Today marks the 34th installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 33rd part of this series here.

This week, our hero is Alan Turing – an English mathematician, computer scientist and cryptanalyst, who is best known for his contributions to the field of computer science and for developing a machine that cracked the Nazis’ “Enigma” code during World War II. The Enigma machine was an enciphering device that was used extensively by the Nazi forces in WWII to send messages securely. Turing’s work in creating a machine that could break the encrypted German messages meant that Allied forces had a huge advantage during the war. Some historians have estimated that thanks to Turing’s work, WWII was shortened by at least 2 to 3 years. By cutting the war short, Turing’s work likely saved millions of lives.

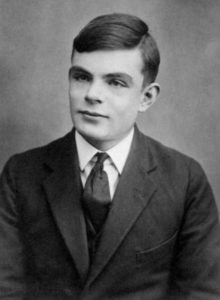

Alan Turing was born on June 23, 1912 in London, United Kingdom. At a young age, Turing displayed signs of high intelligence and after enrolling at Sherborne School at the age of 13, he developed a passion for mathematics and science. In 1931, Turing was accepted to study at the University of Cambridge, and three years later he graduated with first-class honors in mathematics. The University of Cambridge was so impressed with Turing’s work that, aged just 22, he was elected a fellow of King’s College, Cambridge.

In 1936, Turing published a seminal paper “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem” [i.e., decision problem]. In that paper, Turing presented the idea of a universal machine (later called the “Turing machine”) which could solve complex calculations. Many consider Turing’s paper as a foundational work in the field of computer science and artificial intelligence, as it foreshadowed how a modern digital computer could work.

That same year, Turing moved to New Jersey to study for a Ph.D in mathematics at Princeton University. Turing graduated with his Ph.D. in just two years and returned to his fellowship at Cambridge in 1938. A few months later, Turing was asked to join the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) – a British code-breaking organization. With the outbreak of WWII in September 1939, Turing moved to the GCCS’ wartime headquarters at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire.

A few weeks before Britain declared war on Germany, the Polish government gave the British government the details of their work on cracking the German Enigma machine. Although the Polish intelligence had some success in cracking the Enigma code, at the outbreak of the war, the Nazis increased the machine’s security and began to change the cipher daily. That meant that Turing and his team had just 24 hours to crack the Enigma code and translate the content of the messages, before cipher was changed again.

Turing played a key role in creating a machine known as the ‘Bombe.” That device helped to significantly reduce the work involved in cracking the Enigma code and by mid-1940, the Luftwaffe communications were being read at Bletchley Park.

Once the German Air Force communications had been cracked, Turing turned his attention to decrypting the more complex German naval communications. This work was of vital importance because German U-boats were destroying many cargo ships loaded with essential supplies that were sent from North America to Britain. So many supply ships were being destroyed that Churchill’s analysts calculated that Britain would soon be starving.

Thankfully, by 1941, Turing personally cracked the different form of Enigma code that was being used by the German U-boats. With the U-boats revealing their positions in their communications with one another, Allied cargo ships could be diverted away from the “wolfpacks” of Nazi submarines. After WW2, Churchill confessed that “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

Many historians agree that if Turing had not cracked the German Naval Enigma code, the Allied invasion of Europe (i.e., the D-Day landings) would have likely been delayed by at least a year. Any delay in invading mainland Europe would have enabled the Germans to strengthen their coastal defenses and prolong the time it took the Allied forces to reach Berlin.

After the war ended in 1945, Turing was awarded an OBE (Order of the British Empire) for his services to the country and he moved to London to work for the National Physical Laboratory. During his time in London, Turing led the design work on the “Automatic Computing Engine,” the world’s first stored-program computer. Although the complete version of Turing’s design was never built, the adapted concept significantly influenced the design of the English Electric DUECE and the American Bendix G-15 – the world’s first personal computers.

In 1952, Turing was prosecuted for homosexual acts after the police discovered that he had been in a sexual relationship with a man. To avoid prison, Turing agreed to undergo chemical castration through a series of synthetic estrogen injections. As a result of his conviction, Turing’s security clearance was revoked, and he was barred from continuing his work with cryptography at GCCS, which had become Government Communications Headquarters or GCHQ in 1946.

Angered by being shunned from the field that he had revolutionized, Turing committed suicide in 1954, aged 41. The immense legacy of Turing’s life did not fully come to light until the 1970s, when the secret work done at Bletchley Park was declassified.

Turing’s impact on computer science is celebrated by the annual “Turing Award,” which is the highest accolade in the field of computing. In 1999, Time magazine named Turing as one of the “100 Most Important People of the 20th Century.”

In December 2013, Queen Elizabeth II formally pardoned Turing. In January 2017, the British government enacted “Turing’s Law,” which posthumously pardoned thousands of gay and bisexual men who were convicted under historic legislation that outlawed homosexual acts.

Turing is often considered the “Father of Computer Science” for his work in conceptualizing the world’s first personal computer. If that achievement weren’t enough, Turing’s contribution to cracking the German Enigma code at Bletchley Park is also credited with shortening WWII by several years, which saved millions of lives. For those reasons, Alan Turing is deservedly our 34th Hero of Progress.