This article first appeared in CapX. To read the original, click here.

What is economic growth, and why should it matter to ordinary people? Those questions are hard to answer in a hysterical world where once-dry academic matters are now politicized without fail. Recently, commentators from all sides have taken to dismissing growth as a golden idol of narrow-minded capitalists. Likewise, many people see the pursuit of growth as an alternative, not a complement, to the pursuit of social needs like public health and sustainability.

These narratives are understandable, considering the misinformed and tone-deaf ways in which many public figures have attempted to advocate the importance of growth and economic activity, particularly during the current pandemic. But the narratives themselves could not be more misleading. Economic growth affects the lives of ordinary people in many crucial ways, not just in the West, but importantly in countless developing nations too. In fact, growth is generally the greatest source of improvement in global living standards.

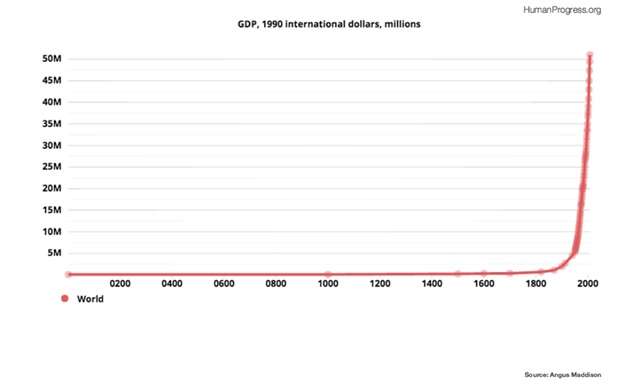

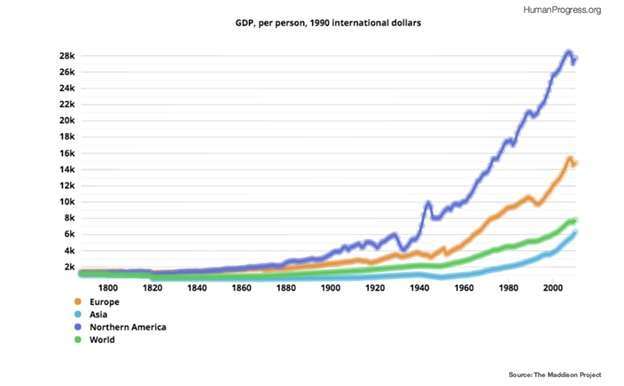

If we visualize the economy as a pie, then growth can be visualized as the pie getting bigger. Most economists measure growth using a metric called Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which defines the pie’s “ingredients” as consumption, investment, government spending and net exports. In developing countries, growth is largely driven by investment, while wealthier countries tend to rely on innovation to continue growing.

These working definitions, while highly simplified, are better than nothing. They are important because they can make it easier to understand how GDP correlates with countless key metrics of living standards.

In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, Real Average GDP per Capita grew by 42% between 1990 and 2018. That growth corresponded to major decreases in extreme poverty, infant mortality and undernourishment.

Growth also increases access to resources that make people safer and healthier. A 2019 paper shows that, while disaster-related fatality rates fell for all global income groups between 1980 and 2016, developing countries in the early stages of growth experienced the greatest improvements. That is because those countries made the greatest relative advances in infrastructure and safety measures—advances facilitated by growth.

Growth is a saving grace for the world’s poorest people, but it also has a major impact on the daily lives of Americans and the rest of the developed world, and that impact is especially important in the age of coronavirus. For example, continuous growth has led to lifesaving breakthroughs in medical technology and research, which has allowed humanity to fight COVID-19 more quickly and effectively than we ever could have in the past. Vaccines for certain ailments took decades to develop as late as the mid-20th century, but it is quite possible that a vaccine for COVID-19 will be widely available just one year after the virus’s initial outbreak.

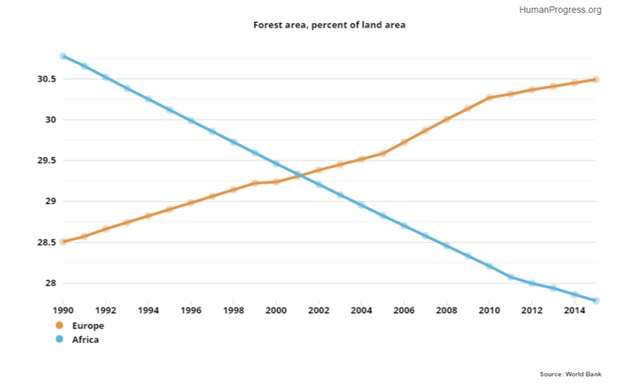

To many supposedly environmentally conscious critics, it seems intuitive that growth is not sustainable. However, sustainability-based criticisms of growth tend to ignore the reality that growth leads to green innovations that help the planet. Labor-augmenting technologies allow us to produce more while conserving resources and protecting the environment. Moreover, wealthier countries are better equipped to develop and adopt green technologies.

MIT scientist Andrew McAfee has documented many of the concrete environmental benefits of growth in his recent book, More From Less. McAfee notes that increases in America’s population and productive activity in recent decades have coincided with significant decreases in air and water pollution, along with gross reductions in the uses of water, fertilizer, minerals and other resources—all because economic growth and market coordination led to improvements in manufacturing and technology. For facilitating this process, which McAfee calls “dematerialization,” growth should be seen as a key to sustainability, not a barrier.

In a broader sense, growth has made our lives more convenient, dynamic and entertaining via developments in consumer technologies and other innovations. Imagine quarantining for five months (and counting) without the internet, PCs or smartphones. Many people would have no way of doing their jobs. Even for those that could, life would be much more difficult, not to mention dull.

Indeed, if one thing could be said to summarize the impact of growth around the world, it would be that growth makes everyone’s life easier. For instance, the amount of labor needed for average workers to purchase countless basic goods and services is at an all-time low and decreasing, largely because supply chains have grown and become more efficient. The result is that ordinary people, especially those in lower income groups with relatively greater reliance on basic goods, are better off.

The story of economic growth is in many ways the story of how cooperation and exchange can defeat poverty and scarcity. The better we understand that, the more likely we will be to support policies which allow resources to flow into areas that need them the most. Broadly speaking, no political idea has been more effective in this regard than free trade.

Knowing the importance of innovation to human well-being should also encourage us to embrace new technology instead of fearing it. We must therefore be wary of overbearing regulations and fiscal policies that prevent ideas from flourishing.

Most importantly, we should not listen to those who claim that economic growth is a pointless, abstract goal that only benefits the rich and leaves ordinary people behind. Growth is a vital driver of progress in modern society and should be taken seriously for the sake of humanity and the planet.