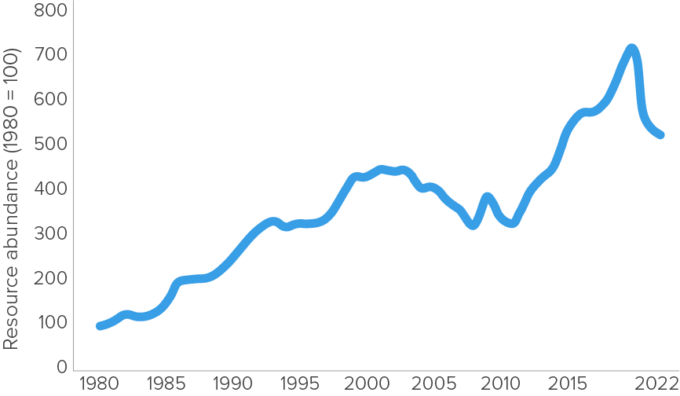

Does population growth lead to greater resource scarcity, as argued by the English scholar Thomas Malthus and, more recently, by the Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich? Or does population growth coincide with—and even contribute to—greater resource abundance, as the University of Maryland economist and Cato Institute senior fellow Julian Simon has argued? The Simon Abundance Index (SAI) measures the relationship between population growth and the abundance of 50 basic commodities, including food, energy, materials, minerals, and metals.

Main Findings

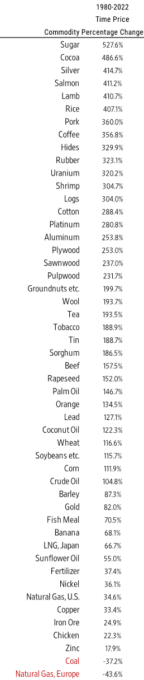

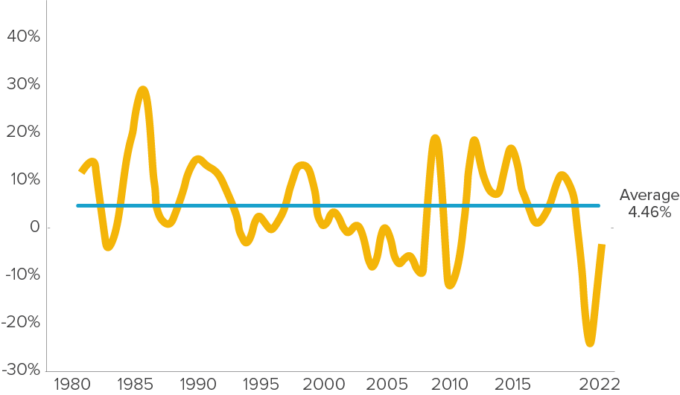

Global resource abundance fell by 3.55 percent in 2022, according to the sixth annual Simon Abundance Index. The base year of the index is 1980, and the base value of the index is 100. In 2022, the index stood at 520.1. In other words, the index rose by 420.1 percent over the last 42 years, implying a compound annual growth rate in global resource abundance of 4 percent and a doubling of global resource abundance every 17.65 years.

Figure 1: The Simon Abundance Index (1980–2022)

Analysis

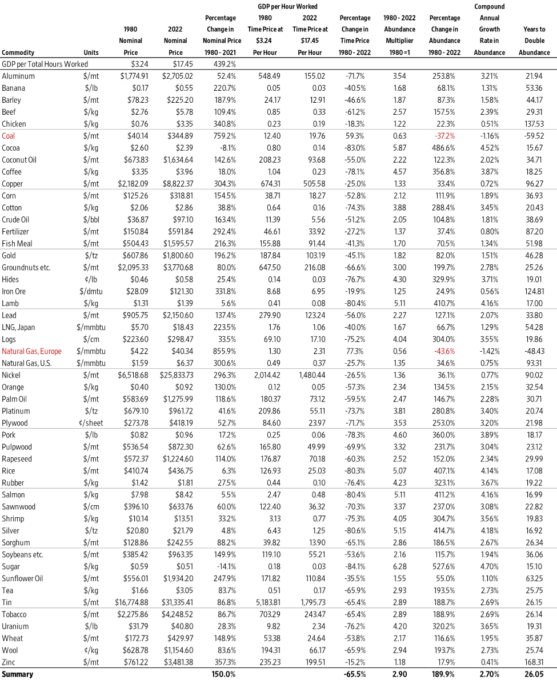

The SAI is measured in time prices. To calculate a commodity’s time price, the nominal price of a commodity is divided by the average global nominal income per hour worked. Over the last 42 years, the average of the nominal prices of the Basic 50 commodities rose by 150 percent, while the average global nominal income per hour worked rose by 439.2 percent. That means that the time price of the Basic 50 commodities fell by a geometric average of 65.5 percent.

The personal resource abundance multiplier is calculated by dividing the average of the time prices of the Basic 50 commodities in 1980 by the average of the time prices of the Basic 50 commodities in 2022. The multiplier tells us how much more of a resource a person can get for the same hours of work between two points in time. Given that the average of the time prices of the Basic 50 commodities fell by 65.5 percent, the same number of hours of work that bought one unit in the basket of the Basic 50 commodities in 1980 bought 2.9 units in the same basket in 2022.

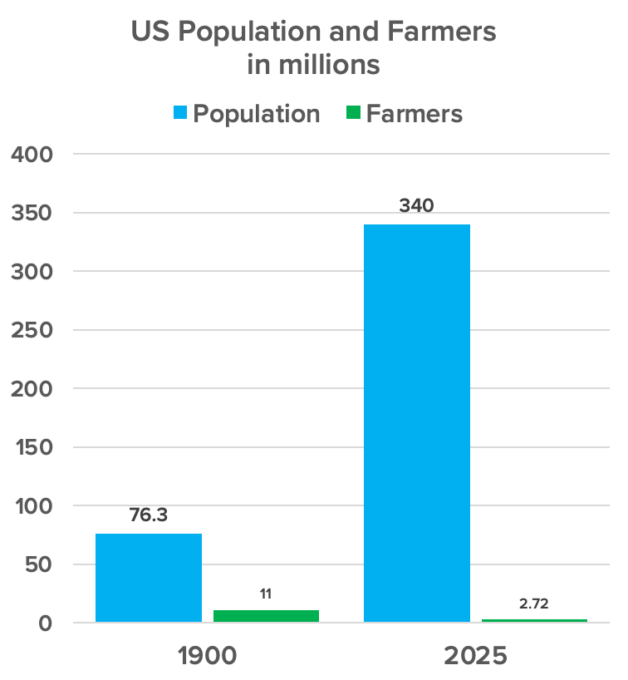

That means that personal resource abundance of the average inhabitant of the planet rose by 190 percent between 1980 and 2022. The compound annual growth rate in personal resource abundance amounted to 2.7 percent, implying that personal resource abundance doubled every 26 years.

While the average of the time prices of the Basic 50 commodities fell by 65.5 percent, the world’s population increased by 79.4 percent. So, for every 1 percent increase in the world’s population, the average of the time prices of the Basic 50 commodities fell by 0.825 percent (-65.5 percent ÷ 79.4 percent = -0.825).

Note that the personal resource abundance analysis looks at resource abundance from the perspective of an individual human being. The question that we aim to answer is: “How much more abundant have resources become for the average inhabitant of the planet?”

Population resource abundance analysis, in contrast, allows us to quantify the relationship between the overall (or global) resource abundance and the overall (or global) population growth. You can use a pizza analogy to consider the difference between the two levels of analysis. Personal resource abundance measures the size of a slice of pizza per person, while population resource abundance adds up all the slices to measure the size of the entire pizza pie.

Population resource abundance is calculated by multiplying the growth in personal resource abundance by the growth in global population ([1 + percentage change in personal resource abundance] x [1 + percentage change in population]). The resulting product of 5.201 (2.9 x 1.794) corresponds to the 520.1 value in the SAI 2023. Consequently, we can also say that population resource abundance increased at a compound annual growth rate of 4 percent, thus doubling every 17.65 years.

Figure 2: Visualization of the Relationship between Global Population Growth and Personal Resource Abundance of the 50 Basic Commodities (1980–2022)

Let us also say a few words about the resource abundance elasticity of population. In economics, elasticity measures one variable’s sensitivity to a change in another variable. If variable X changes by 10 percent, while variable Y, because of the change in X, changes by 5 percent, then the elasticity coefficient of X relative to Y is 2 (10 ÷ 5). A coefficient of 2 can be interpreted as a 2 percent change in X corresponding to a 1 percent change in Y.

We found that every 1 percent increase in population corresponded to an increase in personal resource abundance (the size of the slice of pizza) of 2.39 percent (190 ÷ 79.4). We also found that every 1 percent increase in population corresponded to an increase in population resource abundance (the size of the pizza pie) of 5.29 percent (420 ÷ 79.4).

Changes between 2021 and 2022

Over the last 12 months, the SAI declined from 539.3 to 520.1 or by 3.55 percent. While regrettable, last year’s decline was much smaller than the 22 percent drop in 2021, which was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and pandemic-related policies. That said, note that the index increased by an average 4.46 percent per year between 1980 and 2022.

Figure 3: The Simon Abundance Index, Annual Percentage Change (1980–2022)

Going forward we expect the SAI to start growing again in 2023. Humanity has witnessed shocks like those caused by the pandemic and experienced accompanying reductions in resource abundance before. Mercifully, history suggests that growth in the abundance of resources can be restored. The SAI, for example, grew by 28.4 percent, 20.0 percent, and 19.3 percent in 1986, 1985, and 2009, respectively.

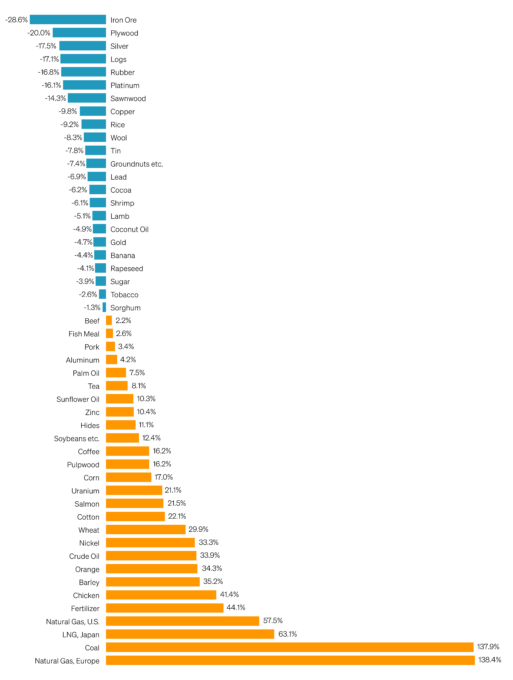

Figure 4: The Simon Abundance Index, Percentage Change in Time Prices of Individual Resources (2021–2022)

Conclusion

Despite the recent decline in SAI, resource abundance is still increasing at a faster rate than the population is growing. We call that relationship superabundance. We explore this topic in our book Superabundance: The Story of Population Growth, Innovation, and Human Flourishing on an Infinitely Bountiful Planet.

Additional Information

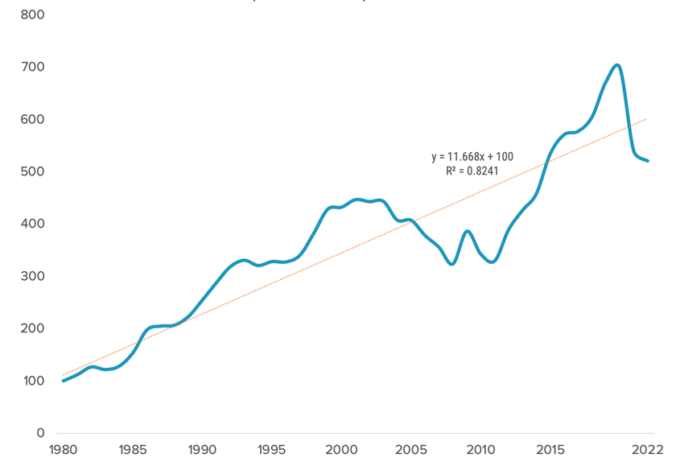

Appendix A: Alternative Figure 1 with a Regression Line, Equation, and R-Square.

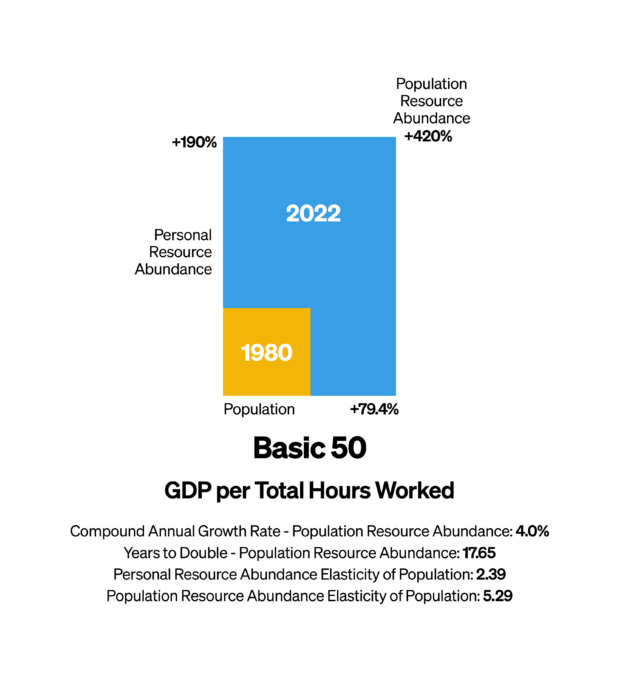

Appendix B: The Basic 50 Commodities Analysis (1980–2022)

Appendix C: The Basic 50 Commodities, Percentage Change in Personal Resource Abundance (1980–2022)