Summary: When President Nixon imposed wage and price controls in 1971, it created chaos. Gas shortages, rationing, and angry customers became daily realities, teaching one young gas station attendant how disastrous top-down economic planning can be. A decade later, when markets were finally freed, supply returned and abundance followed. The lesson endures: politicians create scarcity, but entrepreneurs and free markets create plenty.

Shortly after I turned 15, President Richard M. Nixon managed to make my life miserable. On Sunday August 15, 1971, against the advice of his economic counselors, and in total repudiation of his party’s campaign platform, he announced on national TV that he was suspending the gold standard, imposing a 10 percent tariff surcharge, and imposing wage and price controls.

At the time, I didn’t know a thing about macroeconomics. What I did know was how to make customers happy at my dad’s gas station: Fill their tanks fast, wash their windows, and send them off with a smile.

Nixon’s decision not only shook the foundations of global finance—it trickled all the way down to a teenager pumping gas on Main Street, teaching me firsthand how government policy can reach into everyday life. Nixon’s policies caused a decade of artificial shortages and almost destroyed my father’s business. As Robert Bleiberg, editor of Barron’s, noted at the time, “Price controls, as their advocates have claimed all along, do work like magic. They can make things disappear in the twinkling of an eye.” For me, Nixon’s policies meant no more happy customers, which translated to no more tips.

Like many gas station owners at the time, my dad decided to attempt rationing his limited allotment of fuel by restricting sales to only five gallons per customer. After waiting in line for sometimes more than an hour, most customers were furious to be told that they could only buy five gallons of gas. They took their anger out on their lowly attendant, not on the perpetrator of the calamity living in the White House.

The president, along with the politicians and corporate leaders who cheered for price controls, never had to face the fury of my customers. They could make sweeping decisions from behind their podiums and boardroom tables without ever paying the price for being wrong. As Thomas Sowell once put it, “It is hard to imagine a more stupid or more dangerous way of making decisions than by putting those decisions in the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong.”

Price controls tied the hands of domestic producers while leaving foreign suppliers, such as OPEC, untouched. The result was the opposite of what policymakers had intended. Instead of fueling independence, the policies throttled domestic supply and handed foreign oil giants the keys to America’s energy future.

In 1981, just eight days after taking office, President Ronald Reagan swept away the federal price and allocation controls on domestic oil and refined products. Overnight, my decade of gas-line misery came to an end. Prices did rise—but for the first time in years, people could fill their tanks without rationing, limits, or fear of empty pumps. I learned a key lesson: Politicians create scarcities, entrepreneurs create abundances.

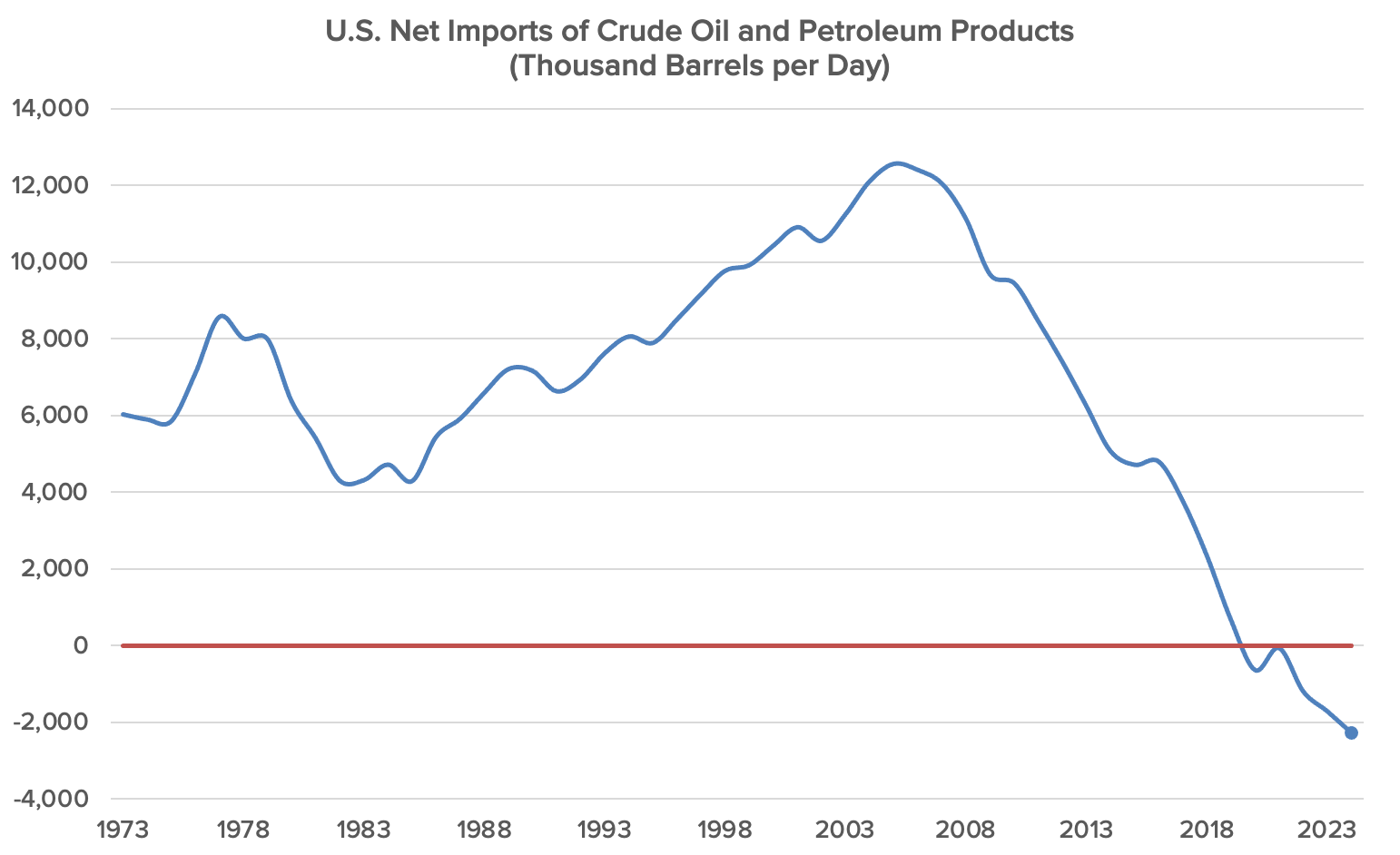

When oil prices surged in the early 2000s, entrepreneurs and markets responded with a wave of innovation. Breakthroughs such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing unlocked vast new oil reserves, unleashing a surge of supply. America’s unique system of private ownership of subsurface mineral rights—rather than government control—supercharged this revolution by giving landowners a direct stake in production. The results were astonishing: The United States, whose oil industry was once thought to be in irreversible decline, has become a net exporter of petroleum products.

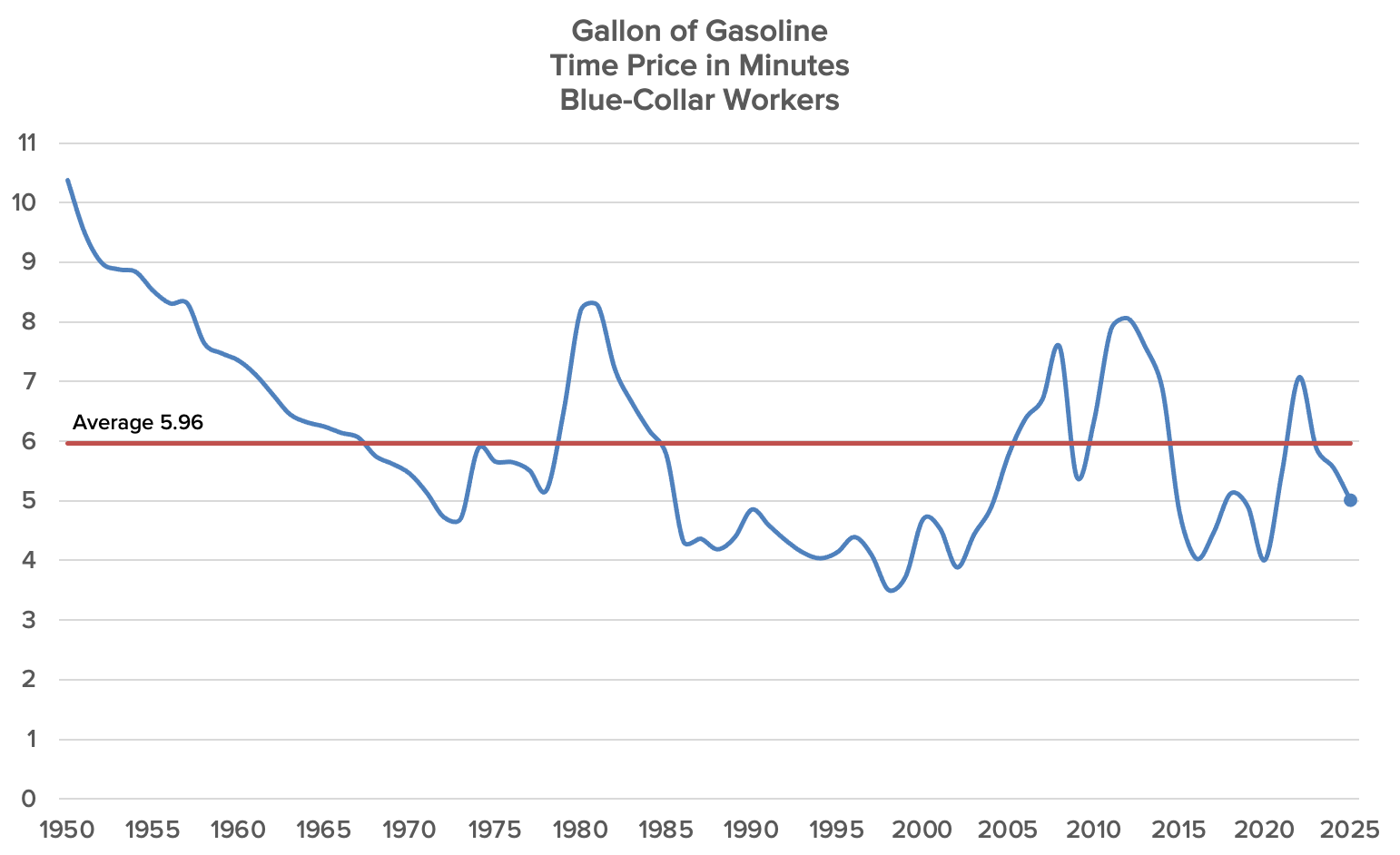

Since 1950 the average time price for a gallon of gasoline has been around six minutes for blue-collar workers. We’re actually around five minutes today. The United States has some of the lowest gasoline time prices on the planet.

Yes, we’ve had periods where the price has spiked, typically due to political turmoil, but time and again, innovation and markets have responded by creating greater abundance. Julian Simon predicted such would be the case, as long as politicians and bureaucrats don’t impose “solutions” that have counter-productive consequences.

Nixon resigned on August 8, 1974, to avoid impeachment for his crime of covering up the Watergate break-in. But to me, his darker crime wasn’t in a hotel—it was in every gas station in America. His Soviet-style controls left behind a nation of frustrated, unhappy customers and pump attendants who bore the real cost of his misguided policies.

Find more of Gale’s work at his Substack, Gale Winds.