In recent years, many US politicians and journalists have warned that the millennials are at the risk of ending up “poorer than their parents.” The evidence certainly suggests that the Great Recession has led to wage stagnation and high unemployment among young Americans, who have soured on the idea of achieving the American Dream.

The just-released Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation’s Annual Report on Generational Attitudes toward Socialism in America, for example, has found that 52 per cent of millennials would prefer to live in a socialist (46 per cent) or a communist (6 per cent) country. Conversely, only 40 per cent want to live in a capitalist one. Mercifully, Americans tend to associate socialism with the high-tax and high-redistribution welfare states of Scandinavia rather than the Marxist dictatorships of the days of yore.

Before they reject American-style capitalism, however, millennials should consider how prosperous ordinary Americans really are.

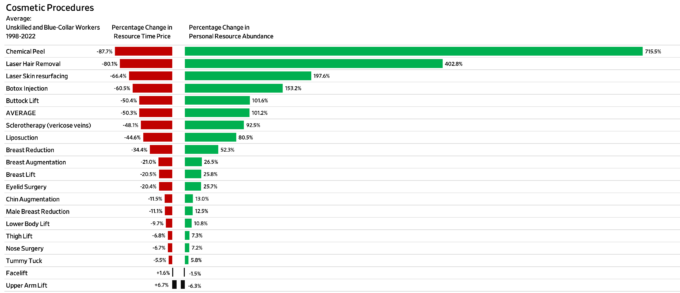

Economic prosperity is often measured in terms of personal income or wealth. Neither of those two measures, however, provides a full picture of people’s material wellbeing, for standards of living can increase due to either income growth or falling prices. People with stagnating incomes, for example, can experience material improvements if prices decline. Even people with falling incomes can be better off – as long as the cost of living decreases at a faster pace than incomes shrink.

As Ball State University economist Steven Horwitz wrote in his 2015 article Inequality, Mobility and Being Poor in America, “If the reason we care about incomes and wealth is because of what they enable people to consume, and thereby acquire goods that add to some broad notion of well-being, then it might also be worthwhile to look at some of the data on consumption to see what it suggests about … the real condition of the poor.”

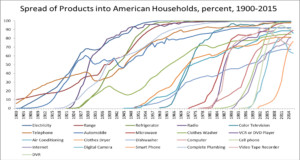

Consider the cost and adoption of home appliances. As late as 1971, only 43.3 per cent of all US households had a colour TV. By 2005, 97.4 per cent of poor American households owned one. Similar stories can be told of washing machines, dishwashers, clothes dryers, refrigerators, freezers, stoves and vacuum cleaners.

As Horwitz noted, “Poor US households are more likely to have basic appliances than the average household of the 1970s, and those appliances are of much higher quality.” Not only do more people across the income spectrum enjoy access to previously unaffordable goods, but the speed of adoption of new products is increasing.

As W Michael Cox and Richard Alm from the Southern Methodist University showed in their 2015 paper Onward and Upward: Bet on Capitalism—It Works, it took about 50 years between the time that the telephone was invented and the time that 50 per cent of US households owned one. In contrast, it took just 12 years from the emerge of the smartphone for 50 per cent of individual Americans to own one.

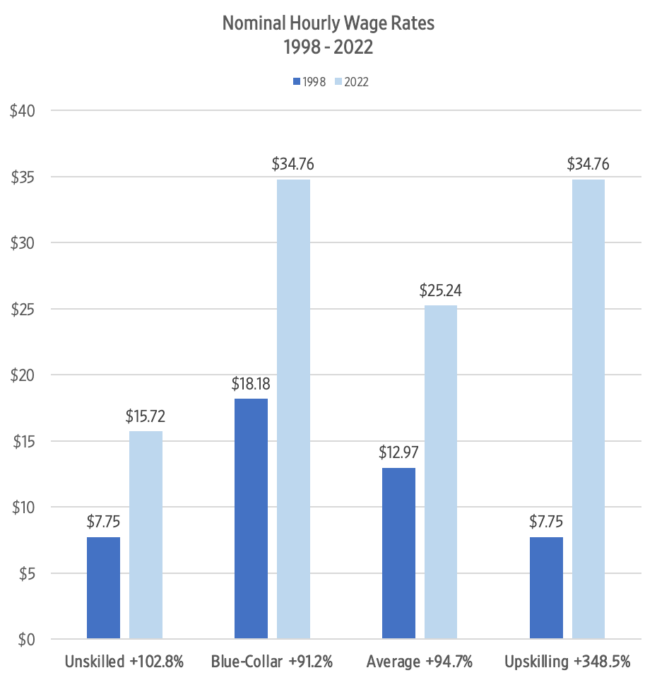

Note that all this material progress took place even though the hourly wages of many American workers stagnated. Between January 1968 and January 2018, the inflation-adjusted average hourly wage in the manufacturing sector rose from $20.43 to $21.27. Manufacturing accounts for 19 percent of all US employment and wage stagnation among factory workers may be seen as analogous to the flat-lining incomes among millennials.

Source: W Michael Cox and Richard Alm, Onward and Upward: Bet on Capitalism—It Works

Bearing the above wage numbers in mind, how come most Americans can now enjoy goods that were previously owned only by the rich?

First, it is important to note that hourly wages do not reflect the massive expansion in non-wage benefits, which rose from 19 per cent of wages in 1951 to 44 per cent in 2015. Today non-wage benefits include relocation assistance, medical and prescription coverage, vision and dental coverage, health and dependent care, flexible spending accounts, retirement benefit plans, group-term life and long-term care insurance plans, legal and adoption assistance plans, child care and transportation benefits, vacation and sick paid time-off, and employee discount programs from a variety of vendors, etc.

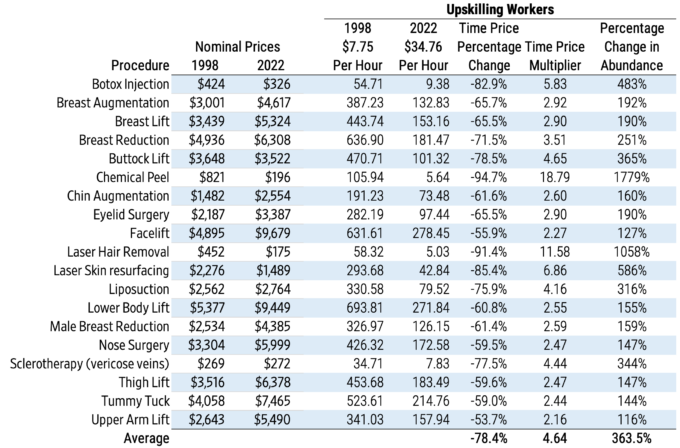

Also, many commonly owned goods have declined in price. In 1968, for example, a 23” Admiral colour TV cost $2,544 or 125 hours of labour in the manufacturing sector. In 2018, a 24” Sceptre HD LED TV cost $99.99 or 4.7 hours of labour in the same sector (all prices are in 2018 US dollars). That’s a reduction of 96 per cent in terms of human effort.

The upshot is that growth in nominal wages, or lack thereof, does not reflect the real changes in the standard of living experienced by vast majority of Americans. That’s something to keep in mind when young Americans contemplate the choice between capitalism and socialism.

This first appeared in CapX.