With the temperature in Washington, D.C. in the mid-90s, it is perhaps worthwhile to recall what life was like before the arrival of air-conditioning. Below are a few excerpts from a New Yorker essay about air conditioning penned by the great Arthur Miller in 1998:

Exactly what year it was I can no longer recall—probably 1927 or ’28—there was an extraordinarily hot September, which hung on even after school had started and we were back from our Rockaway Beach bungalow. Every window in New York was open, and on the streets venders manning little carts chopped ice and sprinkled colored sugar over mounds of it for a couple of pennies. We kids would jump onto the back steps of the slow-moving, horse-drawn ice wagons and steal a chip or two; the ice smelled vaguely of manure but cooled palm and tongue…Even through the nights, the pall of heat never broke. With a couple of other kids, I would go across 110th to the Park and walk among the hundreds of people, singles and families, who slept on the grass, next to their big alarm clocks, which set up a mild cacophony of the seconds passing, one clock’s ticks syncopating with another’s. Babies cried in the darkness, men’s deep voices murmured, and a woman let out an occasional high laugh beside the lake…Given the heat, people smelled, of course, but some smelled a lot worse than others. One cutter in my father’s shop was a horse in this respect, and my father, who normally had no sense of smell—no one understood why—claimed that he could smell this man and would address him only from a distance…There were still elevated trains then, along Second, Third, Sixth, and Ninth Avenues, and many of the cars were wooden, with windows that opened. Broadway had open trolleys with no side walls, in which you at least caught the breeze, hot though it was, so that desperate people, unable to endure their apartments, would simply pay a nickel and ride around aimlessly for a couple of hours to cool off…

Elsewhere in the essay Miller writes, a “South African gentleman once told me that New York in August was hotter than any place he knew in Africa.” That was exactly the impression I got when I visited Charlottesville in August of 2000 – my first trip to the United States in summer time. I remember saying to my friends back home in Johannesburg that I have never experienced such oppressive heat on my travels through Africa.

Air-conditioning makes our lives more comfortable, but let us not forget the importance of air conditioning for the economy. As Walter Oi writes in The Welfare Implications of Invention, temperature and humidity have a strong influence on labor productivity. For example, in machine shops, labor productivity is at its peak at 65 degrees Fahrenheit with humidity between 65 and 75 percent. Productivity is 15 percent lower at 75 degrees Fahrenheit and 28 percent lower at 86 degrees Fahrenheit. Moreover, accident rates are 30 percent higher at 77 degrees Fahrenheit than at 67 degrees Fahrenheit. In many factories, temperature and humidity also affect the product, ruining paper, threads of textiles and so on.

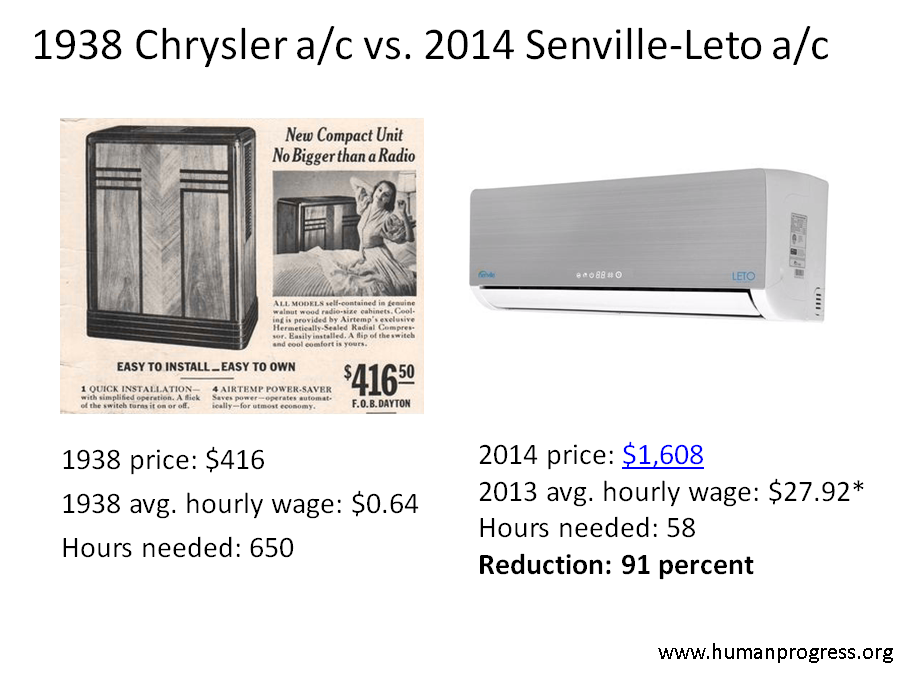

Similarly, in the old days, main-frame computers required climate control to function effectively. It was undoubtedly the introduction of air-conditioning that caused value-added per employee in manufacturing in the South to increase from 88.9 percent of the national average in 1954 to 96.3 percent of the national average in 1987. Best of all, air-conditioning is much, much cheaper and more available than it has ever been!

This post first appeared in Cato at Liberty on June 12, 2015.