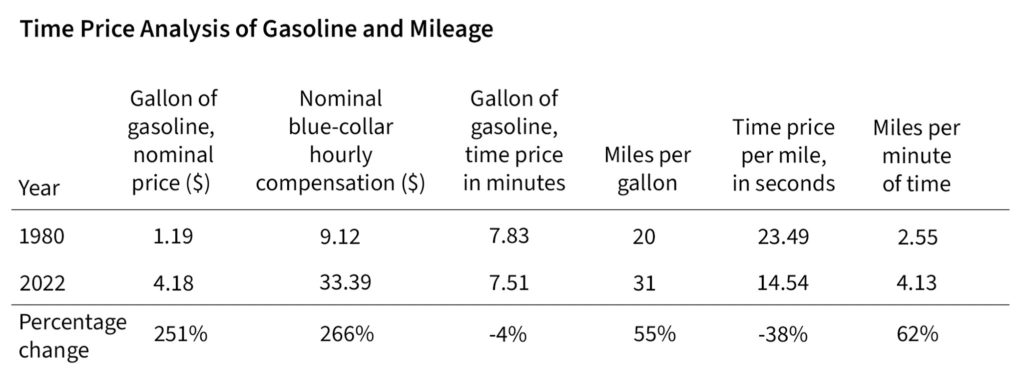

Summary: Although nominal gas prices recently reached historic highs, your time can get you further than ever before. As this article explains, the time price of gasoline has decreased by 4 percent since 1980, and the time price per mile driven has fallen by 38 percent.

The top-selling car in 1980 was the Oldsmobile Cutlass. Gas mileage on this vehicle averaged 20 miles per gallon (17 city/23 highway). By 2022, the Honda CR-V claimed that title. The CR-V reported mileage at 31 miles per gallon (28 city/34 highway). This represents an increase of 55 percent over this 41-year period. Mileage has been increasing at a compound rate of around 1 percent a year.

Back in 1980, gasoline was selling for $1.19 per gallon and blue-collar hourly compensation (wages and benefits) averaged $9.12 per hour. This indicates a time price rate of 7.83 minutes per gallon. Today, gasoline is selling for around $4.18 per gallon and blue-collar hourly compensation is up to $33.39 per hour, indicating a rate of around 7.51 minutes per gallon. While the nominal price of a gallon of gasoline has increased by 251 percent, the time price has actually dropped by 4 percent.

But how much does it cost to travel one mile? That depends on the time price of gasoline and the car’s mileage. In 1980, at 20 miles per gallon, the time price per mile on the Cutlass would have been 23.5 seconds. By 2022, with the CR-V getting 31 miles per gallon, the time price per mile would be around 14.5 seconds. The time price per mile has decreased by 38 percent.

You can look at mileage from the perspective of how many miles you earn per minute of work time. The 1980 Cutlass would have given you 2.55 miles per minute of your time, while the 2022 CR-V gives you 4.13 miles. Gas mileage abundance, from your time perspective, has increased by 62 percent.

There are other differences to consider. NADAguides, a website that values automobiles and other transportation equipment, reports that the price of a new Cutlass in 1980 was $6,735. At $9.12 per hour, it would have taken a blue-collar worker 738 hours to own this new car. Today the CR-V is retailing for around $28,334. At $33.39 per hour, it would take the worker 849 hours to buy one. So, while the time price of the top-selling car has increased by 15 percent, the mileage, safety, reliability, and comfort have all increased by much more.

Yes, nominal gas prices are at historic highs, but it’s not the money that counts, it’s your time. Time prices are the true prices.