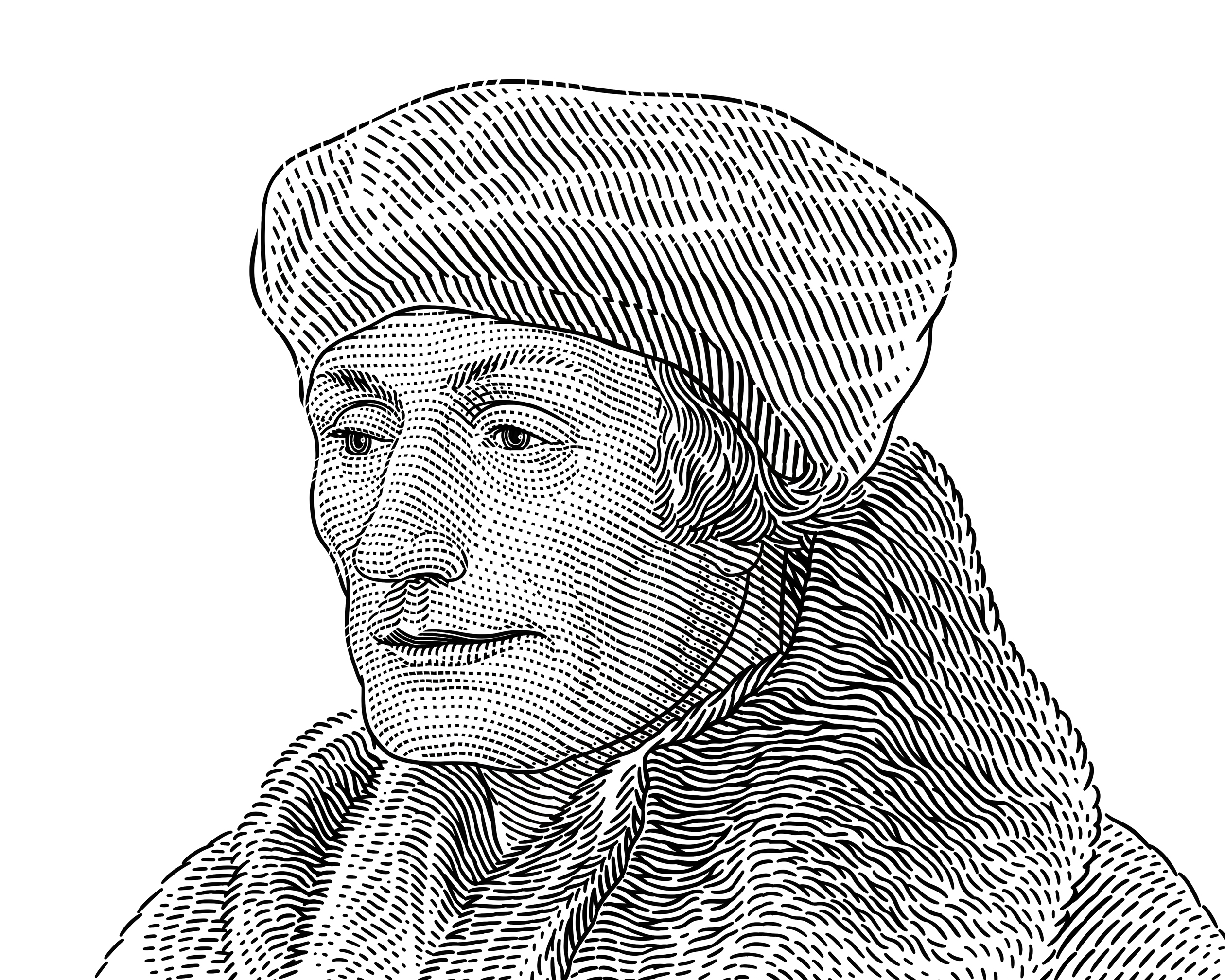

This week, our hero is Desiderius Erasmus, a 16th century philosopher who is widely considered to be one of the greatest scholars of the Northern Renaissance. During the Protestant Reformation, when religious persecution was common across Europe, Erasmus was the first modern champion of religious toleration and peace. According to historian James Powell, throughout the philosopher’s life, Erasmus “championed reason over superstition, tolerance over persecution and peace over war… [and helped to establish the] intellectual foundations for liberty in the modern world.”

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus was born October 28, 1466 in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The exact year of his birth is unknown, but most scholars agree on 1466. Erasmus was the second illegitimate son of Roger Gerard, a catholic priest, and Margaretha Rogerius. Little is known of Erasmus’s mother, but it is thought that she may have been Roger’s housekeeper. Erasmus was educated at several monastic schools and, at the age of nine, he was sent to one of the top Latin schools in the Netherlands, in Deventer.

As a child, Erasmus witnessed a lot of religious violence. At just eight years old, he saw over 200 war prisoners pulled apart on the rack following the order of a local bishop. Erasmus’s early exposure to religious-based violence undoubtedly influenced his future beliefs.

During his time in Deventer, Erasmus began to despise the harsh rules and strict methods used by his religious educators. He would later write that the severe discipline was intended to teach humility by breaking a boy’s spirit. Erasmus’s education in Deventer ended in 1483, when both of his parents died from the bubonic plague.

In about 1485, Erasmus and his brother were living in severe poverty and, out of desperation, they both entered monasteries. Erasmus became a canon regular of the St. Augustine canonry in the small Dutch village of Stein. During his seven years in Stein, Erasmus spent much of his time in the library, where he studied philosophy. He was especially interested in the works of Cicero and other Roman thinkers. After his superiors became unsupportive of his classical studies, Erasmus became increasingly eager to leave the canonry.

Erasmus was ordained as a Catholic priest in April 1492. Soon after that, he left the canonry to become secretary to the Bishop of Cambrai, who had heard of Erasmus’s skill in Latin. In 1495, Erasmus began studying theology at the University of Paris, but grew to dislike the quasi-monastic regimen of his college.

To support his studies, Erasmus began teaching and one of his students, Sir William Blount, invited Erasmus to England in 1499. Erasmus’s time in England was fruitful. He befriended many prominent intellectuals and began teaching at the University of Oxford. Over the next 15 years, Erasmus lived in and traveled to many places including France, England, Belgium and Basel. In 1509, Erasmus graduated with a Doctor of Divinity from Turin University, and between 1509 and 1514 he worked at the University of Cambridge. However, as a man who was frequently in poor health, Erasmus complained that Cambridge could not supply him with enough decent wine (at the time, wine was the medicine for gallstones, from which Erasmus suffered.)

In 1500, Erasmus compiled and translated 818 Latin and Greek proverbs, into a volume called Collectanea Adagiorum. The publication of this work was the first of Erasmus’s many efforts to end the monopoly of learning that was held by the clergy. Throughout his life, Erasmus continued to expand this book. By the time of his death in 1536, he had translated more than 4,151 entries. Many common phrases used today are owed to Erasmus’s translation, including “one step at a time,” “one to one,” and “to sleep on it.”

As Erasmus created more editions of Adagia (as the work later came to be known), he added more commentary that advocated against the violence of the rulers and against preachers who supported wars for their own self-interest. In one passage, Erasmus noted, “do we not see that noble cities are erected by the people and destroyed by princes? … That good laws are enacted by representatives of the people and violated by kings? That the commons love peace and the monarchs foment war?”

In 1513, following the death of the “Warrior Pope” Julius II, Erasmus wrote a short satire denouncing the Pope’s violence. Erasmus implied Julius would not get into heaven, because the Pope spent too much time at war, rather than reading the Gospels. In 1514, Erasmus published Familiarium colloquiorum formulae, often referred to simply as Colloquies.

In Colloquies, Erasmus ridiculed greedy clergymen, rituals that he saw as meaningless and declared marriage to be preferable to celibacy. Rulers in France, Spain, the Netherlands, Austria, and much of Italy decreed that anybody seen with a copy of Colloquies would be executed. Despite these harsh laws, more than 24,000 copies of Colloquies were sold during Erasmus’s lifetime. According to John Dalberg-Acton, a 19th century Italian historian, it was “the most popular book of its age.”

In a later edition of Adagia, which was released in 1515, Erasmus also took aim at the training of preachers and argued that priests should be trained in the “philosophy of Christ,” rather than on different scholastic subjects. Erasmus later argued that “if the Gospel were truly preached, the Christian people would be spared many wars.”

In 1516, because of all the translation errors in the official Latin Vulgate edition of the Bible, Erasmus used Greek manuscripts to produce a new and more accurate translation of the New Testament. Erasmus’s work inspired many other individuals to translate the bible into different languages and within 20 years there were German, English, Hungarian and Spanish translations. Very few people could read Latin, so these new translations helped to make the Bible more accessible to people across Europe. The people no longer had to rely on their preacher’s interpretation of the Latin Bible and could learn about their religion on their own.

In the following years, Erasmus released a series of works making the case for peace and arguing that salvation was not achieved by performing religious rituals, but by cultivating faith and goodness. Contrary to many thinkers of his day, Erasmus also argued against colonialism, and for a “limited monarchy, checked and decreased by an aristocracy and by democracy.”

Erasmus considered himself an impartial party during the Protestant Reformation, criticizing both the Catholic church hierarchy and the Protestant reformers. He remained a Catholic, committed to reforming the church from within. Throughout his life, Erasmus had many arguments with Martin Luther, a leading Protestant figure of the day.

Erasmus argued that Luther was an enemy of liberty and that he was on the side of the tyrannical rulers, rather than the people. Toward the end of his life, Erasmus warned that religious wars could soon breakout in Europe. In one of his last works, On the Sweet Concord of the Church, Erasmus made one final plea for Catholics and Protestants to “tolerate one another.” Erasmus died a painful death on July 11, 1536 in Basel, Switzerland, following a three-week struggle with dysentery. He was buried in Basel cathedral.

Unfortunately for the people of Europe, Erasmus’s predictions of impending religious wars came true, and in the decades after his death, Europe was embroiled in religious violence that saw hundreds of thousands of Catholics and Protestants die. However, a couple of hundred years after his death, a newfound appreciation for Erasmus’s work emerged among Enlightenment scholars. The French dramatist and encyclopaedist Denis Diderot, for example, noted that “we are indebted to him, principally for the rebirth of the sciences, criticism and the taste for antiquity.”

Throughout his life, Erasmus was offered reputable positions in academic institutions across Europe, but he declined them all, preferring a life as an independent scholar dedicated to writing works that would help societal progress. Although Erasmus’s works failed to prevent the religious wars, his writings went on to have enormous influence on the Enlightenment era’s ideas of rationality, peace and liberty. He is often credited with being the most influential figure of the Northern Renaissance and the first modern champion of toleration and peace. For these reasons, Desiderius Erasmus is our 43rd Hero of Progress.