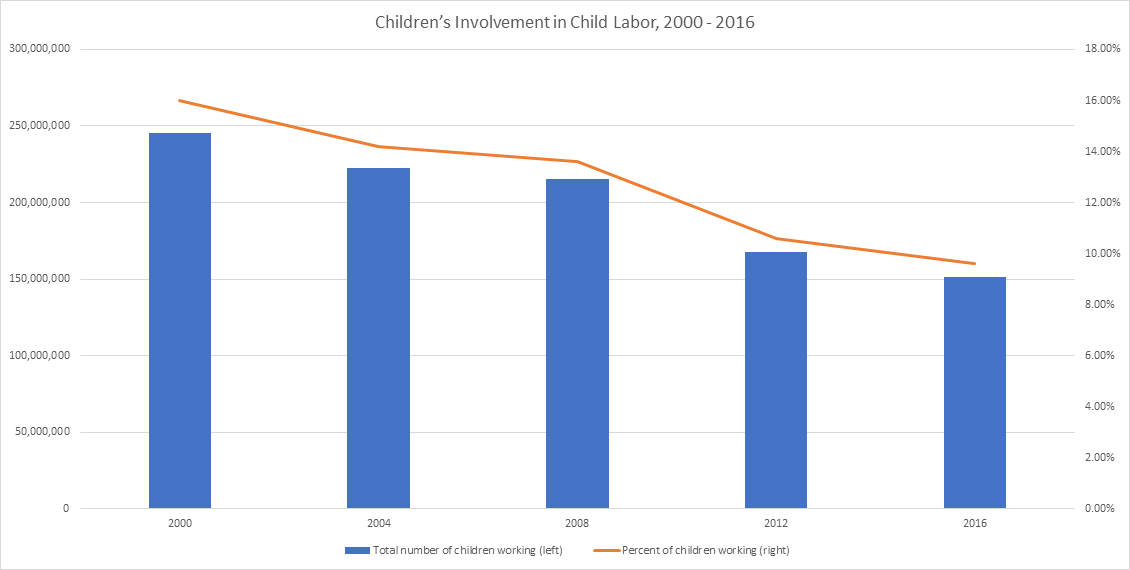

In an article for CapX last week, I discussed Johan Norberg’s new book, Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future. As Norberg notes, over the last two centuries, humanity has made massive improvements in terms of nutrition, sanitation, life expectancy, poverty, violence, literacy, environmental quality, political freedom and child labor.

Today, I want to discuss the role that the Industrial Revolution in general and fossil fuels in particular have played in bringing those improvements about.

Those readers who are familiar with Alex Epstein’s excellent The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels will recognize the gist of my argument: fossil fuels, which drive, among other things, modern agriculture and industrial production, make present-day abundance possible.

Remove cheap energy and most aspects of modern life, from car manufacturing and cheap flights to microwaves and hospital incubators, become a luxury, rather than a mundane, everyday occurrence and expectation.

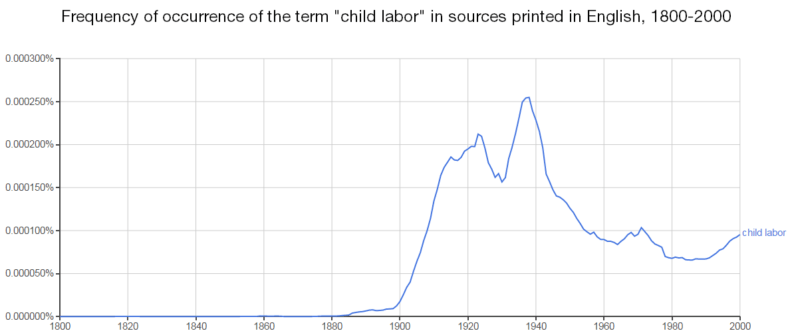

Yet the Industrial Revolution has become tainted (in the popular imagination) with the very problems that it has helped to cure.

Play a word association game with most high school and college students today, and you will observe the negative connotations linking the Industrial Revolution and environmental degradation, exploitation, child labor, poverty, hunger, etc.

If my argument strikes you as anecdotal, consider the following statements:

Writing in The Independent in 2010, David Keys noted, “Huge factory expansion would not have been possible without exploitation of the young … the exploitation of children massively increased […] in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.”

Writing in The Nation in 2015, Greg Grandin observed, “Each generation seems condemned to have to prove the obvious anew: slavery created the modern world, and the modern world’s divisions are the product of slavery.”

And then there is E. P. Thompson’s classic 1963 book, The Making of the English Working Class. According to the author:

“The experience of immiseration came upon them [people in 19th century England] in a hundred different forms; for the field laborer, the loss of his common rights and the vestiges of village democracy; for the artisan, the loss of his craftsman’s status; for the weaver, the loss of livelihood and of independence; for the child, the loss of work and play in the home; for many groups of workers whose real earnings improved, the loss of security, leisure and the deterioration of the urban environment…

Wage cutting [during the Industrial Revolution] had long been sanctioned not only by the employer’s greed but by the widely-diffused theory that poverty was an essential goad to industry.”

This is, by necessity, a tiny sample of massive literature and commentary that ties the Industrial Revolution and, consequently, free trade and capitalism, to human suffering.

I am going to try to convince you of the opposite: that the Industrial Revolution, and the fossil fuels that powered it, contributed to the liberation of humankind.

Homo sapiens is, probably, 200,000 years old. For 99 percent of our existence on this planet, we have derived most of our energy from the labor of people and animals. Only a small fraction of our energy came from water wheels and windmills.

Fire was also a source of energy. But it was extremely dangerous and of limited use. Cooking of food, for example, led to such disasters as the Great Fire of London in 1666. It was also catastrophic for the environment.

One theory of the origins of the Industrial Revolution holds that the English resorted to fossil fuels because they ran out of trees. (Using wood to cook food and keep warm, incidentally, remains the primary source of environmental degradation in Africa.)

Our dependence on energy produced by people and animals helps to explain why slavery was a universal and eternal phenomenon. Defeated peoples on all continents and throughout human history were either killed or put to work as slaves.

There were no internment camps to hold captive populations. Until very recently, prisons were short-term holding cells, where the accused awaited trial, punishment and execution.

More often than not, punishment involved some form of a financial penalty, beating or mutilation, not a lengthy prison sentence at the public expense. The notion of housing and feeding former enemy combatants would strike our calorie-deprived ancestors as utterly insane.

Understandably, if parochially, American and British historians and intellectuals tend to focus on the most recent examples of slavery – that of African slaves in the American south and the sugar islands of the Caribbean.There is nothing wrong with remembering and appreciating the horrors of African slavery, of course, but let us not lose sight of a global perspective.

The very word “slave” probably derives from late Latin “sclavus”, which in turn denotes the Slavic peoples of Central and Eastern Europe who were enslaved by the Turks. Incidentally, the Roman word for a slave was not sclavus but “servus.” Servus, which is where the English word “servant” comes from, remains a popular greeting, akin to “hello”, among the people of Central and Eastern Europe.

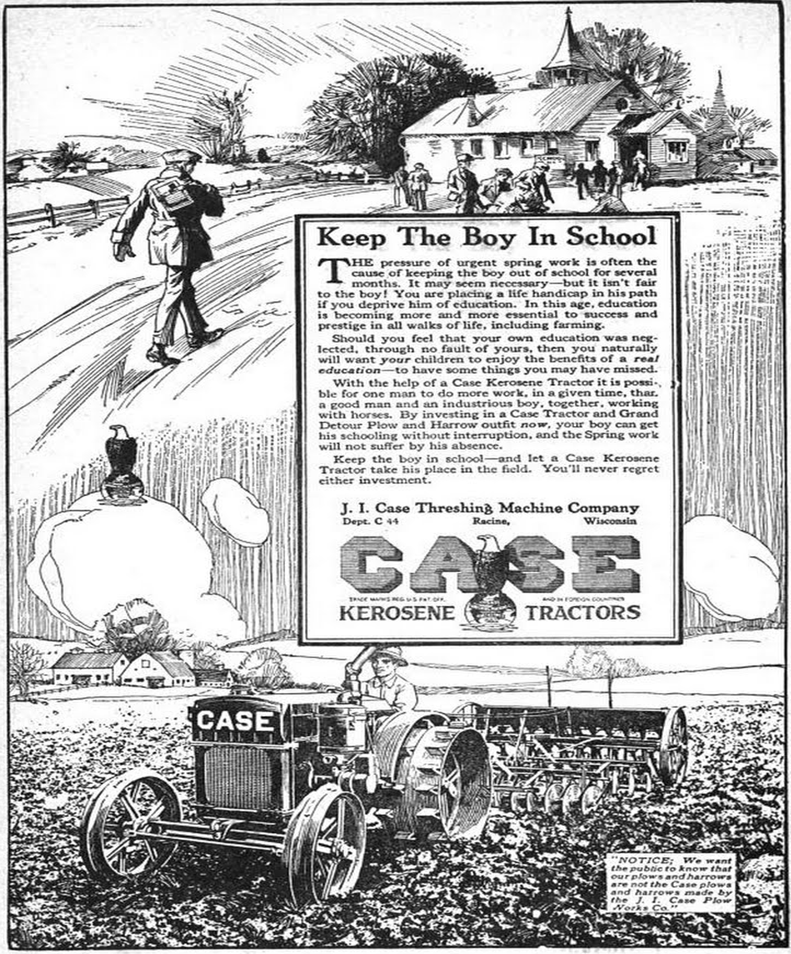

The same applies to child labor. According to the economic historian Eli Heckscher:

“The notion that child labor in either theory or practice was a result of the Industrial Revolution is diametrically opposed to reality. Under mercantilism it was ideal to employ children almost from the age when they could walk, and, for example Colbert [Louis XIV’s Minister of Finance from 1665 to 1683] introduced fines for parents who did not put their six-year-old children to work in one of his particularly cherished industries.”

As Norberg notes:

“In old tapestries and paintings from at least the medieval period, children are portrayed as an integral part of the household economy.… Many worked hard in small work-shops and in home-based industry, and some scholars suggest that this was more intense and exploitative than child labor during industrialization. In the worst cases, children climbed chimneys and worked in mines. Prior to the mid-19th century it was common for working-class children to start working from seven years of age. Here, as elsewhere, the survival of the family demanded that everybody contributed.”

The slaves and the young, in other words, were a source of much-needed energy – and that brings us to hunger and poverty.

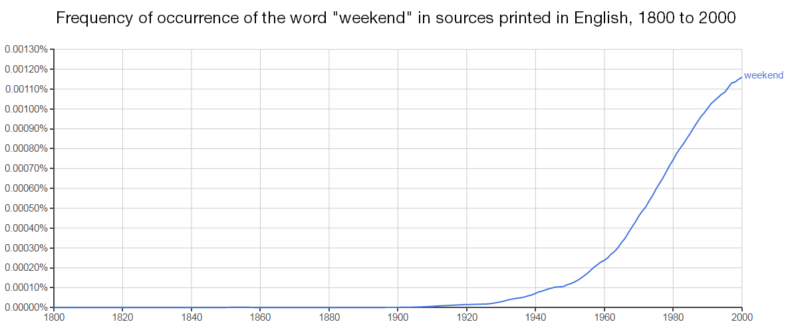

Prior to the Industrial Revolution and burning of coal, gas and oil, most of the calories that people obtained – either directly by planting, growing and harvesting, or indirectly, by manufacturing and trading – they immediately consumed. The exceptions to the rule were the kings, soldiers and priests, who relied on the work of others.

Only very few ordinary people, mostly merchants and money-lenders, broke out of subsistence existence and escaped the vicious cycle of ceaseless manual labor, hunger and poverty.

For the “crime” of escaping from the “natural condition” of poverty, these people were then envied and resented by the bulk of the population.

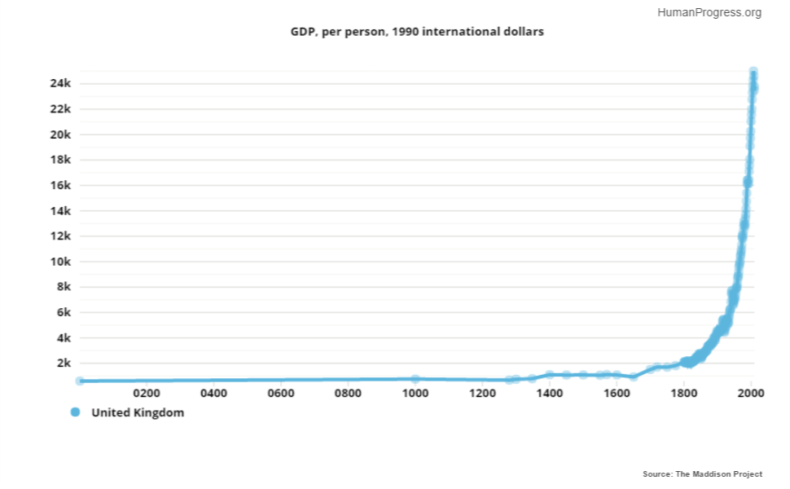

The Industrial Revolution changed all that. Mechanization of agriculture, combined with the use of

guano and, later, synthetic fertilizer, massively improved agricultural productivity.

For the first time, the farm produced more food than the farmers themselves needed to survive. That meant that millions of erstwhile agricultural laborers could move off the farm and into the city.

Factories that sprung up in the urban centers were initially powered by steam that was produced by the burning of coal. Many of the new factories specialized in the production of clothing, which collapsed in price.

This was important. As Carlo Cipolla observed in his 1994 book Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy 1000-1700:

“In preindustrial Europe, the purchase of a garment or the cloth for a garment remained a luxury the common people could only afford a few times in their lives. One of the main preoccupations of hospital administration was to ensure that the clothes of the deceased should not be usurped but should be given to lawful inheritors.During epidemics of plague, the town authorities had to struggle to confiscate the clothes of the dead and to burn them: people waited for others to die so as to take over their clothes – which generally had the effect of spreading the epidemic.”

At first, health and housing in the industrial centers were awful. No European city, after all, was prepared for an influx of millions of people from the countryside.

By the mid-19th century, as T. S. Ashton explains in his 1948 book The Industrial Revolution: 1760–1830, working conditions started to improve and wages started to rise. That, in turn, removed the need for child labor, which rapidly declined.What about the end of slavery?

Here again the Industrial Revolution played an important, though indirect, role. Public sentiments regarding slavery continued to evolve over time. The first millennium, for example, saw slavery abolished in some European countries, including England, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

Unfortunately, the international slave trade continued by and large unimpeded until 1807, when Great Britain abolished the slave trade throughout her global empire and used her naval supremacy to compel other powers, including France and Spain, to do the same.

In any case, British hegemony and naval superiority were connected to the wealth produced and technological innovations spurred by the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution started in Great Britain and it is, therefore, no wonder that it benefited the British Isles first.

Still, the long-term positive effects of the Industrial Revolution were global. The Industrial Revolution did not cause hunger, poverty and child labor. Those were always with us. The Industrial Revolution helped to eliminate them.

This article first appeared in CapX.