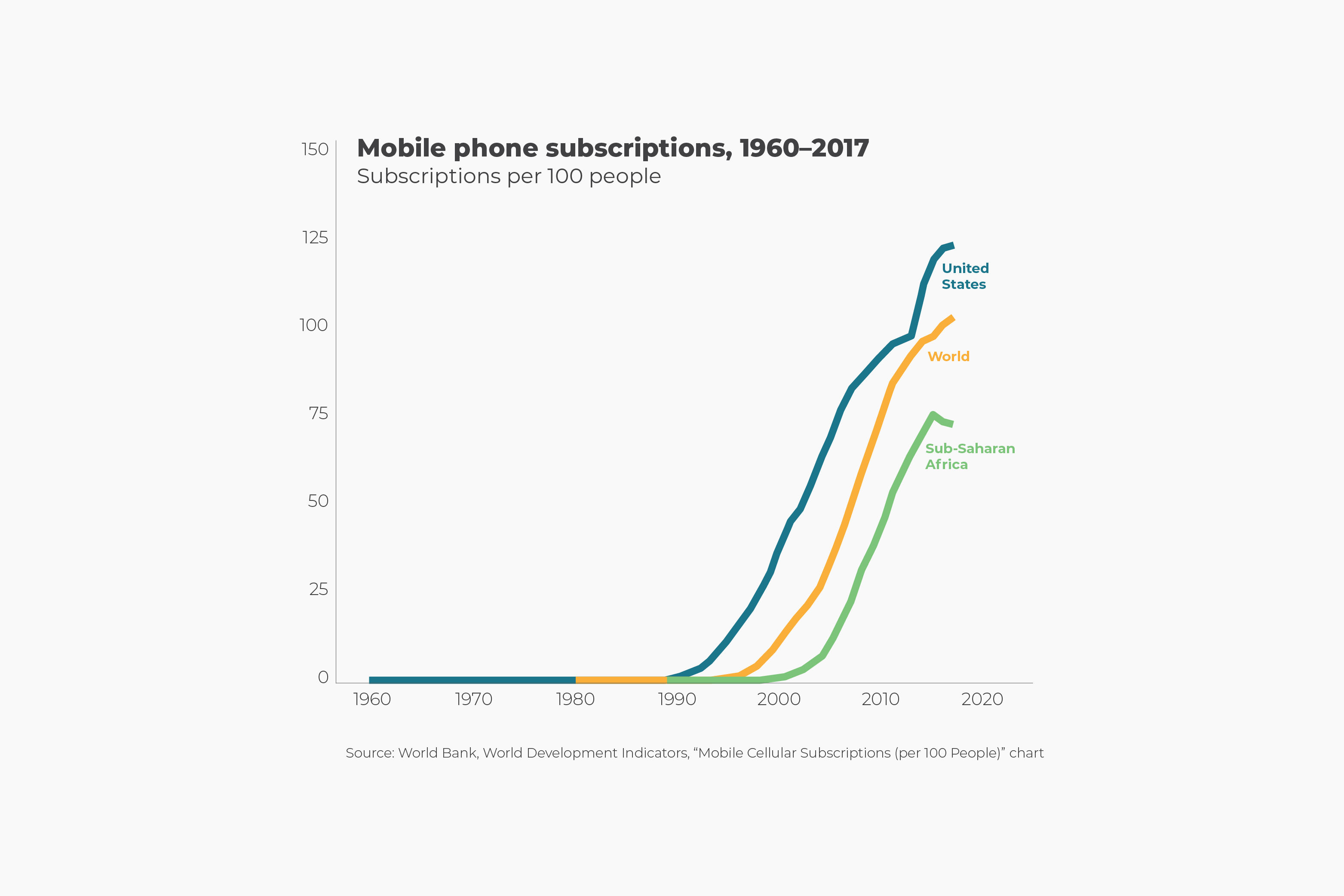

In the 1987 Oliver Stone movie Wall Street, Gordon Gekko, an immensely wealthy investor played by actor Michael Douglas, walks on a beach, watching the sunrise and talking on his Motorola DynaTac 8000X cellphone. When it was released in 1983, DynaTac was the world’s first handheld mobile phone. It weighed two pounds, took 10 hours to charge and offered 30 minutes of talk time. In 1984, the phone cost $3,995. That’s $10,277 in 2018 dollars. As late as 1990, cellphones were so expensive that only 2 percent of Americans owned them. Today, cellphones in the United States outnumber people.

Over time, cellphones became more powerful and useful. They also became smaller and cheaper. In 2016, 73 percent of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa, the world’s poorest region, owned what was once a plaything of the superrich. A Nigerian coal miner in South Africa can use a phone app to send money to his mother in Lagos. A Congolese fisherman can be warned about approaching inclement weather. A Masai herdsman can find out the price of milk in Nairobi.

By adopting cellular technology, poor countries were able to leapfrog an important bottleneck in their economic development, the landline phone. Globally, fixed phone line coverage peaked at 21.4 percent in 2002. In Sub-Saharan Africa, fixed phone line coverage never reached more than 1.57 percent of the population. Today, all of humanity’s knowledge can be accessed via cellphone easily and instantaneously.

Finally, consider the impact of cellular technology on politics. From the Arab Spring in 2010 to the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong in 2014, cellphones, smartphones, and a variety of social media apps enabled ordinary people to access censored content and to share it. Cellular technology enables the citizenry in authoritarian countries to communicate in encrypted ways and to organize.