Last Friday, the Cato Institute hosted a forum on a new book, Neil Monnery’s Architect of Prosperity: Sir John Cowperthwaite and the Making of Hong Kong. Sir John Cowperthwaite was the financial secretary of Hong Kong between 1961 and 1971, as well its financial under-secretary between 1951 and 1961. As such he has contributed to establishing the policies—small government, low taxes, fiscal probity and free trade—which are credited for turning a poor backwater of the British Empire into one of the richest places on earth.

When I asked Monnery, the British author of the book, to put Hong Kong’s success in context, he noted that in the years following the end of World War II, Hong Kong’s per capita income was one third of that in Britain. By the time of the British transfer of the territory to China in 1997, incomes in the two countries were the same. Today, the average inhabitant of Hong Kong is over 30 percent richer than the average Briton.

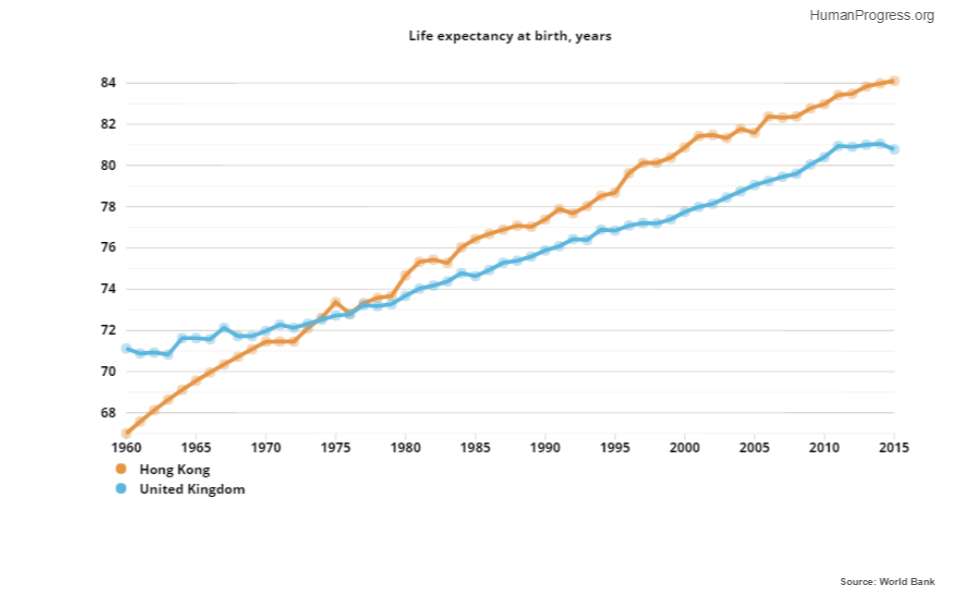

As late as 1960, people in Hong Kong enjoyed lives that were four years shorter than those in Britain. Today, they live four years longer than their British counterparts. Economic growth, we concluded during our discussion, is key not only to rising standards of living, but also to health and life expectancy. Put plainly, the richer the country is, the better the hospitals and higher the quality of care and the environment that it can afford to buy.

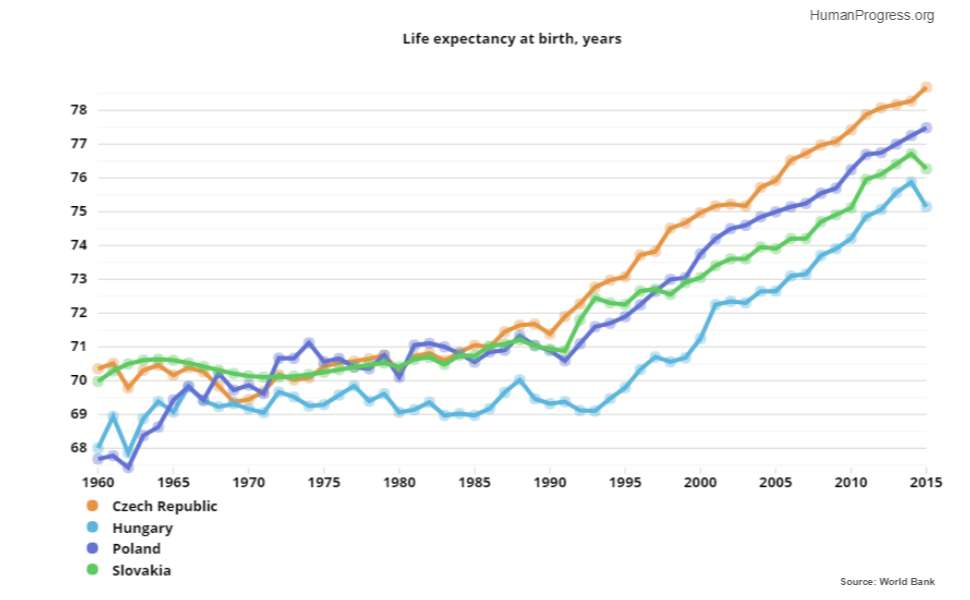

That got me thinking about the region I came from and the changes that Central Europe underwent since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the 28th anniversary of which we will commemorate on November 9. Following the end of the communist period, the region went into an economic recession, as unproductive industries shut down and millions of people lost their jobs. Life expectancy started to decline, which opponents of market reforms saw as proof positive of capitalism’s deleterious consequences for people’s welfare.

Revisiting the life expectancy statistics some three decades later, a different picture emerges. Between 1960, the first year for which World Bank data is available, and 1989 (i.e., a period of 29 years), life expectancy in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia rose by 1.33, 1.46, 3.36 and 1.05 years respectively. Between 1989 and 2015 (i.e., a period of 26 years), it increased by 7.1, 5.68, 6.44 and 5.24 years respectively. The post-communist dip in life expectancy, such as it was, proved to be small and temporary.

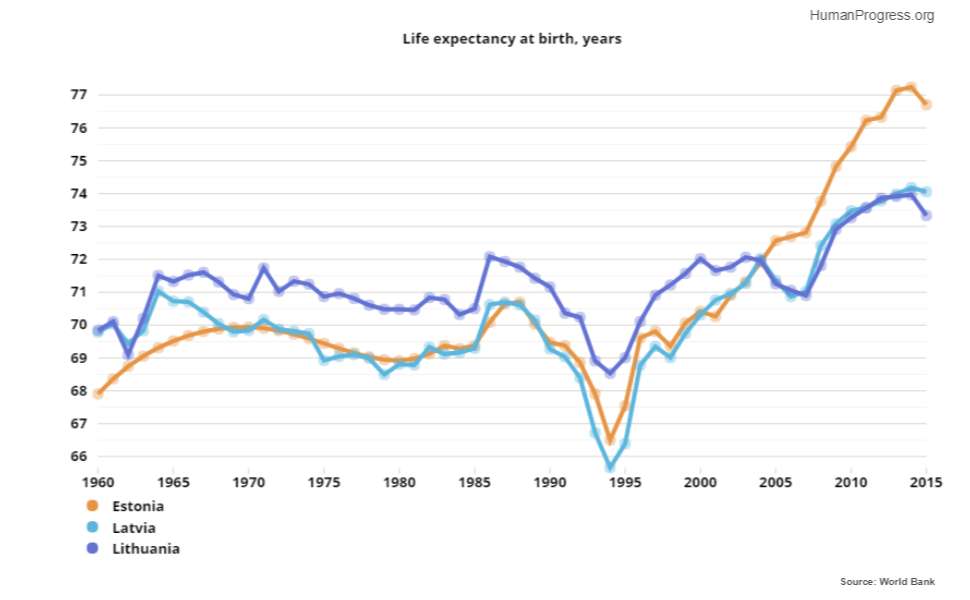

Further afield, post-communist depression was much more pronounced in the Baltic countries, which is, in retrospect, unsurprising. These economies, being parts of the Soviet Union, were much more heavily distorted than their neighbors to the west. In other words, a deeper restructuring was necessary.

Yet, the relationship between economic growth and life expectancy still holds. In the 31 years between 1960 and 1991 (i.e., the year of the dissolution of the U.S.S.R.), life expectancy in Estonia and Lithuania, rose by 1.47 and 0.52 years respectively, while in Latvia it fell by .75 years. Between 1991 and 2015 (i.e., a period of 24 years), life expectancy rose by 7.33 years in Estonia, 2.97 years in Lithuania, and 5.02 years in Latvia.

All in all, a switch from socialism to capitalism appears to be good for the health and longevity of the citizenry.