Summary: Many people assume that markets breed dishonesty, but the opposite is true. Commerce depends on trust. Repeated exchange and reputation make honesty not just virtuous, but profitable. When trade is open and competition thrives, deceit is punished and integrity is rewarded. By contrast, heavy regulation invites corruption and favoritism. A truly commercial society, grounded in voluntary exchange and mutual accountability, is also a more honest and trustworthy one.

In my previous essays, I argued that a trade society is both a prosperous and trust-based society. Trust and trustworthiness in society revolve around norms of honesty. Dishonesty breeds distrust and frays the threads of our social fabric. Some may worry that dishonesty is the lifeblood of a commercial society: a system that runs on lies, with an every-man-for-himself attitude and shady opportunists around every corner. In fact, greater honesty is best achieved through reputational pressures and the mutual accountability that is fostered by frequent exchange; frequent exchange is enabled by the removal of corrupting restrictions.

In his Lectures on Jurisprudence, the Scottish economist Adam Smith described the commercial society in the following terms:

Whenever commerce is introduced into any country, probity and punctuality always accompany it . . . Of all the nations in Europe … the most commercial, are the most faithfull to their word … A dealer is afraid of losing his character, and is scrupulous in observing every engagement … When people seldom deal with one another, we find that they are somewhat disposed to cheat … When the greater part of people are merchants they always bring probity and punctuality into fashion, and these therefore are the principal virtues of a commercial nation.

In Smith’s view, fear of reputational damage and unemployment prevents fraud and dishonesty. He believed that success within a commercial society stems from “prudent, just, firm, and temperate conduct” and “almost always depends upon the favour and good opinion of … neighbours and equals; and without a tolerably regular conduct these can very seldom be obtained. The good old proverb, therefore, that honesty is the best policy, holds, in such situations, almost always perfectly true.” For Smith, the market in many ways makes us accountable to each other: repeated dealings and fear of reputational damage incentivize honest behavior. And plenty of empirical evidence supports his outlook.

Laboratory experiments demonstrate that trade teaches participants whom to trust and whom not to. Dishonest behavior is punished in the marketplace, providing an incentive for participants to be honest in their dealings. For example, one study found that adding market competition to the experiment reduced sellers’ over-diagnosis of high-quality treatment (when lower-quality would suffice) and increased buyer trust. Another experiment found that introducing market competition into one-off exchanges boosted trust and efficiency to match that of trading networks built on repeated interactions. Adding market competition and private reputation information in one experiment tripled trust and trustworthiness while increasing efficiency tenfold. By practicing honesty to protect their reputations, trade participants eventually internalize honesty as a habit.

Conversely, trade restrictions lead to greater dishonesty. For example, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) measures the perceived levels of public sector corruption across numerous countries using multiple surveys of business people and country experts (Figure 1). Various studies that rely on the CPICPI have shown that a greater amount of international trade and foreign direct investment and low levels of state control of the economy curtail corruption. High levels of regulation—including regulation on trade—tend to be a strong predictor of corruption. Even seemingly small adjustments to trade procedures can make a difference. For example, the World Bank’s 2020 Doing Business report found that “economies that have adopted electronic means of compliance with regulatory requirements . . . experience a lower incidence of bribery.” That includes digital trade reforms such as electronic single-window systems, e-payments, paperless clearance, online certificate issuance, and more.

Figure 1. Corruption Perceptions Index scale

More recently, a 2023 study looked at firm-level data across 138 countries and confirmed that the imposition of more red tape in public services—such as import licenses—is associated with a greater tendency to pay bribes, particularly in nondemocratic countries. Similarly, a recent study found that India’s trade liberalization since the early 1990s, especially tariff reductions, significantly reduced the economic advantages of politically connected firms by decreasing their reliance on political favoritism. It appears that the friendlier a nation’s economy is to trade, the less corrupt it tends to be. Economic restrictions and regulations allow corruption to grow, instead of the economy. By reducing barriers, more trade is unleashed, which in turn promotes the “probity and punctuality” that Smith described.

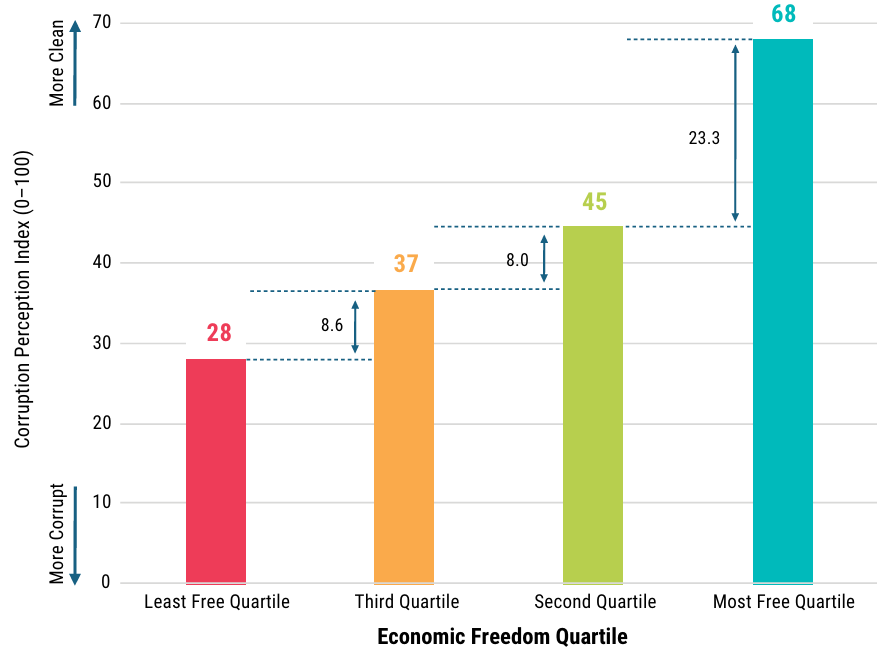

When the level of economic freedom within countries is compared to their level of corruption, economically-free countries come out looking relatively clean. And the scores of the freest countries are more than twice as high as those of the least free countries (Figure 2). That’s because various aspects of economic freedom—including trade openness—are associated with less corruption. Freer trade makes reputation king, mitigating corrupt incentives and embedding honest norms throughout society.

Figure 2. Economic freedom and corruption

As a case in point, East Germany suffered under severe trade restrictions prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall. After testing randomly selected German citizens on their willingness to cheat at a die-rolling game, researchers found that those who had East German (communist) roots were significantly more likely to cheat compared to those with West German (capitalist) roots. It was also shown that the longer the person had exposure to communism and its trade barriers (i.e., those who were at least 20 years old when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 compared to those who were only 10 years old), the greater their likelihood to cheat.

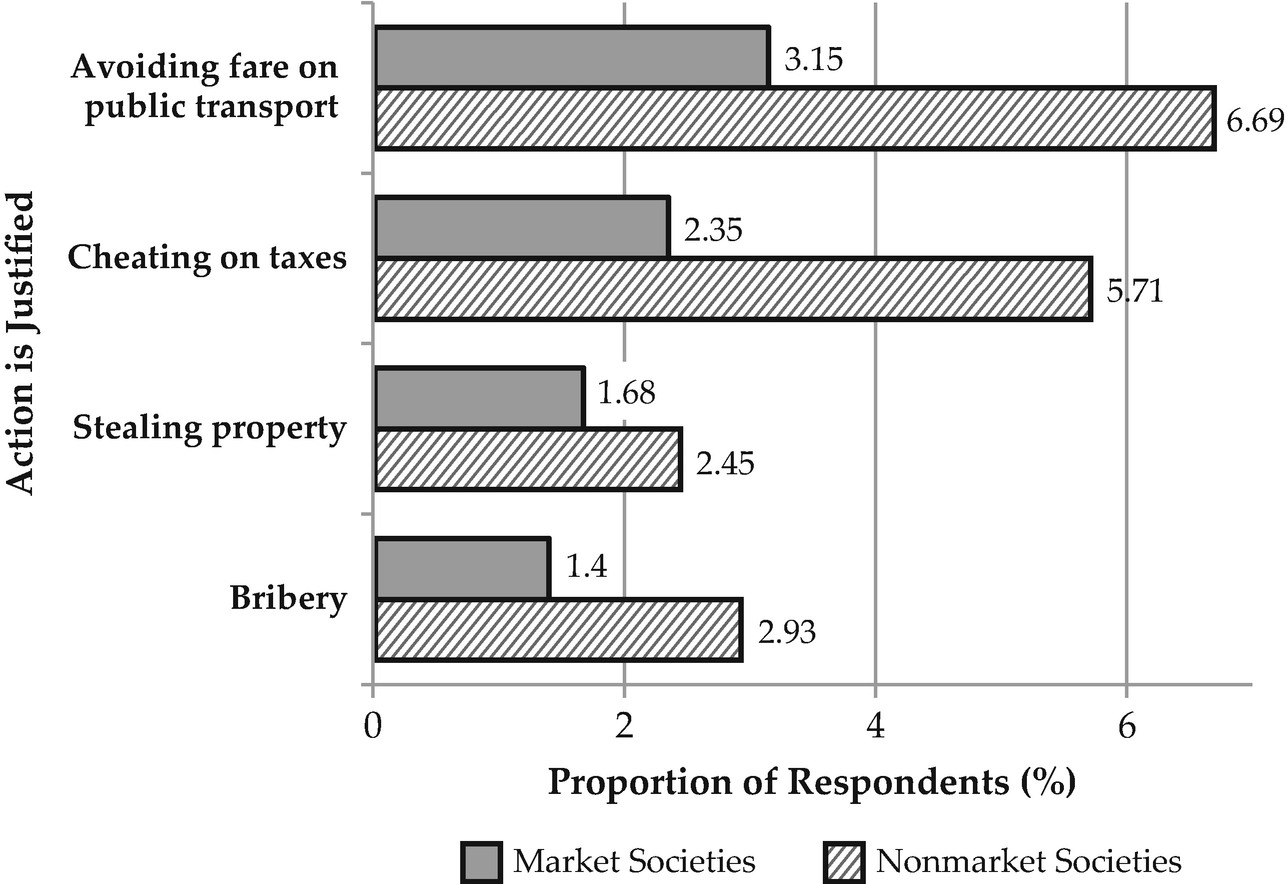

These findings are supported by the work of the Mercatus Center’s Virgil Storr and Ginny Choi, who discovered a significant difference in attitudes between members of nonmarket and market societies: More than double the number of nonmarket residents versus market residents believe that avoiding fares on public transport, cheating on taxes, and bribery are justifiable. Those from nonmarket societies are also more accepting of theft compared to those from market societies (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Market versus nonmarket societies on dishonest behavior

Follow-up studies by other researchers have drawn similar conclusions about market societies and honest behavior. For example, a 2023 study surveyed residents in both market and nonmarket societies on their attitudes toward claiming government benefits to which they are not entitled, avoiding fares on public transport, and cheating on taxes. After controlling for a number of variables, they found that those with greater exposure to markets were less likely to justify these dishonest actions. What’s more, individuals who preferred markets (“market thinking”) were also less likely to justify dishonesty. The researchers concluded that there is “a universal association between markets and morality” and “a robust association between an increase in market exposure and an increase in civic morality.”

Even within communist countries, research shows that the more trade-oriented areas tend to be the least corrupt. A study in China Economic Review employed the National Economic Research Institute (NERI) Index of Marketization, which measures five major fields of Chinese marketization with 23 indicators. Examining different provinces in China, the authors’ analysis found that deregulation and trade reduce corruption: a 1 percent increase in the marketization index leads to a 2.72 percent reduction in corruption. Regions that increased trade openness by 1 percent experienced a 0.35 percent reduction in corruption.

Overall, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that open economies stifle the spread of corruption and reinforce honest habits through reputation-building exchange. The removal of trade barriers allows for more commerce to take place and, consequently, more reputations to be a stake—a powerful incentive to keep honorable reputations intact. The most enduring way to achieve this is through genuinely honest conduct. A commercial society is, at its core, a society of integrity: it limits the opportunities for corruption and encourages honest behavior in the process. The norms of commerce—Smith’s “probity and punctuality”—settle in like a kind of glue, helping to bind society together.