The price of Liberty is eternal vigilance.

Thomas Jefferson

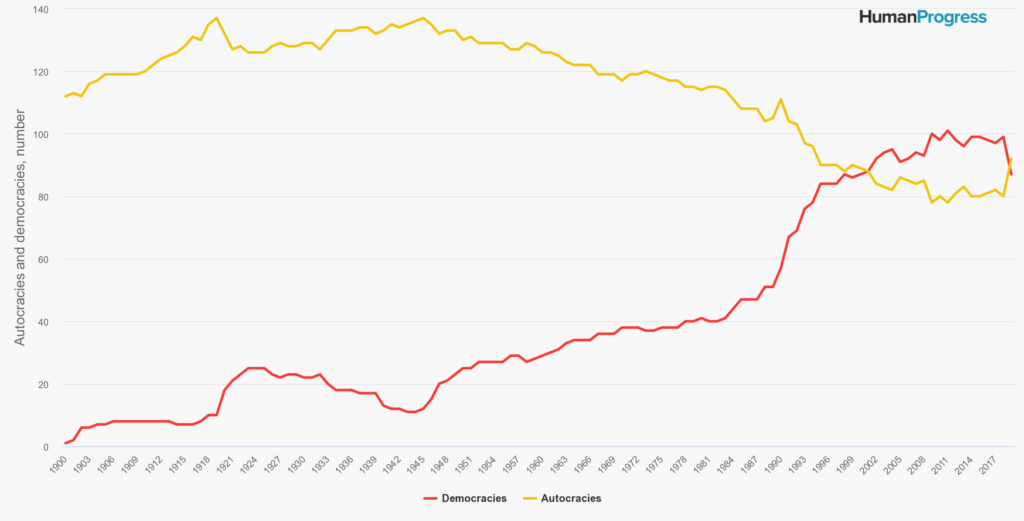

While we are seeing human progress across many well-being indicators, on the dimension of freedom and democracy, the trend is less clear in recent decades. Reports from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute show three major trends regarding the decline of the global levels of democracy.

First, the global level of democracy, as measured by a population-weighted average level of the V-Dem’s Liberal Democracy Indices, has been declining steadily since the 2010s. By 2022, the level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen deteriorated to 1986 levels. In the Asia-Pacific region, the level of democracy fell back to levels last recorded in 1978.

While we can still say that there has been global progress in democracy compared with the early 1970s, when the “third wave of democratization” began, the decline of democracy in the last decade largely wiped out the 35 years of improvement.

Second, the number of countries that moved from democracy toward autocracy (the “autocratizers”) over the last decade is far greater than the number of countries moving from autocracy toward democracy (the “democratizers”). In 2022, there was a record number of 42 autocratizers, containing 43 percent of the world’s population. In comparison, the number of democratizing countries was 14, with only 2 percent of the world’s population. This is a record low number last seen in 1973—50 years ago.

Third, the global balance of power has also been shifting significantly in favor of autocracies. In particular, autocracies accounted for 46 percent of global GDP (in purchasing power parity) in 2022, up from 24 percent in 1992. Trade between democracies was 47 percent of world trade in 2022, down from 74 percent in 1998, with an increasing share of world trade happening with and between autocracies. Democracies’ trade dependency on autocracies grew from 21 percent of world trade in 1999 to 35 percent in 2022. The share of between-autocracies trade tripled from 6 percent of world trade in 1992 to almost 18 percent in 2022.

The Rise of China played a major role in the shifting balance of economic and trade power. In purchasing power parity terms, China’s GDP surpassed the United States around the year 2014, making a closed autocracy the largest economy in the world. As a share of global GDP, China rose from 4.4 percent in 1992 to 18.5 percent in 2022. China also accounts for a significant part of the trade pattern changes, with its share of global trade reaching almost 15 percent and being a major trading partner for many autocracies and democracies.

Political scientists have argued that great powers’ influence on the structure of the international system is important in affecting the trajectories of democracies and authoritarian regimes. The implications of the rise of China for the fate of democracy is still an unfolding story.

Overall, these trends are alarming and worth more attention from people who care about democracy and human progress. The progress of political freedom is fundamental for human progress in other areas. It is, therefore, possible that human progress in general could face decline if the trend of autocratization continues.

While the general trend of human progress in the realm of political freedom still prevails – when we look at it from a time horizon of more than 40 years – we should also recognize that progress in freedom is never guaranteed. Freedom is “fragile” and must be, as President Reagan pointed out, “fought for and defended constantly by each generation.”