Today marks the twenty-seventh installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

Our twenty-seventh Center of Progress is Hong Kong during its rapid free-market transformation in the 1960s. After a lengthy struggle with poverty, war and disease, the city managed to rise to prosperity through classical liberal policies.

Today, the freedom that has been so key to Hong Kong’s success is being stripped away. The Chinese mainland has cracked down on the city’s political and civil liberties, leaving its future uncertain. But as my colleague Marian Tupy has noted, “No matter what lies ahead for Hong Kong, we should admire its rise to prosperity through liberal reforms.”

The area where Hong Kong now stands has been inhabited since Paleolithic times, with some of the earliest residents being the She people. The small fishing village that would later become Hong Kong came under the rule of the Chinese Empire during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC). After the Mongol conquest in the 13th century, Hong Kong saw its first significant population increase as Song dynasty loyalists sought refuge in the obscure coastal outpost.

Hong Kong’s position on the coast allowed its people to make a living by fishing, collecting salt, and hunting for pearls. However, it also left them under the constant threat of bandits and pirates. One particularly notorious pirate was Cheung Po Tsai (1786–1822), said to have commanded a fleet of 600 pirate ships before the government recruited him to become a naval colonel and fight the Portuguese. His purported hideout on an island six miles off the coast of Hong Kong is now a tourist attraction.

China ceded much of Hong Kong to Britain in 1842 through the Treaty of Nanjing that ended the First Opium War. As trade between China and Britain in silk, porcelain, and tea intensified, the port city became a transportation hub and grew quickly. That growth initially led to overcrowding and unsanitary conditions. Thus, it is unsurprising that when the Third Plague Pandemic (1855–1945) took some 12 million lives globally and devasted Asia, it did not spare Hong Kong.

In 1894, the Bubonic Plague arrived in the city and killed over 93 percent of those infected. The plague and resulting exodus caused a major economic downturn, with a thousand Hong Kongers departing daily at the pandemic’s peak. In total, around 85,000 of the city’s 200,000 ethnically Chinese residents left Hong Kong. The Bubonic Plague remained endemic on the island until 1929. Even after the Bubonic Plague departed, Hong Kong remained unhygienic and ravaged by tuberculosis, or the “white plague.”

Besides disease, life in Hong Kong was also complicated by war and instability on the Chinese mainland. In 1898, the Second Opium War (1898) brought Hong Kong’s Kowloon peninsula under British control.

The suffering in Hong Kong was well documented by journalist Martha Gellhorn, who arrived with her husband, the author Ernest Hemingway, in February 1941. Hemingway would later ironically refer to the trip as their honeymoon. Gellhorn wrote, “The streets were full of pavement sleepers at night … The crimes were street vending without a license, and a fine no one could pay. These people were the real Hong Kong and this was the most cruel poverty, worse than any I had seen before.” Yet things were about to get even worse for the city.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), much of the material aid that China received from the Allied Nations arrived through its ports—particularly the British colony of Hong Kong, which brought in roughly 40 percent of outside supplies. In other words, the city was a strategic target. British authorities evacuated European women and children from the city in anticipation of an attack. In December 1941, on the same morning that Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, Japan also attacked Hong Kong, starting with an aerial bombardment. The British chose to blow up many of Hong Kong’s bridges and other key points of infrastructure to slow the Japanese military’s advance, but to no avail.

Following the Battle of Hong Kong, the Japanese occupied the city for three years and eight months (1941–1945). The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology refers to the episode as perhaps “the darkest period of Hong Kong’s history.” The occupying forces executed around 10,000 Hong Kong civilians and infamously tortured, raped, and mutilated many others. The situation prompted many Hong Kongers to flee, and the city’s population rapidly shrunk from 1.6 million to 600,000 people during the occupation. After the Japanese surrendered to American forces in 1945, the British returned to Hong Kong.

That same year, a 30-year-old civil servant from Scotland named Sir John James Cowperthwaite came to the colony to help oversee its economic development as part of the Department of Supplies, Trade, and Industry. He was originally assigned to go to Hong Kong in 1941, but the Japanese occupation forced his reassignment to Sierra Leone. When he finally arrived in Hong Kong, he observed a war-ravaged city in an even worse state of poverty than Gellhorn had described. It was appropriately nicknamed “the barren island.” With the entrepot business stalled, the British considered handing the seemingly hopeless city filled with war refugees back to China.

But Cowperthwaite had some ideas that would help transform Hong Kong from one of the poorest places on the planet to one of the most prosperous.

What was the miraculous intervention that he proposed? Simply allowing Hong Kong’s people to rebuild their shops, engage in exchange, and ultimately save themselves and make their city rich. Cowperthwaite trusted in the capabilities of ordinary people to run their own lives and businesses. He and his fellow administrators provided the city freedom, public security, the rule of law, and a stable currency, and left the rest to the people. To put it simply, he enacted a policy of doing nothing. That isn’t to say he actually did nothing; keeping the other bureaucrats in check kept him plenty busy. He would later claim one of the actions he was most proud of was to prevent collection of statistics that could potentially justify economic intervention.

Cowperthwaite rose steadily through the bureaucracy and eventually became Hong Kong’s Financial Secretary, a post he occupied from 1961 to 1971. During the 1960s, many countries experimented with centralized economic planning and high degrees of public spending financed by heavy taxes and large deficits. The idea that governments should attempt to steer the economy, from industrial planning to intentional inflation, was virtually a global consensus. Cowperthwaite resisted the political pressure to follow suit. From 1964 to 1970, Britain was ruled by a Labour Government that favored heavy-handed economic intervention, but Cowperthwaite ran constant interference to keep his compatriots from meddling with Hong Kong’s market.

As the Communist-controlled Chinese mainland violently purged any remnants of capitalism (among other things) during the reign of terror later called the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), Hong Kong went down a markedly different path.

In 1961, in his first budget speech, Cowperthwaite opined, “In the long run, the aggregate of decisions of individual businessmen, exercising individual judgment in a free economy, even if often mistaken, is less likely to do harm than the centralized decisions of a government, and certainly the harm is likely to be counteracted faster.”

He turned out to be right. Once freed, Hong Kong’s economy became breathtakingly efficient and saw explosive economic growth. The city was among the first in East Asia to fully industrialize and just as rapidly moved to post-industrial prosperity. Hong Kong soon became an international center of finance and commerce, earning its nickname, “Asia’s World City.” Hong Kong’s economic rise dramatically improved the local standard of living. During Cowperthwaite’s tenure as Financial Secretary, Hong Kong’s real wages rose 50 percent, and the number of households in acute poverty fell by two-thirds.

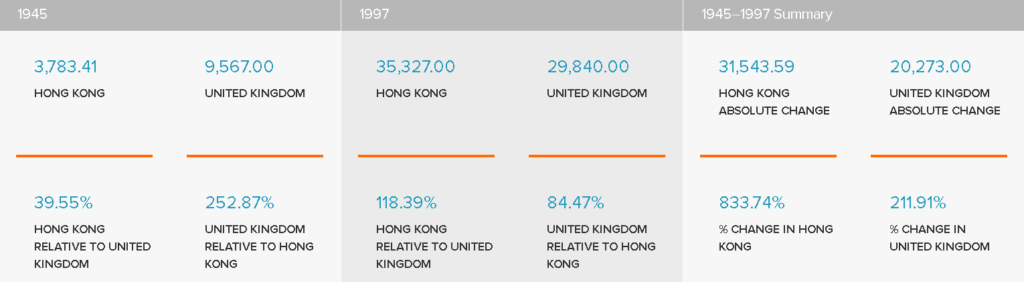

When the Scotsman arrived in Hong Kong in 1945, the average income in Hong Kong was less than 40 percent that of Great Britain. But by the time Hong Kong was returned to China in 1997, its average income was higher than Britain’s.

Cowperthwaite’s successor, Sir Philip Haddon-Cave, named Cowperthwaite’s strategy the “doctrine of positive non-interventionism.” Positive non-interventionism became the official policy of the Hong Kong Government and remained so as recently as the 2010s. For years, the city boasted the world’s freest economy, with bustling financial and trade industries and a human rights record far superior to that of the Chinese mainland.

Then in 2019, Beijing began requiring extradition of fugitives in Hong Kong to the mainland—eroding the independence of Hong Kong’s legal system. In response to the resulting mass protests, the mainland Chinese government implemented a brutal crackdown on Hong Kong’s political and economic independence. In July 2020, a new national security law imposed by the Communist government in Beijing criminalized protests and stripped away several other freedoms previously enjoyed by Hong Kongers. Sweeping changes continue, most recently with an overhaul of Hong Kong’s education system.

Hong Kong was returned to China on the condition that it would remain autonomous until 2047. But the “autonomous territory” is, sadly, no longer truly autonomous.

From a starving city plagued by war and poverty to a shining beacon of prosperity and freedom, Hong Kong’s rise exemplified the potential of limited government, rule of law, economic freedom, and fiscal probity. Sadly, the pillars upon which Hong Kong’s success was built are now crumbling in the tightening fists of the Chinese Communist Party. Whatever the future may hold for the island city, its transformation reflects how much people can achieve when given the freedom to do so. This historic policy lesson merits Hong Kong’s place as our 27th Center of Progress.