“Is it OK to still have children?” That’s a question that bothers the environmental consciousness of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY). Comedian Bill Maher thinks that he has the answer. “The great under-discussed factor in the climate crisis is there are just too many of us and we use too much s*#t. Climate deniers like to say, ‘There’s no population problem, just look out the window of an airplane. So much open space down there.’ But it’s not about space, it’s about resources. Humans are already using 1.7 times the resources the planet can support,” he recently noted. There are plenty of legitimate topics in the debate about the health of the planet, but overuse of resources is not one of them.

Humanity’s impact on the planet is deep, but that does not mean that Earth’s future is hopeless. The loss of biodiversity, as the U.N. report recently found, could become a problem, but that can be mitigated by greater urbanization and higher yield crops, thus enabling people to leave an ever-increasing portion of the countryside to flora and fauna. Pollution of rivers, lakes and oceans, which is partly driven by overuse of fertilizer and pesticide in agriculture, could be mitigated by genetically-modified crops that require little of either. Overabundance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the threat of global warming could be mitigated through nuclear power production.

The one concern that we believe people do not have to worry about is the overuse of resources. Late last year, we co-authored a study titled, The Simon Abundance Index: A New Way to Measure Availability of Resources. In that paper we looked at the prices of 50 foundational commodities covering energy, food, materials and metals. Between 1980 and 2017, our findings showed, resources have become substantially more abundant. Our calculations confirmed the insights of the University of Maryland economist Julian Simon who observed in his 1981 book The Ultimate Resource that humans are intelligent beings, capable of innovating their way out of shortages through greater efficiency, increased supply, and the development of substitutes.

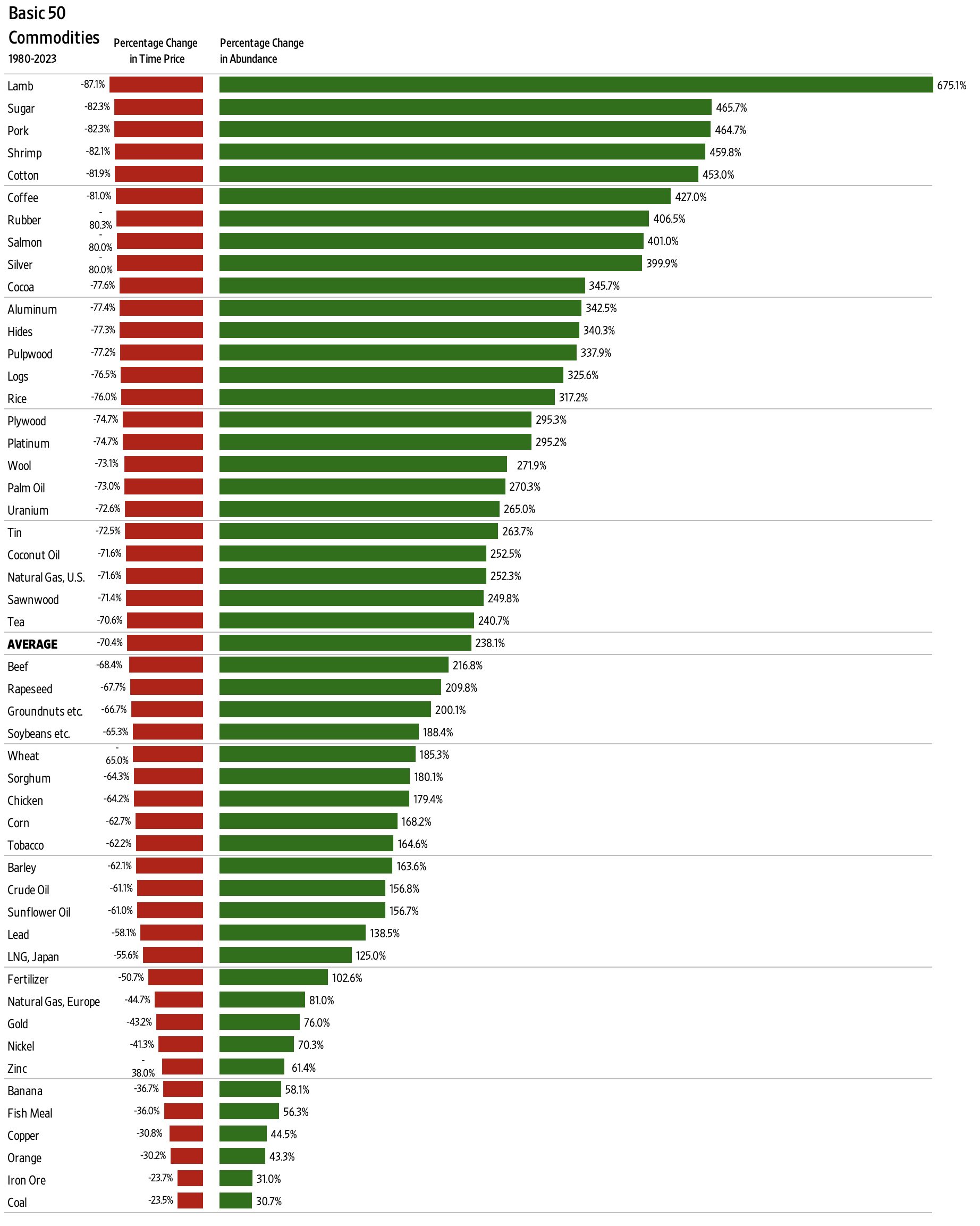

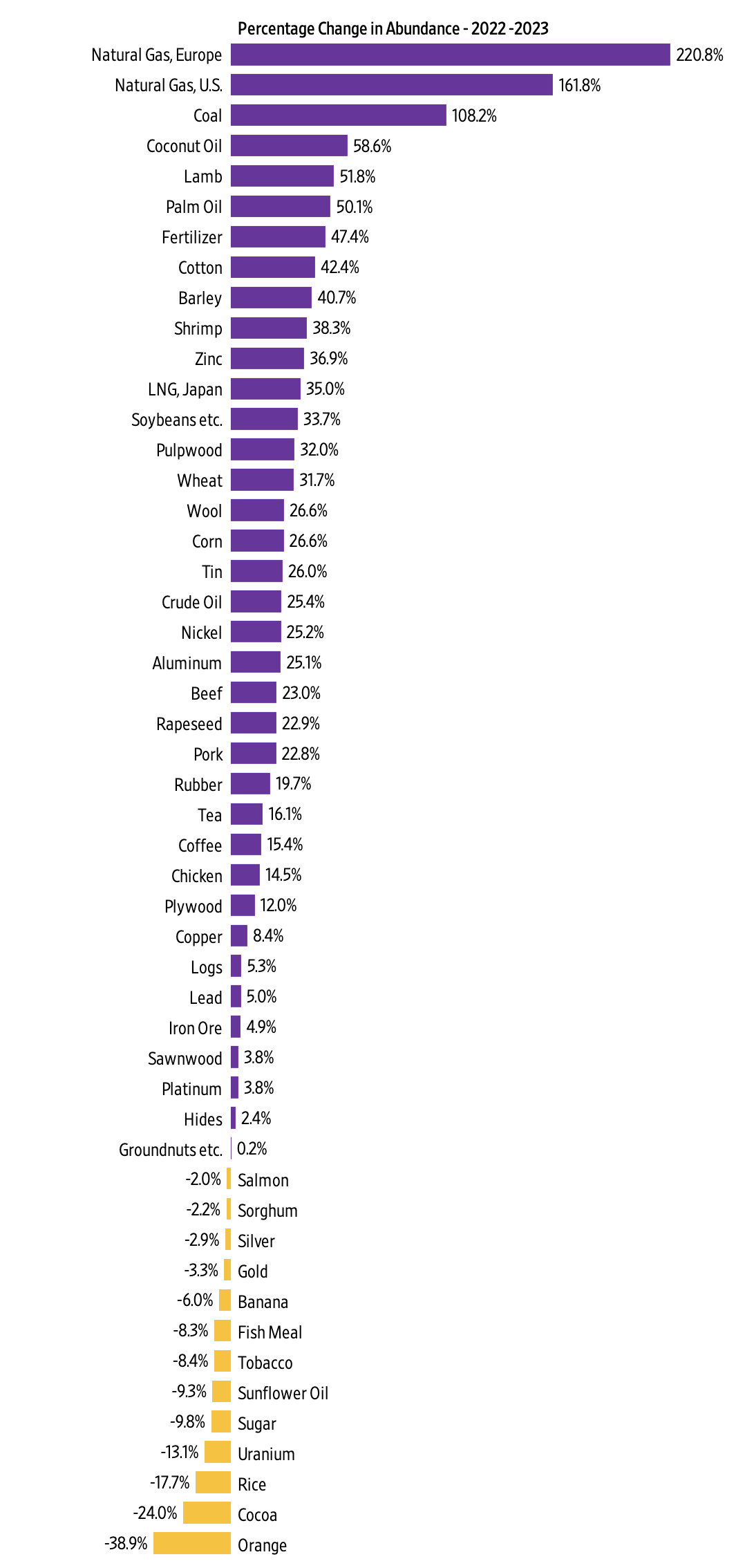

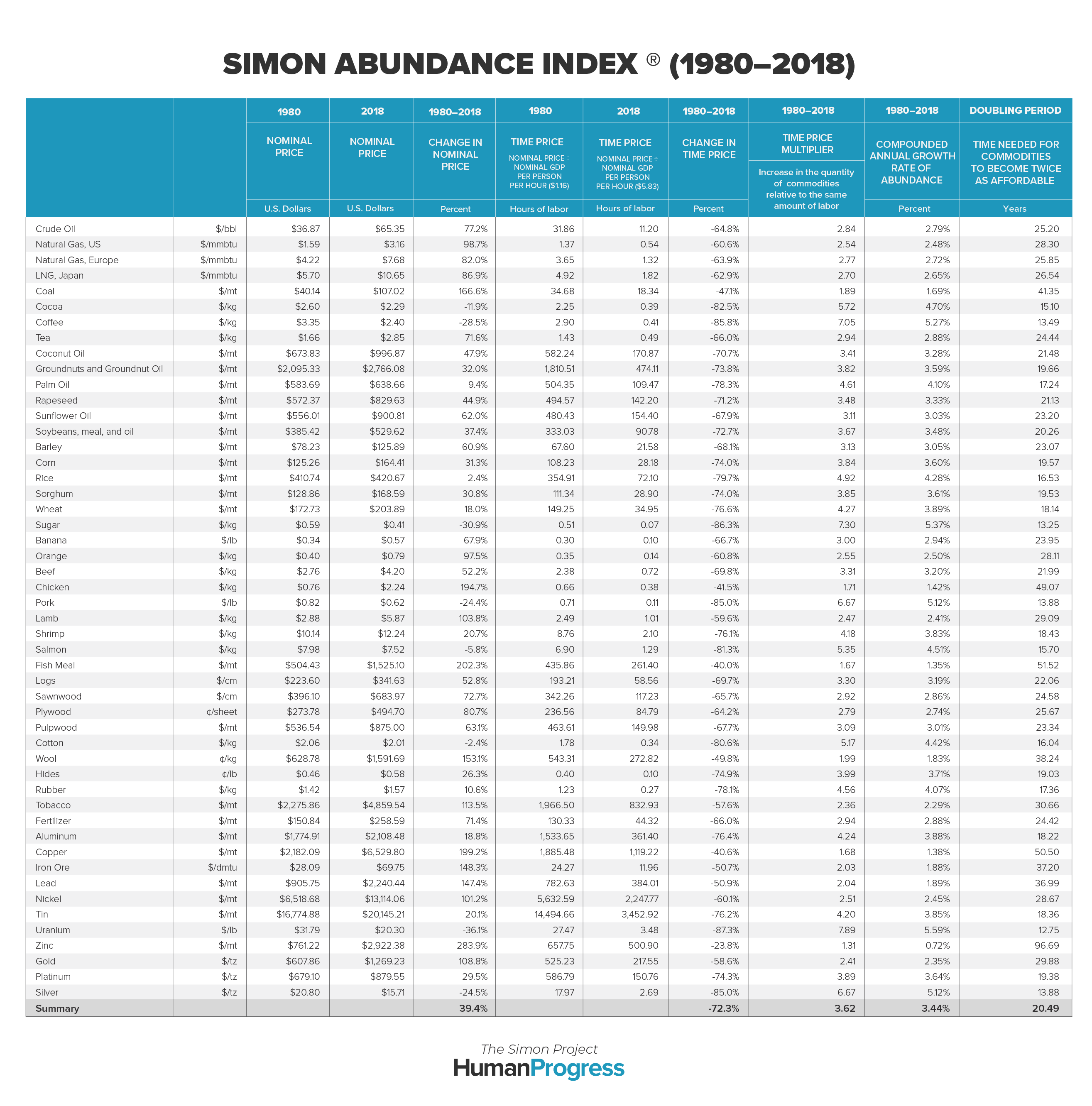

To arrive at our conclusions, we have come up with four new concepts: Time Price, Price Elasticity of Population, the Simon Abundance Framework and Simon Abundance Index ®. Today marks the second installment in what we hope will become an annual update of the relationship between population growth and resource availability. As was the case last year, we have looked at the prices of 50 basic commodities tracked by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (see Figure 1). The Simon Abundance Index ® 2019 covers the time period between 1980 and 2018.

Figure 1

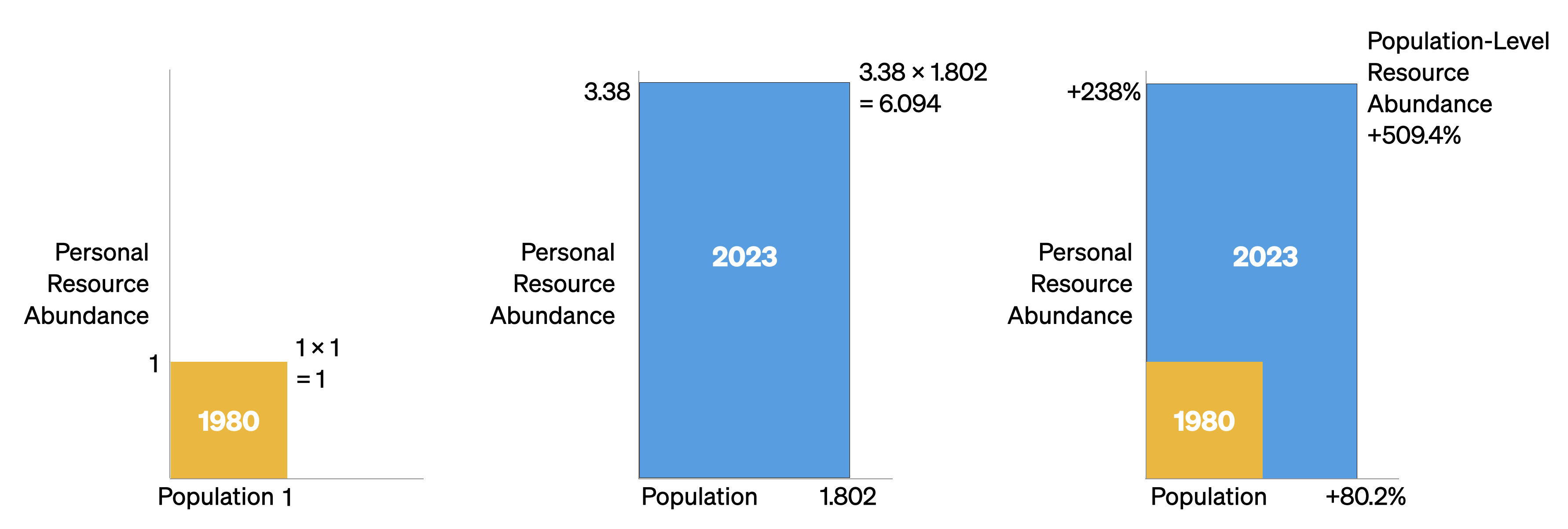

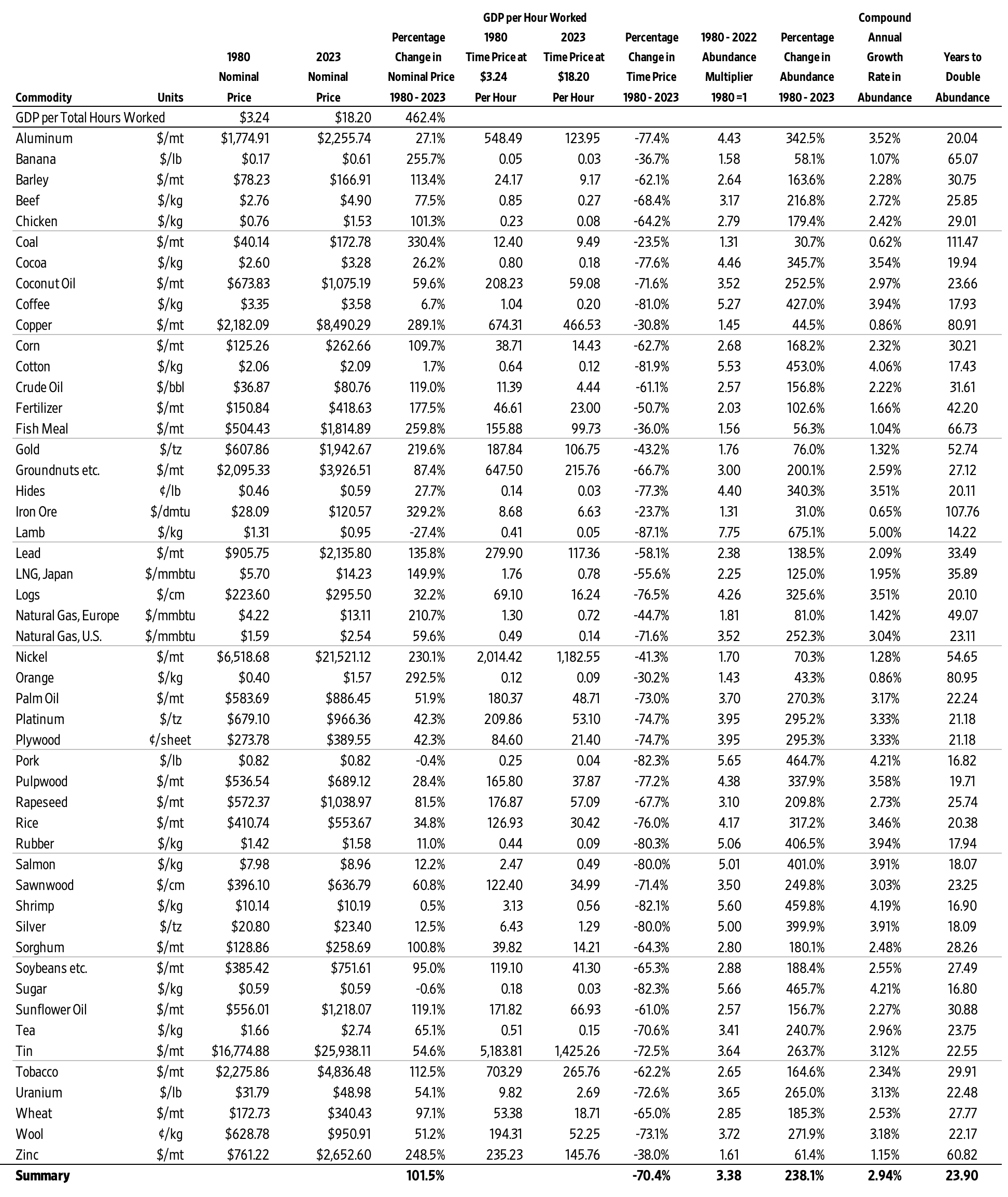

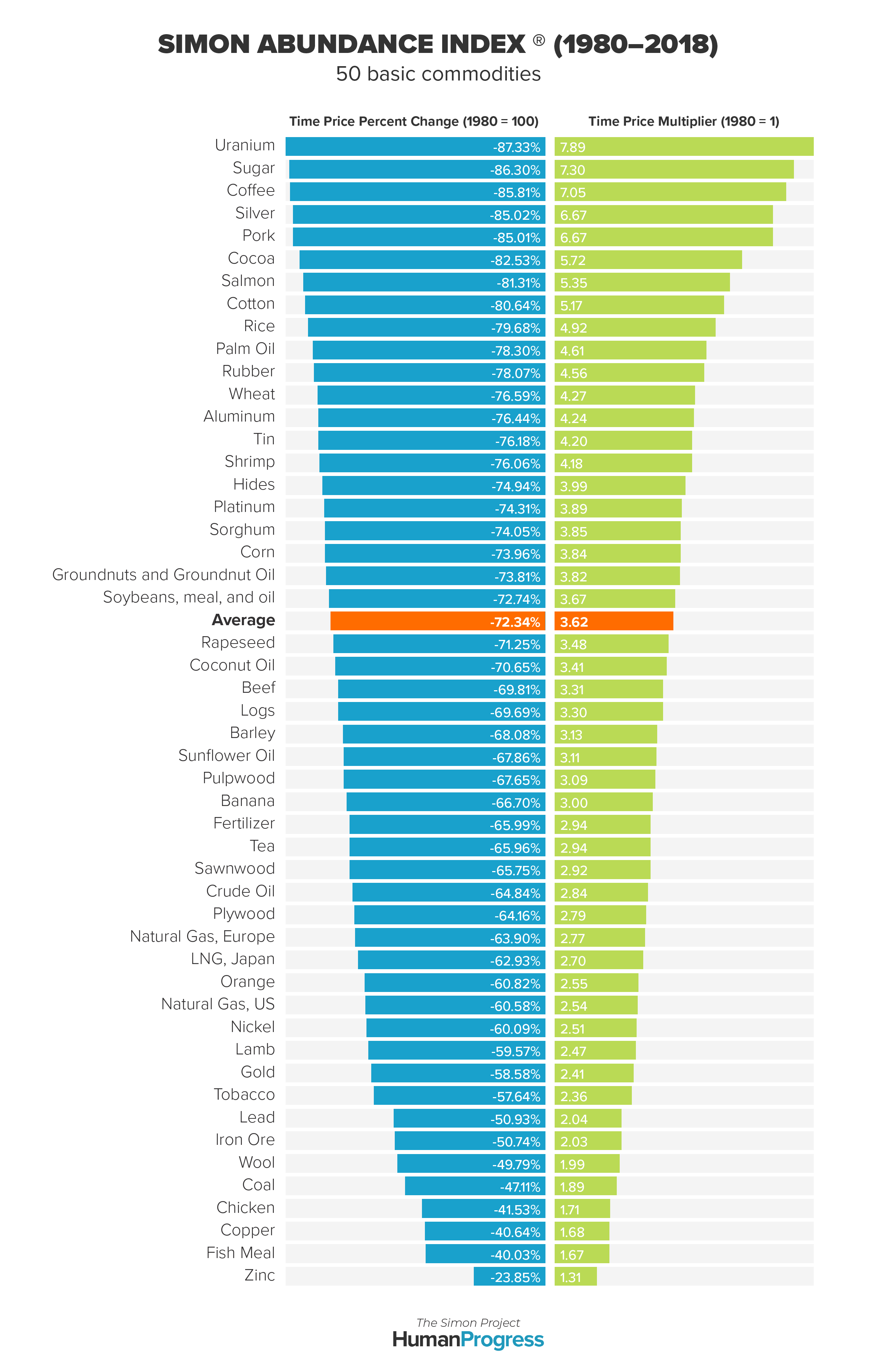

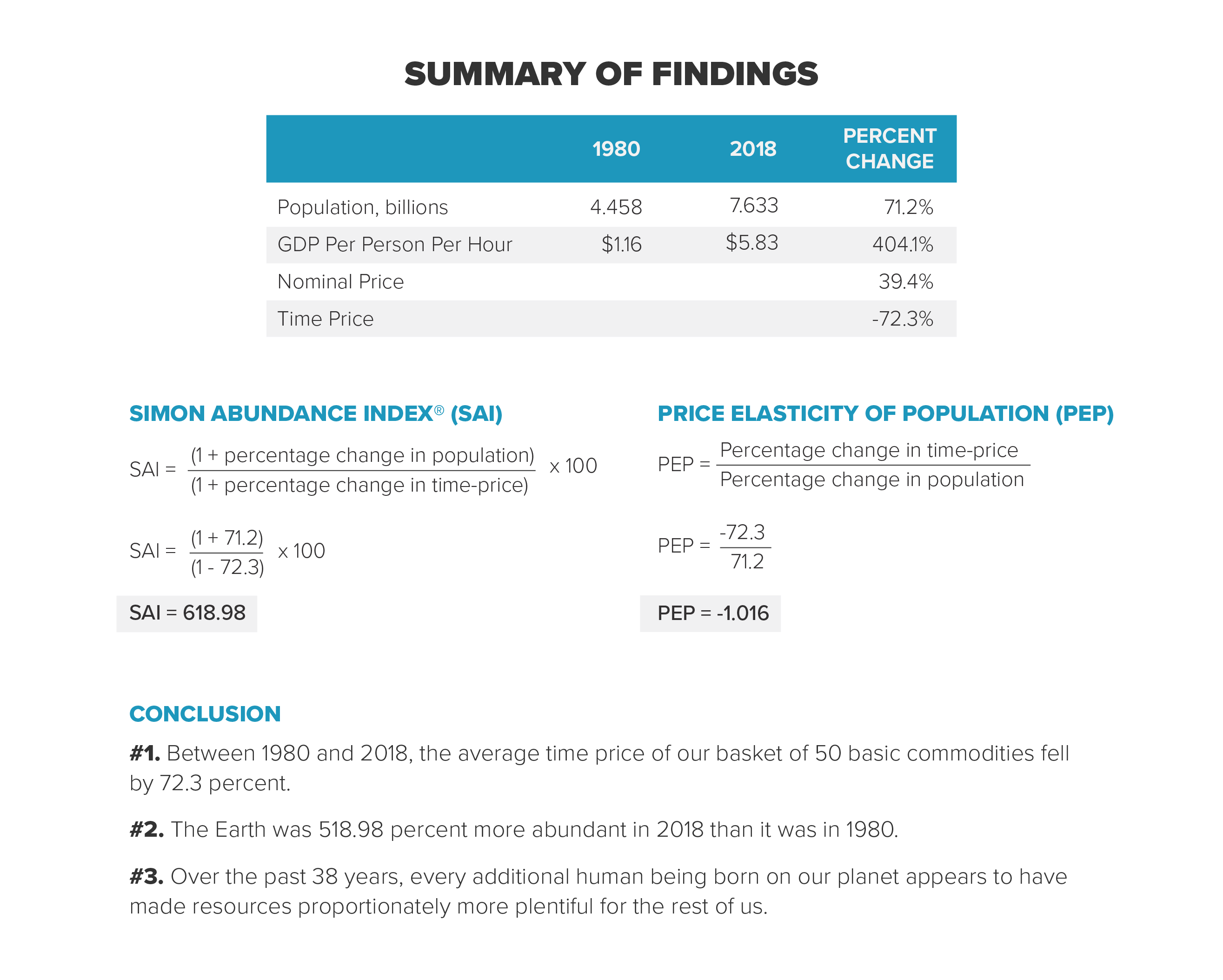

The time price denotes the amount of time that a person has to work in order to earn enough money to buy something. To calculate the time price, the nominal money price is divided by nominal hourly income. (We got the latter dataset by combining the World Bank’s average global GDP per person with the Conference Board’s estimation of annual hours worked.) Between 1980 and 2018, the average time price of our basket of 50 basic commodities fell by 72.3 percent. The time it took to earn enough money to buy one unit in that basket of commodities in 1980 bought 3.62 units in 2018 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

The price elasticity of population (PEP) allows us to measure sensitivity of resource availability to population growth. Between 1980 and 2018, world’s population increased by 71.2 percent. The time price of commodities fell by 72.3 percent. As such, the time price of commodities declined by 1.016 percent for every 1 percent increase in the world’s population. Put differently, over the last 38 years, every additional human being born on our planet appears to have made resources proportionately more plentiful for the rest of us.

The Simon Abundance Framework uses the PEP values to distinguish between different degrees of resource abundance, from decreasing abundance at one end of the spectrum to superabundance at the other end. Considering that time price of commodities decreased at a faster proportional rate (-72.3 percent) than population increased (71.2 percent), we conclude that humanity is experiencing superabundance.

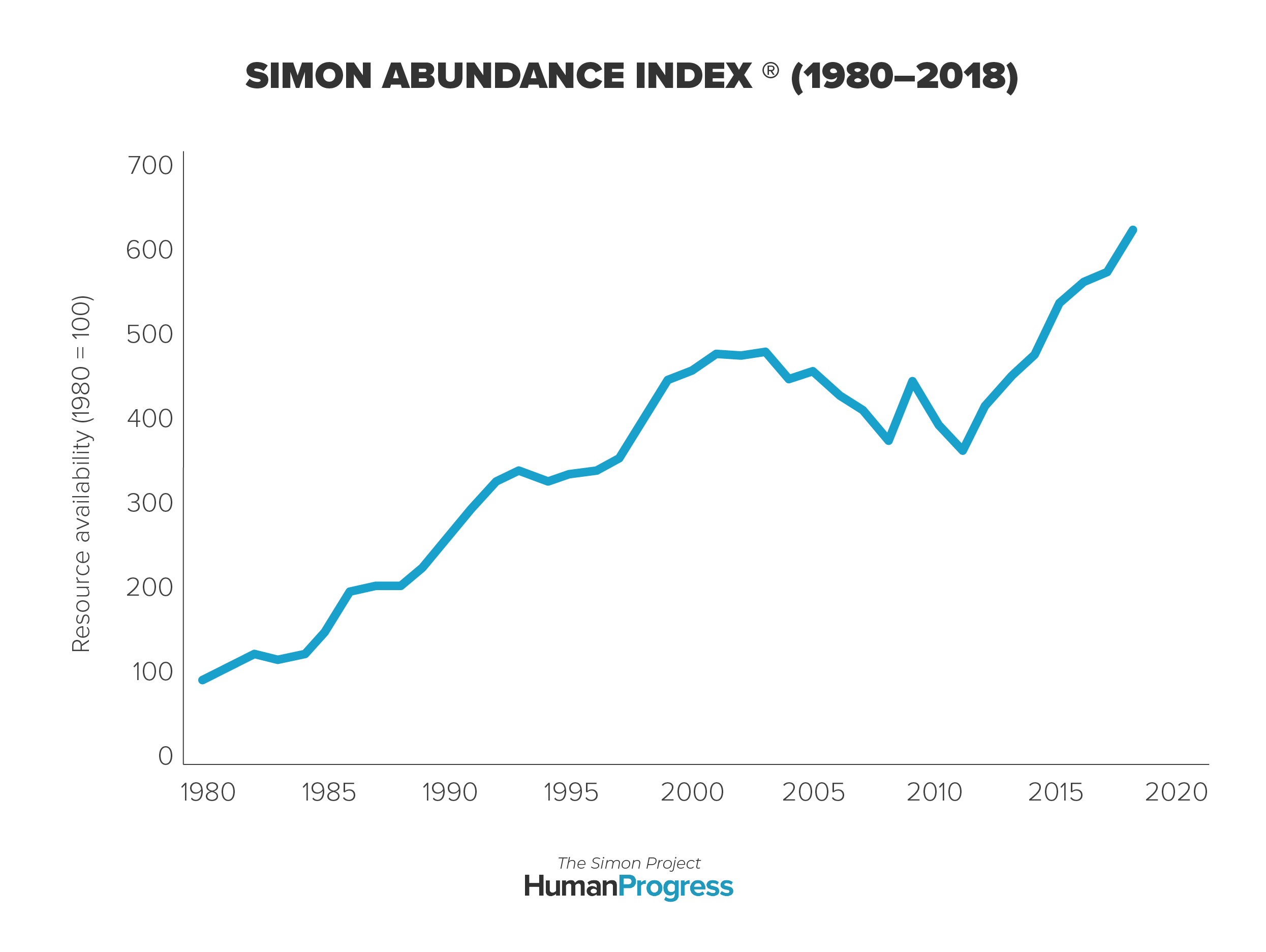

Finally, The Simon Abundance Index ® 2019 uses the time price of commodities and change in global population to estimate overall resource abundance. The Index represents the ratio of the change in population over the change in the time price, times 100. It has a base year of 1980 and a base value of 100. In 2018, the Index reached a level of 618.98. That is to say that the Earth was 518.98 percent more abundant in 2018 than it was in 1980 (see Figure 3). The compounded growth rate of abundance came to 3.44 percent per annum, which means that the affordability of our basket of commodities doubled every 20.49 years.

Figure 3

Simon’s revolutionary insights with regard to the mutually beneficial interaction between population growth and availability of natural resources, which our research confirms, may be counterintuitive, but they are real. The world’s resources are finite in the same way that the number of piano keys is finite. The instrument has only 88 notes, but those can be played in an infinite variety of ways. The same applies to our planet. The Earth’s atoms may be fixed, but the possible combinations of those atoms are infinite. What matters, then, is not the physical limits of our planet, but human freedom to experiment and reimagine the use of resources that we have.

Notes on our methodology

Since last year, we have tweaked our methodology to make The Simon Abundance Index ® simpler and more robust. The most important change is that we no longer deflate commodity prices and income in any way. Economists differ on what kinds of deflators are appropriate. Moreover, deflators are unnecessary. Thus, in this year’s index, we arrive at our time prices, which underpin all of our subsequent calculations and findings, by simply dividing the nominal price of a commodity by the nominal hourly wage in 1980. We do the same for 2018.

Note that the Index deals with global prices of commodities relative to the average global GDP per capita per hour. We recognize that GDP figures are not the same as wages. Unfortunately, a global hourly wage is tough to calculate – people work different numbers of hours, economies are composed of different kinds of workers, the proportion of non-wage compensations differs, etc. As such, GDP per capita per hour remains the best approximation of global hourly income. That said, what matters for our analysis is not the exact income level, but the ratio of change over time.

To learn more, visit humanprogress.wpengine.com/simonproject.