British economist John Maynard Keynes once said that “[p}ractical men who believe themselves quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” It’s unclear whether Chinese tech billionaire Jack Ma is a Keynes discipline, or considers himself immune to economists’ musings. But in forecasting that technology and automation might deliver a 12-hour working week, Ma certainly echoes Keynesian thinking about economic progress.

Sharing a stage with U.S. entrepreneur Elon Musk in Shanghai, Alibaba founder Ma this week predicted that artificial intelligence and automation will deliver unheard of gains to productivity. Offering an upbeat story of its effects, he suggested that producing more with fewer workers will reduce the desirable working time to just “three days a week, four hours a day.” Instead, we will be able to spend extra time enjoying “being human beings” and going to “karaoke in the evening.”

In a 1930 essay entitled “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” Keynes made a similar prediction. Within a century, he believed we’d be four to eight times as rich. Such would be the technological advances in production driving more output with less labor input, our economic needs could be fulfilled by just working “three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week.” Even working that long would be reflective of our natural human desire to stay occupied, rather than out of necessity. Keynes even mused that people would have more time to sing too!

As we contemplate the long hours we’ll spend at our desks this next week, it’s easy, in retrospect, to dismiss Keynes’ musing as a flight of fancy. But in fact, a lot of what he wrote was prescient. What he got wrong should make us think skeptically about Ma’s musings of what it means to be human.

Keynes’ forecast of our prosperity boom was unnervingly accurate. With a decade to go, the U.S. is already six times as rich in real GDP per capita terms as on the eve of 1930.

Improvements in the technology of domestic appliances has meant that traditional “household work” — the basics of laundry, cooking, and cleaning — have fallen time-wise from being a near full-time occupation (38 hours) in 1930 to just 15 hours in 2015. If Keynes’ prediction had been about chores, he hit the bullseye.

What he got wrong was what technology and innovation would mean for paid working hours. Yes, full-time production workers’ average hours have fallen from 48 hours to 40 hours since 1930. Productivity improvements, in other words, delivered a whole extra day off, as we saw the birth of the modern weekend. As a result of more part-time and flexible work, an average employed person’s working hours have fallen from 38 hours per week in 1950 to 34 hours per week in 2014 too. Yet we are clearly nowhere near the 15-hour work week he projected.

Keynes severely underestimated that, when free to choose, most of us seek further material advancement and betterment, and value the inherent dignity that comes from productive labor in the service of others. As progress raises wages, the opportunity cost of leisure rises. Faced with this trade-off, we still maintain substantial hours of employment.

This search for greater material well-being is not some moral failing, as Keynes implied. In fact, it’s precisely this yearning for a better life that has driven progress in the past 250 years. Most people are not content with modestly rising living standards driven by technological improvements producing slightly more with fewer and fewer workers, allowing us to “have fun.” They want to enjoy the best goods, services and experiences possible for their families. They want to feel the dignity of their services being needed. They want to see their living standards propelled.

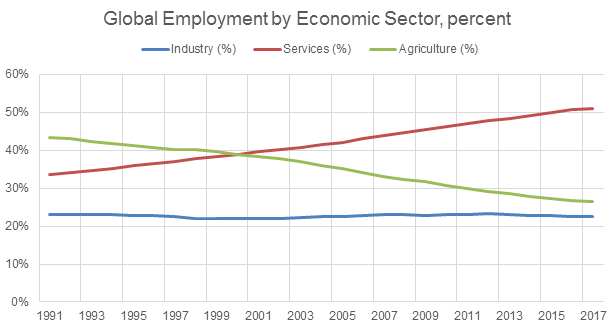

If predictions about automation are correct, then the next 30 years could well see rapid improvements in technology, as Ma implies. Service sector employment could be revolutionized, with lots of tasks currently undertaken by lawyers or doctors ripe for automation or being replaced with artificial intelligence or robotics. This will make us rich, and disrupt established occupations and work patterns. From a policy perspective, that will bring demands for jobs to be protected and innovations restrained. Predictions of “mass worklessness” will feed calls for huge social programs too, whether universal basic income us or government project jobs to give people meaningful purpose.

But the past century shows we shouldn’t fear technological change, nor presume its labor market effects will have vast destructive social consequences or change who we are. As the opportunity for leisure time and greater comfort has risen, we’ve maintained our desire for betterment and meaningful labor. That shows there’s no discrepancy between employment and “being human beings.” Striving and toiling is part of who we are.

Contra Ma and Keynes, then, I doubt increased productivity will result in mass karaoke singing. We will enjoy more comfort and the option of more family and leisure time, yes. But the recent past suggests that workers will shift into jobs delivering new entrepreneurial pursuits, into meaningful vocational activities, and new jobs where human contact and effort are highly prized by further enriched customers.

This first appeared in Medium.