Summary: Free trade is often accused of being unfair and corrosive to democratic institutions, concentrating power in the hands of elites while leaving ordinary people behind. The evidence suggests the opposite. Participation in markets cultivates norms of fairness, impartiality, and trust that strengthen democratic institutions and expand individual rights.

In earlier essays, I argued that trade makes us more prosperous, more trusting, and less corrupt. But isn’t trade unfair? Doesn’t the constant churn of global competition take power out of the hands of ordinary people and place it in the hands of wealthy individuals and corporations? Is democracy dying a slow death from the disease of globalization? As I show in this essay, the answer to each of these questions is an emphatic no. Trade, it turns out, strengthens democratic institutions and encourages more impartial treatment of one another. Overall, the complexity of the globalized economy has made us a much fairer bunch.

The French philosopher Montesquieu wrote, “The spirit of commerce produces in men a certain feeling for exact justice.” As Middlebury political scientist Keegan Callanan notes, Montesquieu believed that everyday trade trains us in habits of fair dealing. Over time, these small, routine acts of fairness cultivate a broader sense of exact justice that extends far beyond the marketplace. And researchers have tried to test this philosophical hunch.

Take the Ultimatum Game as an example. In this experiment, two participants are provided a specific sum of money. One participant is granted the power to divide the sum between the two. If the other player accepts the division—whether it is 50:50 or 99:1—both players keep their share. If the receiver rejects the offer, both go home empty-handed. Harvard anthropologist Joseph Henrich has found that proposers from industrial societies (e.g., United States, Indonesia, Japan, and Israel) tend to make offers between 44 and 48 percent, while the Machiguenga of the Peruvian Amazon offer only 26 percent.

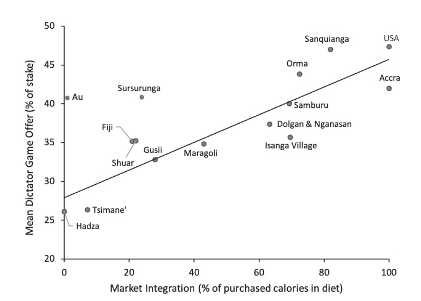

Experiments by Henrich and fellow researchers involving 15 small-scale agrarian societies—consisting of hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, nomadic herders, and sedentary farmers—have also shown that groups more heavily immersed in trade and market exchange with outsiders are less likely to make inequitable offers. Later experiments confirmed “that fairness (making more equal offers) in transactions with anonymous partners is robustly correlated with increasing market integration.”

Within the Ultimatum Game, however, there is still a risk for the proposer: the possibility of going home with nothing if the offer is too small. A proposer might therefore make a more generous offer out of self-interest simply as a strategy to avoid missing out on free money. To explore how deeply rooted this sense of fairness is, Henrich and his colleagues added the Dictator Game to their experiments. In this economic game, the receiver has no opportunity to reject the offer: they get whatever they are given. Yet even under these new rules, Henrich reported that

people living in more market-integrated communities again made higher offers (closer to 50 percent of the stake). People with little or no market integration offered only about a quarter of the stake. Going from a fully subsistence-oriented population with no market integration…to a fully market-integrated community increases offers by 10 to 20 percentile points [see Figure 1].

Even when fairness and generosity have no strategic payoff, market integration predicts more equal treatment.

Figure 1. Dictator Game offers and market integration

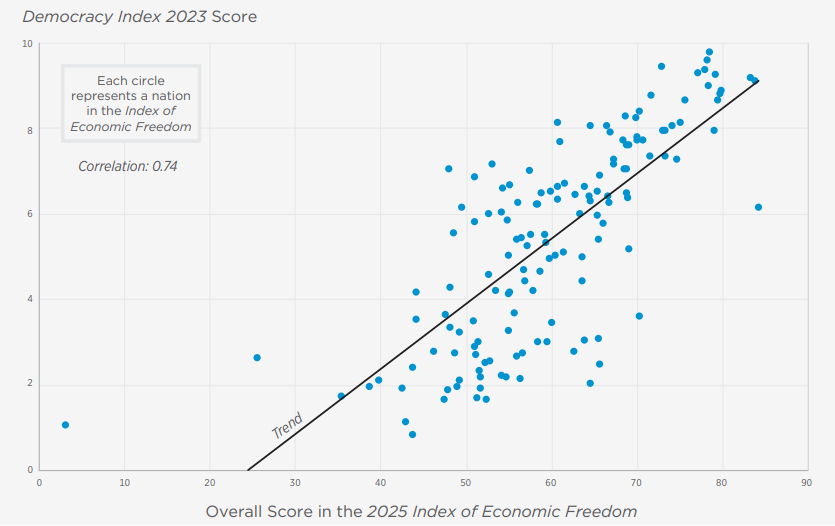

As Montesquieu observed, the habits of fairness developed through everyday trade can extend well beyond the marketplace. Over time, they spill into our civic and political institutions. Democratic governments, in particular, seek to concretize fairness through their procedures and protections. This may help explain why the 2025 Index of Economic Freedom report finds a positive relationship between economic freedom and democratic governance (see Figure 2). Economic freedom, it argues, is “an important stepping stone on the road to democracy.”

Figure 2. Economic freedom and democratic governance

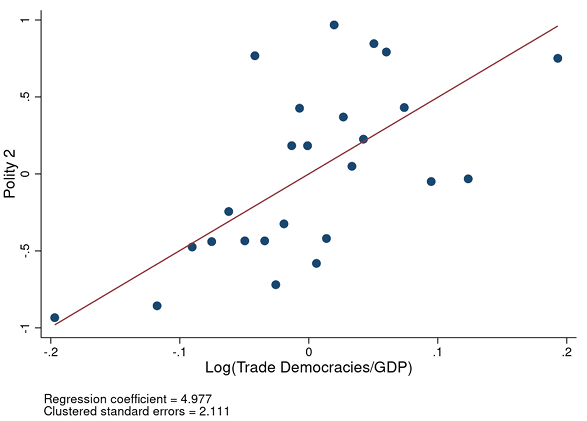

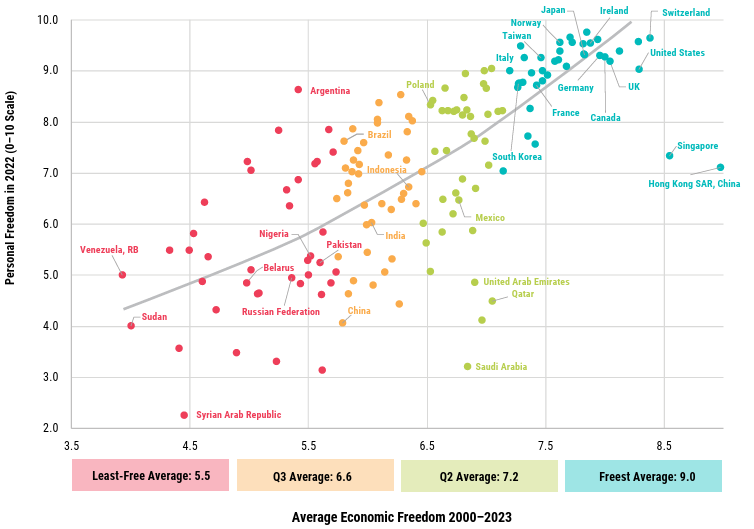

Research has consistently shown trade and market exchange to be champions of democracy. Economists Marco Tabellini and Giacomo Magistretti found that economic integration with democratic countries significantly boosts a country’s democracy scores (see Figure 3). Trade not only transmits goods and services across borders, but also democratic values and institutions. Studies by University of Maribor sociologist Tibor Rutar have also found a positive relationship between trade openness and democracy. Economic freedom has been shown to improve the durability of democratic institutions, while democratic backsliding is often preceded by restrictions on the economy. Political and civil liberties struggle to survive under a heavy-handed state, yet flourish with the expansion of economic freedom (see Figure 4). All in all, democracy and global capitalism appear to be two peas in a pod. As AEI’s Michael Strain explains:

It is no surprise that the rise of populism and economic nationalism has coincided with growing skepticism toward liberal democracy and growing comfort with political violence. The erosion of economic liberalism – free people, free markets, limited government, openness, global commerce – reflects a loss of respect for the choices people make in the marketplace. If we devalue choices made in markets, why wouldn’t we devalue choices made at the ballot box?

Figure 3. Trade with democracies and democratization

Note: The y-axis (Polity 2) shows democracy levels. The x-axis (Log) measures trade with democratic countries (relative to GDP).

Figure 4. Economic freedom and personal freedom

Consider a specific case of unfairness: gender inequality. Generally, fairness is about impartial treatment between various groups. Gender inequality, however, is about impartiality within a group. In Sex and World Peace, Texas A&M’s Valerie Hudson and her colleagues argue that women are often treated as “the boundaries of their nations” because “women physically and culturally reproduce their group.” Far from being outsiders that are merely tolerated, women are seen as the creators and perpetuators of the group itself. “Indeed,” Hudson and her coauthors explain, “this is one of the reasons why the symbol of a nation is often personified as a woman, in order to elicit these deep feelings of protection. A woman becomes a ‘protectee’ of the men of the group, especially those in her own family.”

Unfortunately, the desire to protect women often translates into controlling them. In order to preserve the supposed cultural integrity of the in-group, women’s freedom is restricted. Their behavior becomes closely bound to the honor of their family and community—especially the men of both.

Greater exposure to the global economy, however, weakens this unfair patriarchal hold. For example, political scientists David Richards and Ronald Gelleny explored the effects of economic globalization—measured by foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, trade openness, and IMF and World Bank structural adjustment policies—on what they termed “women’s status” or women’s ability to fully exercise specific rights found in the corpus of international human rights law. Overall, they found that “sixty-seven percent of the statistically significant coefficients indicated an association with improved women’s status.” Similar measures—along with additional indicators such as the number of McDonald’s restaurants and IKEA stores per capita—are associated with improvements in women’s decision-making power within households, freedom in movement and dress, safety from physical violence, ownership rights, and declines in son preference and the number of “missing women.”

Supporting these findings, political scientists Eric Neumayer and Indra de Soysa have shown that increased trade openness reduces forced labor among women and increases their economic rights, including equal pay for equal work, equality in hiring and promotion practices, and the right to gainful employment without the permission of a husband or male relative. Other studies reach similar conclusions. Analyzing global data from 1981 to 2007, Neumayer and de Soysa also found that increased trade openness improves both economic and social rights, including the right to initiate divorce, the right to an education, and freedom from forced sterilization and female genital mutilation.

A study published in the journal International Organization examined four measures of women’s equality: (1) life expectancy at birth, (2) female illiteracy rates among those over age 15, (3) women’s share of the workforce, and (4) women’s share of seats in parliament. The study found that international trade and investment led to improvements in women’s health, literacy, and economic and political participation. The evidence makes clear that economic freedom matters for the well-being of women everywhere (see Figure 5).

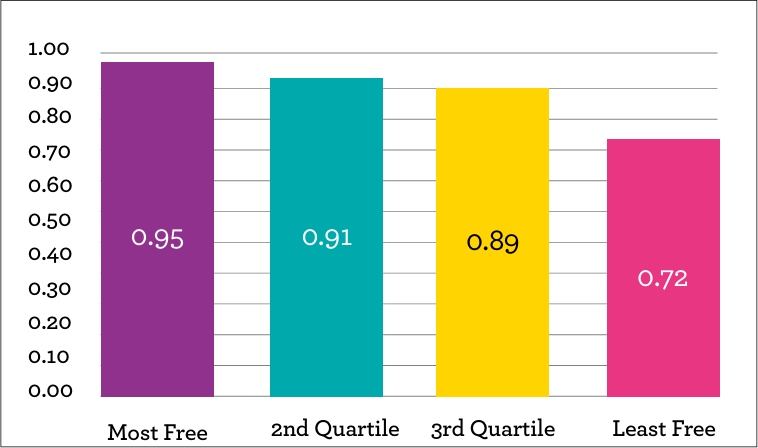

Figure 5. Economic freedom and gender equality

Note: Countries are divided into four quartiles based on their Economic Freedom of the World Index (EFW) scores, from most to least economically free. The EFW measures the size of government, rule of law and property rights, currency stability, trade openness, and regulation. The bars show the average Gender Disparity Index (GDI) score for each quartile. The GDI measures women’s freedom of movement, property rights, freedom to work, and legal status. A higher GDI score indicates greater gender equality.

Unfairness is one of the most common criticisms leveled against commercial society, often accompanied by claims that it undermines democracy and fosters partiality. The evidence presented here suggests the opposite. Engaging in trade and market exchange teaches us to treat others more generously and impartially. The natural outcome of these values is the institutional protection of certain rights. Fair treatment for all becomes the name of the game. We begin to trust one another’s choices and to believe in our shared ability to build society together.