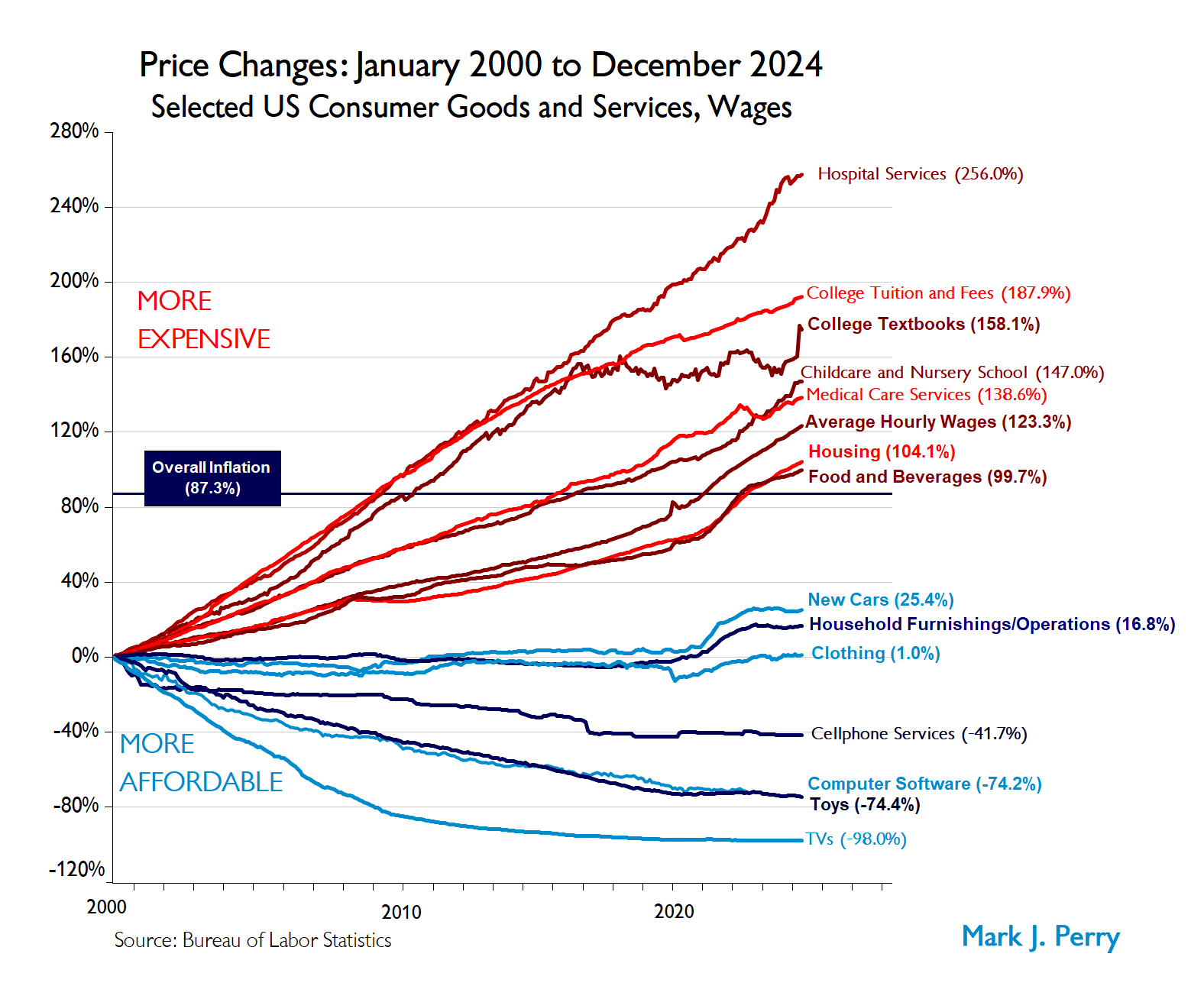

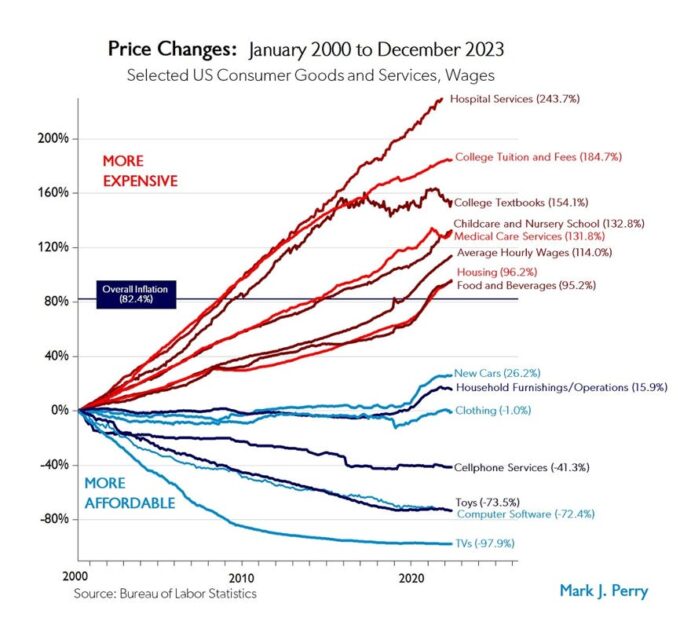

Mark Perry, an economics professor at the University of Michigan, regularly publishes a chart illustrating the percentage change in the nominal prices of a variety of US consumer goods and services. He also notes the change in average hourly wages. His data come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is a great chart, but note that prices can increase to infinity but can only decrease by 100 percent (and then they become free).

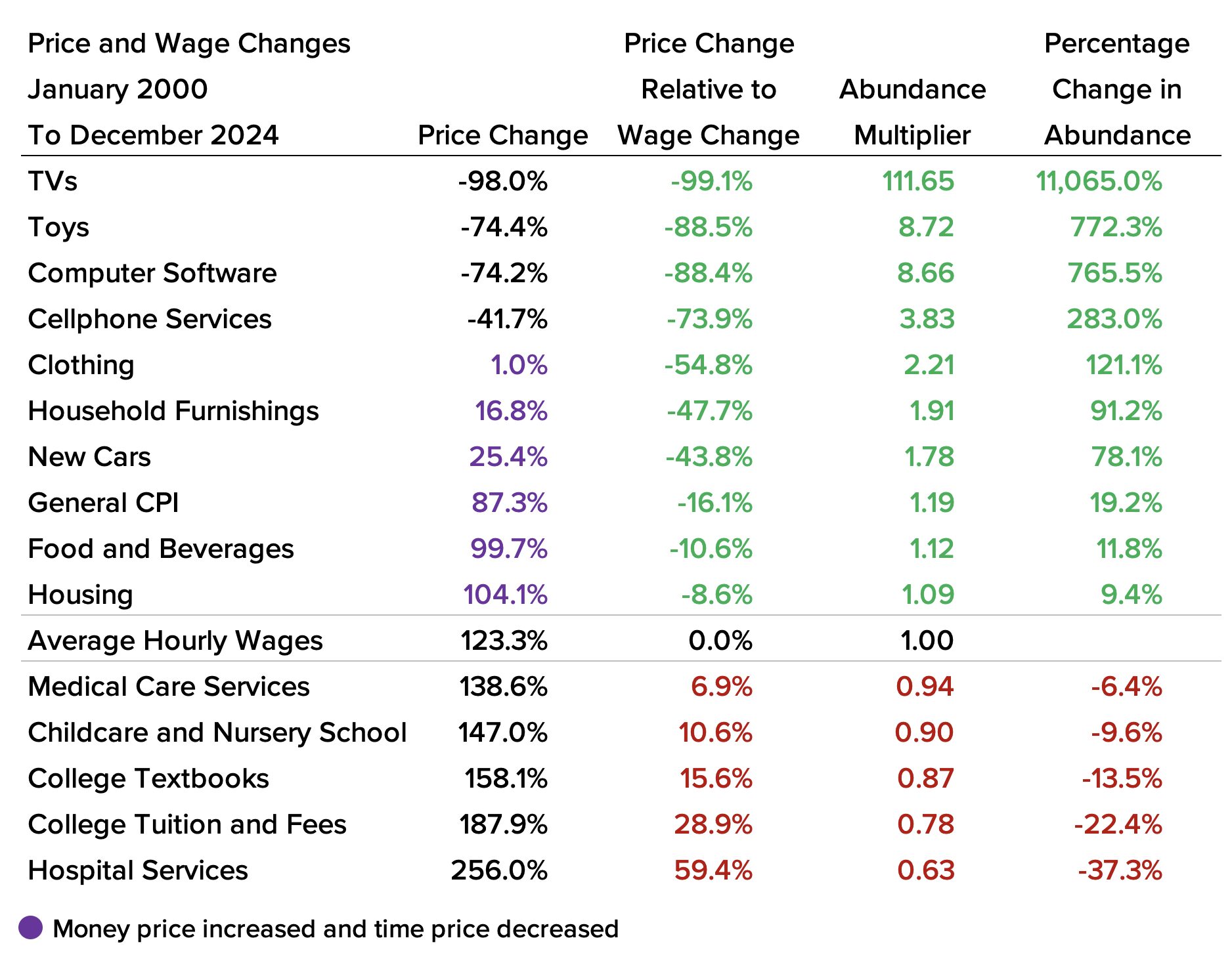

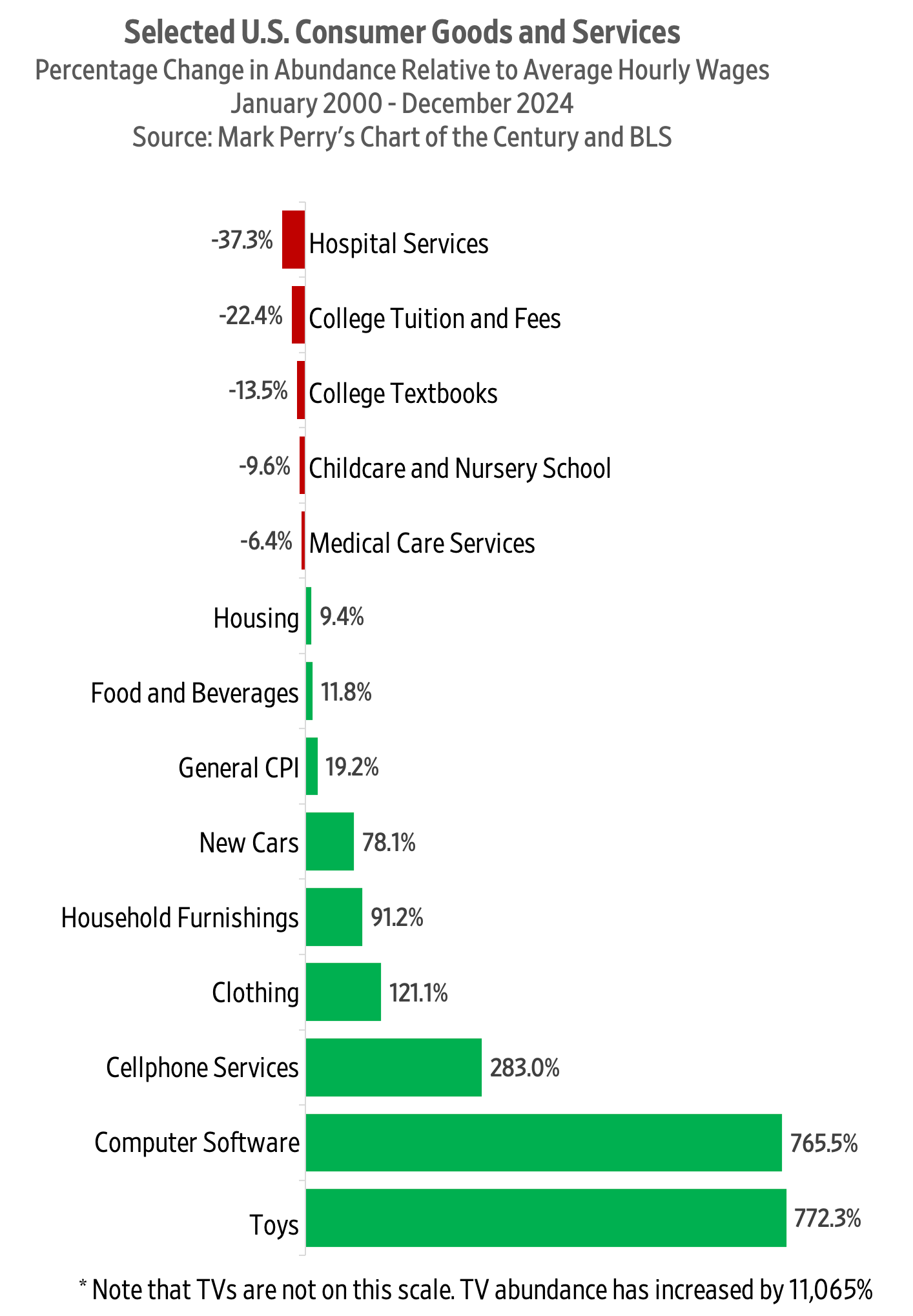

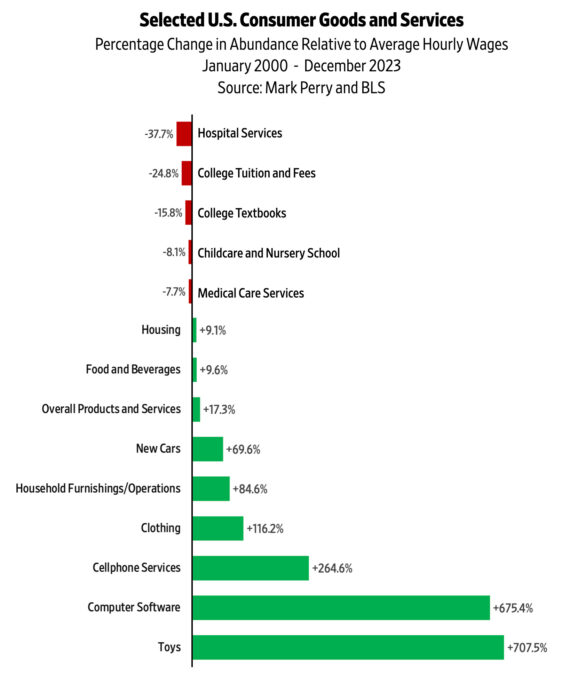

We have compared each product to the change in average hourly wages to get the change in the time prices. The times prices are then compared over time to measure changes in abundance. This bar chart illustrates these changes.

Products and services that became less abundant are subject to high levels of government interference on both the demand and supply sides.

This chart does not include TVs. The time price of TVs decreased by over 99 percent. For the time it took to earn the money to buy one TV in 2000, you can get 101.9 TVs today. TV abundance increased by 10,090 percent. The horizontal scale would be 12 times wider if we included TVs, and everything else would look tiny.

Over this 23-year period, overall inflation increased by 82.4 percent while average hourly income increased by 114 percent. Hourly income increased 38 percent faster than prices. This indicates a 14.8 percent decrease in overall time prices. You get 17.3 percent more today for the same amount of time 23 years ago.

This illustrates the fact that things can get more expensive and more affordable at the same time. As long as hourly wages are increasing faster than product prices, time prices are decreasing, which is another way of saying personal abundance is increasing.

The iPhone also is not included in this chart. In 2000, the iPhone was seven years away. It is difficult to measure how much abundance this innovation has created. To get an idea, ask yourself how much someone would have to pay you to never use a mobile phone again. Yes, you are a multimillionaire.

Time prices are a better way to measure standards of living. To really understand our economy, we must move beyond thinking in dollars and cents to thinking in hours and minutes. Time prices are the true prices.

This article was published at Gale Winds on 1/31/2024.