Summary: The modern world is built on centuries of progress, yet many take its comforts and opportunities for granted. A new movement aims to redefine our understanding of advancement, and focuses on celebrating humanity’s achievements to shape an optimistic narrative for the future. From fostering technological innovation to advocating for economic growth, this coalition strives to combat cultural pessimism and inspire a renewed belief in the potential for a better world.

“The tragedy of today is that we are the heirs and the beneficiaries of thousands of years of progress and we take it for granted. You wake up in a nice soft bed. You go get fresh milk and orange juice from the fridge. You take a shower under hot running water. You hop on the train or car to work. You take the elevator up to the 40th floor. You earn your living by typing on a computer behind big plate glass windows in an air-conditioned building. You relax in the evening by streaming movies and music or catching up with friends from around the world in your real-time video calls. None of this existed a couple centuries ago. A lot of it didn’t exist a few decades ago. And yet it’s just so easy to go through your days enjoying all of that without giving a second thought to where it all came from or how, or how challenging it was to bring all of those amazing inventions into the world.”

Jason Crawford, founder of the Roots of Progress project, is one of the leaders of a new pro-progress movement that is coalescing in a collection of think tanks, websites, and other intellectual incubators. It celebrates humanity’s achievements so far. It judges progress not in technocratic terms but with an eye on outcomes for individual human beings. And it imagines, again in Crawford’s words, an “ambitious technological future that we want to live in and are excited to build.”

Rethinking Progress

These groups promoting economic growth spurred by scientific, technological, and industrial progress are quite distinct from modern political progressives. Contemporary progressives trace their ideological lineage back to the Progressive movement that arose in American politics around the turn of the 20th century as a response to the consequences of mass urbanization, mass immigration, increasing economic inequality, and rapid industrial growth.

Fundamental then as it is today among modern progressives is their certainty that they know the direction in which “progress” must go and that exercise of government power guided by a technocratic elite is central to achieving their version of “progress.” Princeton University historian Thomas C. Leonard observes that early 20th century “progressives believed in a powerful, centralized state, conceiving of government as the best means for promoting the social good and rejecting the individualism of (classical) liberalism.” In addition, he says, they believed in “the disinterestedness and incorruptibility of the experts who would run the technocracy they envisioned, and a faith that expertise could not only serve the social good, but also identify it.”

A hundred years later, one illustrative distillation of modern progressivism is “The Progressive Promise” manifesto issued by the 101 members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. “We believe that government must be the great equalizer of opportunity for everyone,” forthrightly states the Promise. “We support bold policies to close the gap between the rich and everyday Americans and ensure our government delivers essential services to every person in this country.” They envision “transformational change” that includes “ending poverty and income inequality,” and “advancing racial justice and equity in every policy.” It is notable that unlike their early 20th century forebears’ belief in technological progress and economic growth, this essentially redistributionist manifesto nowhere mentions policies aimed at advocating and promoting either in the 21st century. In their view, uncontrolled economic growth is leading to environmental catastrophe and to appalling social consequences.

The contours of the new progress movement stretch from the Human Progress project at the libertarian Cato Institute to the “eco-modernist” initiatives at the Breakthrough Institute and the Pritzker Innovation Fund. Four relatively new groups at the forefront of the pro-progress forces are The Roots of Progress, the Institute for Progress, The Progress Network, and Works in Progress. Together, they are—as The Progress Network puts it—”building an idea movement that speaks to a better future in a world dominated by voices that suggest a worse one.”

Cultural Pessimism

There are indeed many voices who say our future is bleak. William Rees, a population ecologist at The University of British Columbia, claimed last year that “collapse is not a problem to be solved, but rather the final stage of a cycle to be endured.” Also last year, Stanford University biologist and indefatigable population doomster Paul Ehrlich told 60 Minutes “that the next few decades will be the end of the kind of civilization we’re used to.” A 2022 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences declared that climate change could “result in worldwide societal collapse or even eventual human extinction.” Last year an article in the Journal of Industrial Ecology suggested that civilizational collapse is likely this decade and certain by 2040.

These dire prognostications are reflected in bleak public attitudes, especially in rich developed countries. A YouGov poll in 2016 found only 6 percent of Americans thought the world was getting better. Other rich countries had even lower scores: Germany and the United Kingdom were at 4 percent, Australia and France at 3 percent. (The Chinese were the most optimistic, with 41 percent saying the world was getting better.) In 2017, a Pew Research Center poll reported that 41 percent of Americans thought that life today was worse than it was 50 years ago, compared to 37 percent who thought it was better.

In 2021, The Lancet published a poll of 10,000 young people (ages 16 to 25) in 10 countries (Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the U.K., and the USA) asking how they felt about climate change that found pervasive pessimism about the future. About 75 percent reported that “they think the future is frightening,” with more than 55 percent agreeing that “humanity is doomed” and 39 percent saying they are “hesitant to have children.” About 45 percent responded that “their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning.” A YouGov poll in 2022 found more than 30 percent of American adults thinking climate change will lead to extinction of the human race.

In 2023, 76 percent of Americans in an NBC survey were “not confident that life for our children’s generation will be better than it has been for us.” That same year, a Wall Street Journal poll similarly reported that 78 percent of Americans believe that life for their children will not be better than it was for themselves. A November poll by the European Council on Foreign Relations found only 24 percent of Americans were optimistic about their country’s future. These are the headwinds that the emerging progress movement is combating.

The Optimistic Opposition

There is a division of labor between the pro-progress groups. The Roots of Progress is focused on creating a new philosophy of progress and promoting young intellectuals who propound it. In an essay outlining what that might look like, Crawford argues for “a renewed vision of the future” that accelerates technological progress to provide humanity with cheap, abundant, clean fusion energy, permanent settlements in space, and cures for diseases and even aging itself using advanced biotech. “A future where we don’t just end poverty, but create new levels of wealth so fantastic that they make today’s wealth look like poverty in comparison—just as was done over the last two hundred years,” he writes.

“We are going to need a large body of intellectuals, of writers, creatives, educators, and journalists,” says Crawford. To develop this cadre, the group has created a fellowship program as “a career accelerator for progress intellectuals.” There were over 500 applicants for the first cohort, of which 19 were selected. The selected fellows analyze how to remove the regulatory roadblocks that stymie infrastructure and clean nuclear power deployment, how to incentivize countries to welcome more immigration, and how to overcome pervasive risk aversion in awarding research grants.

The Institute for Progress (IFP), co-founded by Caleb Watney and Alec Stapp, focuses on finding public policy ideas that can boost innovation sooner rather than later. “Because of the unique position of the United States, we have a moral call to really take the lead and embrace our role as the world’s R&D lab,” argues Watney. The U.S., he notes, has particular advantages when it comes to scientific and technological progress: the concentration of the world’s top universities, the fact that the world’s top scientific minds want to immigrate here, a huge and dynamic economy that enables the rapid iteration and prototyping of new technologies.

“The Institute for Progress is not an organization focused on mass politics,” Watney adds. “We are not going to get people to hold up banners saying, ‘I want total factor productivity growth to be higher.'” Instead, it’s “a very incrementalist organization” that looks “for issues that are important. If you were to change them, would they really matter? Are they tractable? Does it seem like you could actually move the needle on them in a useful way in, say, the next five years?” Among other activities, IFP researchers engage in such nitty-gritty work as filing detailed comments on federal agency proposals. For example, the IFP recently advised the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority on how to hasten the development of more effective coronavirus vaccines. Also, the IFP signed an agreement last year to partner with the National Science Foundation to help the agency develop faster mechanisms for funding high-risk, high-reward research proposals.

Meanwhile, Works in Progress publishes long-form case studies on how entrepreneurs, inventors, researchers, and others have successfully made progress in fixing various problems. It also prints proposals for how to ameliorate those still unresolved. Among the topics covered in recent articles: overcoming obstacles to tapping geothermal energy, upzoning in New Zealand to address housing shortages, how advance market commitments could have spurred the development of an effective malaria vaccine more quickly, and—in an article by Reason‘s own Peter Suderman—how mixologists surmounted the problem of boring drinks.

The Progress Network—based at New America, a liberal-leaning think tank—aims to bring together an ideologically diverse set of pro-progress scholars and pundits. Its founder, money manager Zachary Karabell, says he’s aiming to “create a cohort of people who are united by a sensibility, but certainly not united by a monolithic view of what’s working and what isn’t.” Its cohort of associates includes the Cato Institute’s Mustafa Akyol, MIT economist Erik Brynjolfsson, George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen, Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, journalist Matthew Yglesias, Columbia University linguist (and New York Times columnist) John McWhorter, Depolarization Project CEO Alison Goldsworthy, and Pritzker Innovation Fund chief Rachel Pritzker. Other Network members include the founders of both The Roots of Progress and the Institute for Progress. Karabell ruefully acknowledges that it is hard to get the independent “idea entrepreneurs” he has recruited into the Progress Network to collaborate. For now, the Network has assembled 120 or so members whose voices make the constructive point that the world, on the whole, is getting better. The Network highlights stories detailing the actuality of progress “from around the world that get kind of buried under the avalanche of negative stories” through its What Could Go Right? podcast, a daily newsletter, and social media.

The heads of all four organizations cite the animating influence of the July 2019 Atlantic article “We Need a New Science of Progress,” written by Cowen and Patrick Collison, the billionaire founder of the internet payments company Stripe. “The success of Progress Studies will come from its ability to identify effective progress-increasing interventions and the extent to which they are adopted by universities, funding agencies, philanthropists, entrepreneurs, policy makers, and other institutions,” Cowen and Collison argued. “In that sense, Progress Studies is closer to medicine than biology: The goal is to treat, not merely to understand.”

Cowen and Collison are involved in the movements in other ways too. Both The Roots of Progress and Works in Progress have received grants from the Emergent Ventures project, administered by Cowen. Works in Progress became part of Stripe Press in 2022.

How Progress Got a Bad Reputation

Why did progress fall out of favor? Crawford suggests the strong belief in economic, technological, and social improvement that characterized 19th century Europe and America was dented by the next century’s bloody world wars. “People before World War I had hoped that technology and economic growth would actually lead to an end to war and that we were entering a new era of world peace,” he says. “That proved to be disastrously wrong. Not only had technology not led to an end to war, it had actually made war all the more horrible and destructive. It had given us the machine gun, chemical weapons, the atomic bomb.”

Crawford also notes the 20th century saw the emergence of institutions featuring “top-down control by a technical elite.” This, he argues, prompted “a countercultural idea that saw progress as linked to this authoritarianism and rejected both.”

Watney points to the negative externalities that have accompanied technological development and economic growth—air and water pollution, climate change, deforestation—and suggests these have contributed to the disillusionment with progress as well. On top of that, he says, a spirit of complacency and safetyism has emerged in rich developed countries, adding new roadblocks.

“We have become the victims of our success, to a certain extent,” Watney argues. “As you get increasing levels of wealth and productivity, you’re more inclined to keep hold of the safety and the gains that you already have and less likely to risk a little bit to gain a lot more.” Or as Karabell puts it, “If you’re more worried about the unknown negative consequences than you’re excited about unknown positive consequences, you’re basically going to be sclerotic and not do anything.”

You should not confuse this appreciation for past progress with a belief that progress is complete. Karabell stresses that he doesn’t believe “we should just shut up and recognize” everything that’s going right. It’s just that “we are demonstrably able to create problems and we’re demonstrably able to solve them.”

Crawford thinks progress has slowed in recent decades. Two big reasons for the slowdown, he argues, are “the growth of the regulatory state” and “the centralization and bureaucratization of research, and in particular the funding of research.” Both impose unnecessarily constraining limits on scientific freedom and the types of opportunities and inventions that can be pursued.

“It’s totally fair to be frustrated with a lot of the excesses of the regulatory state,” says Watney. More hopefully, he adds: “If you’re so pessimistic about the current state, that means there should be lots of low-hanging fruit. Small changes could actually lead to really large increases.”

The IFP’s chief aim is to pick that low-hanging fruit by cutting down the overburden of regulation and reforming the stodgy processes that encrust science funding. So the group is working to streamline the National Environmental Policy Act so that it no longer blocks for years the building of critically needed infrastructure: roads, pipelines, electrical lines, and nuclear, renewable, and geothermal energy projects. The institute also wants to speed up the approval processes at the Food and Drug Administration and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission—in the first case to get new treatments to patients more quickly, and in the second to deploy modern nuclear reactors faster. It is pushing to reform the science funding programs at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation. For example, researchers associated with the IFP note that NIH peer review grant evaluations now tend to focus on the probability that research proposals will achieve their primary outcomes. Thus this evaluation process generally steers funding away from high-risk, high-reward research. One IFP proposal to overcome this conservative bias is to have peer reviewers first assess how valuable the new cures and treatments stemming from the proposed research would be should it prove successful in developing new fundamental knowledge.

Trying To Make It Better

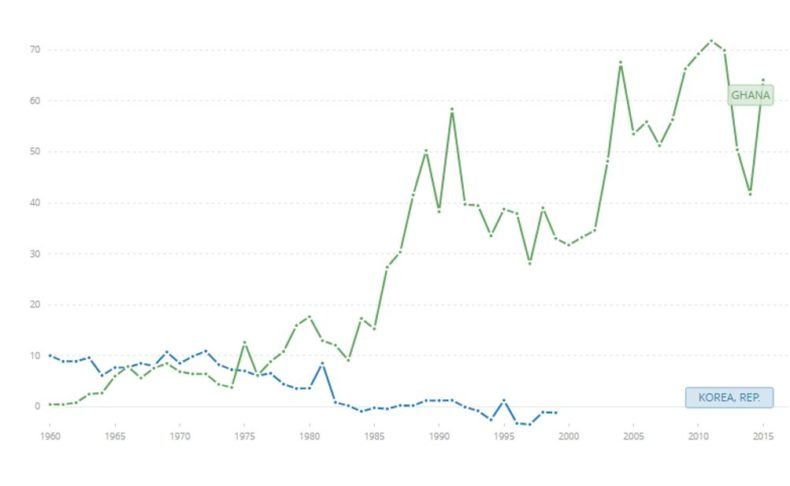

All these projects direct people’s attention to Gapminder, Human Progress, Our World in Data, and other efforts that comprehensively document how much progress is still being made today. These changes include increasing average life expectancy, cutting extreme poverty, reducing childhood mortality, increasing wealth, supplying greater access to education, and empowering women’s rights.

Yet merely pointing out the facts of progress isn’t enough to persuade a lot of folks. It would be great, says Karabell, if it worked just to tell people, “You should all just read the data and change your views.” But it usually doesn’t.

So another theme that unites these four efforts is their embrace of narrative as a way to restore cultural faith in progress. “You can’t throw facts in the face of people’s emotions, or at least you’ve got to be very careful about how you do that,” says Karabell. “You can’t tell people that they should feel better just because the data tells them they should.” Crawford agrees: “Narratives have a lot of power and they have more power than charts and graphs.”

Saloni Dattani of Works in Progress explains, “One of the reasons that we started Works in Progress was we wanted to allow people to really go deep into some area that they were interested in and make a stronger case and longer case for something that they thought could improve the world or something that they thought was a challenge.” Examples include a recent long article, “Watt lies beneath,” that details how advances in geothermal energy could provide humanity with essentially unlimited supplies of clean energy, and the short video “Gentle Density: Brooklyn” describing how Brooklyn, New York, evolved into the second-most-densely populated county in the U.S.

As another example, Zurich-based Roots of Progress Fellow Alex Telford suggests over at his Liveware newsletter on Substack that the static concepts of health and disease are barriers to progress toward perfecting precision medicine aimed at maintaining bodily homeostasis. In her co-authored Salt Lake Tribune op-ed, “We should pay farmers to save the Great Salt Lake,” Roots of Progress fellow Jennifer Morales explains how water markets can stop that body of water from drying up.

Karabell continues: “How one writes that story about the future is part and parcel of shaping that future. If you begin with ‘We’re fucked,’ it’s really hard to solve your problems because you’re basically convinced that you can’t.”

These proponents of progress do not think that they will change the world overnight. “You have to create a critical mass,” says Karabell, “and ideas take a long time to have an effect on society. But things do change, cultural attitudes do change.” Dattani describes herself as an “impatient optimist.”

“Pessimism is more arrogant than optimism,” Karabell concludes. “Optimism is simply that we know for a fact that we are capable of solving problems. Pessimism is the conviction that we are not. The future isn’t worse unless people stop trying to make it better.”

This article was published at Reason on 4/6/2024.