Summary: This article examines how the market economy drives down the cost of automobiles over time, making them more affordable and accessible to ordinary people. It compares the nominal and time prices of the top ten most popular cars in America in 2000 and 2020, and shows that Americans had to work fewer hours to purchase a car in 2020 than in 2000. It also highlights the improved quality and features of modern cars, and argues that such improvements are largely possible through the innovation and productivity facilitated by a free-market system.

One of the greatest features of modernity is that living standards tend to gradually improve rather than remain largely stagnant – as they did for millennia before 1750 or so. Today, ordinary people have access to goods and services that the royalty of centuries past would never have thought of. Air conditioning, air travel, cell phones, personal computers, automobiles, modern hospitals, antibiotics, GPS, the list goes on. This improvement is largely due to the robust market economy that, through competition, encourages innovation rather than stagnation and complacency. As new technology arises and productivity per person increases, access to goods and services spreads, and the overall wealth of society increases.

There is much talk about U.S. economic stagnation, but, in many respects, we are better off than we were just over twenty years ago. One positive trend that’s often overlooked and underappreciated is the reduction in the length of time that blue-collar workers need to work in order to purchase a vehicle.

The falling time price of automobiles

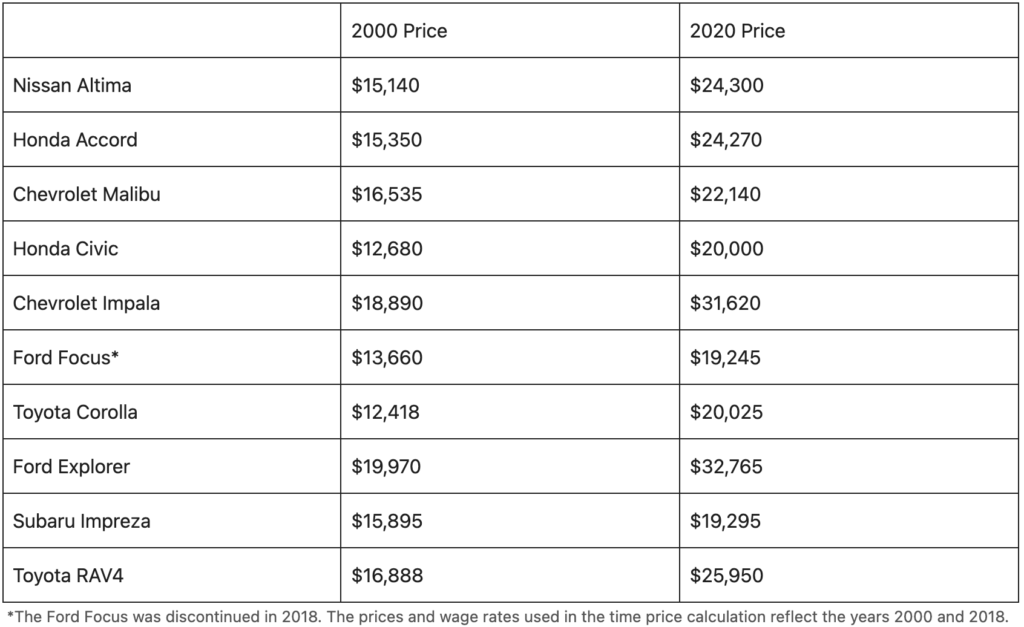

The table below contains the names of the top ten most popular cars in America in 2020 according to Insurify, a company specializing in online insurance comparisons. It also contains the nominal prices for the base models from 2000 and 2020. The prices come from Autoblog.com, a popular American automotive news and shopping website.

As you can see, the price of cars has risen over the last two decades, reflecting a multitude of factors, including inflation, better technology, and safety features. Cars are no longer simply metal boxes with engines but impressive machines packed with advanced technology.

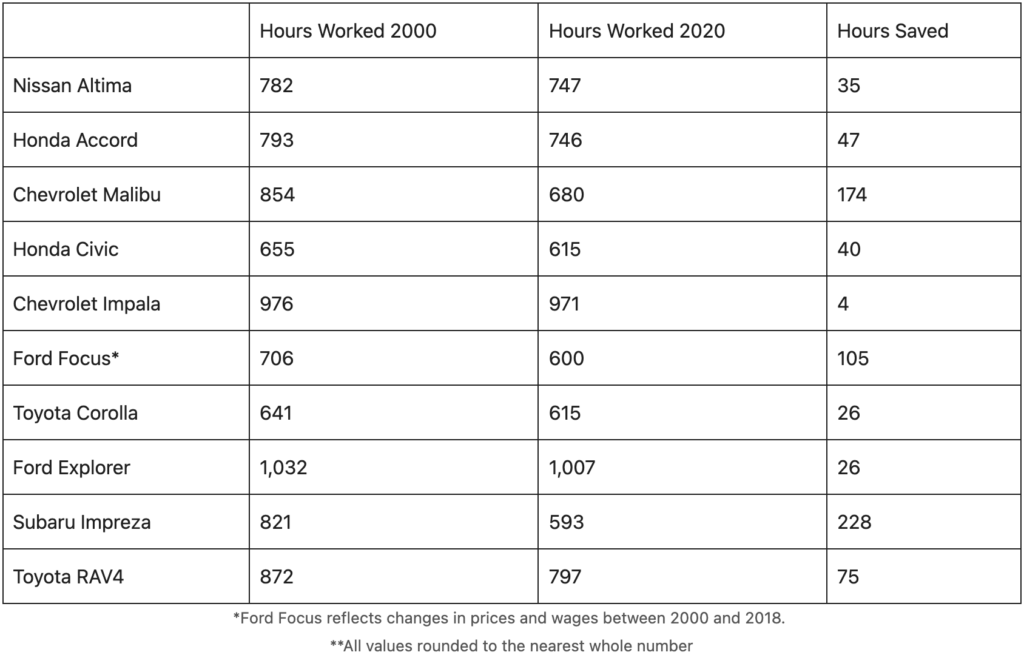

Over the same period, economic productivity, and by extension wages, have not only increased but outpaced rising car prices. According to measuringworth.com, a website of historical economic statistics, the average nominal compensation rate for manufacturing workers rose from 19.36 dollars an hour in 2000 to 32.54 dollars an hour in 2020. The table below shows the number of hours that a blue-collar worker needed to work to earn enough money to be able to afford each car in the years 2000 and 2020. These “time prices” were calculated by dividing the nominal price of the car by the nominal hourly compensation rate.

As shown by the data, Americans in 2020 had to work fewer hours to purchase a car than in 2000. Increases in productivity, which typically lead to higher wages, outpaced rising car prices. And, the cars for sale in 2020 were much higher quality than those in 2000, many of which had worse gas mileage, fewer safety features, and no air conditioning.

On average, Americans save 35 hours of work (almost a week) when purchasing a vehicle. Those working hours can now be used for other things, a perfect example of how free-market competition gradually improves living standards for all members of society.

Losing ground in some other areas

Although Americans are seeing many improvements in the quality and quantity of products relative to their wages, the trend is not universal. In the automobile industry, the incentives are arranged in a way that drives competition and innovation. However, some industries are not as exposed to market forces, often due to a combination of excessive government intervention and insulation from fluctuations in supply and demand.

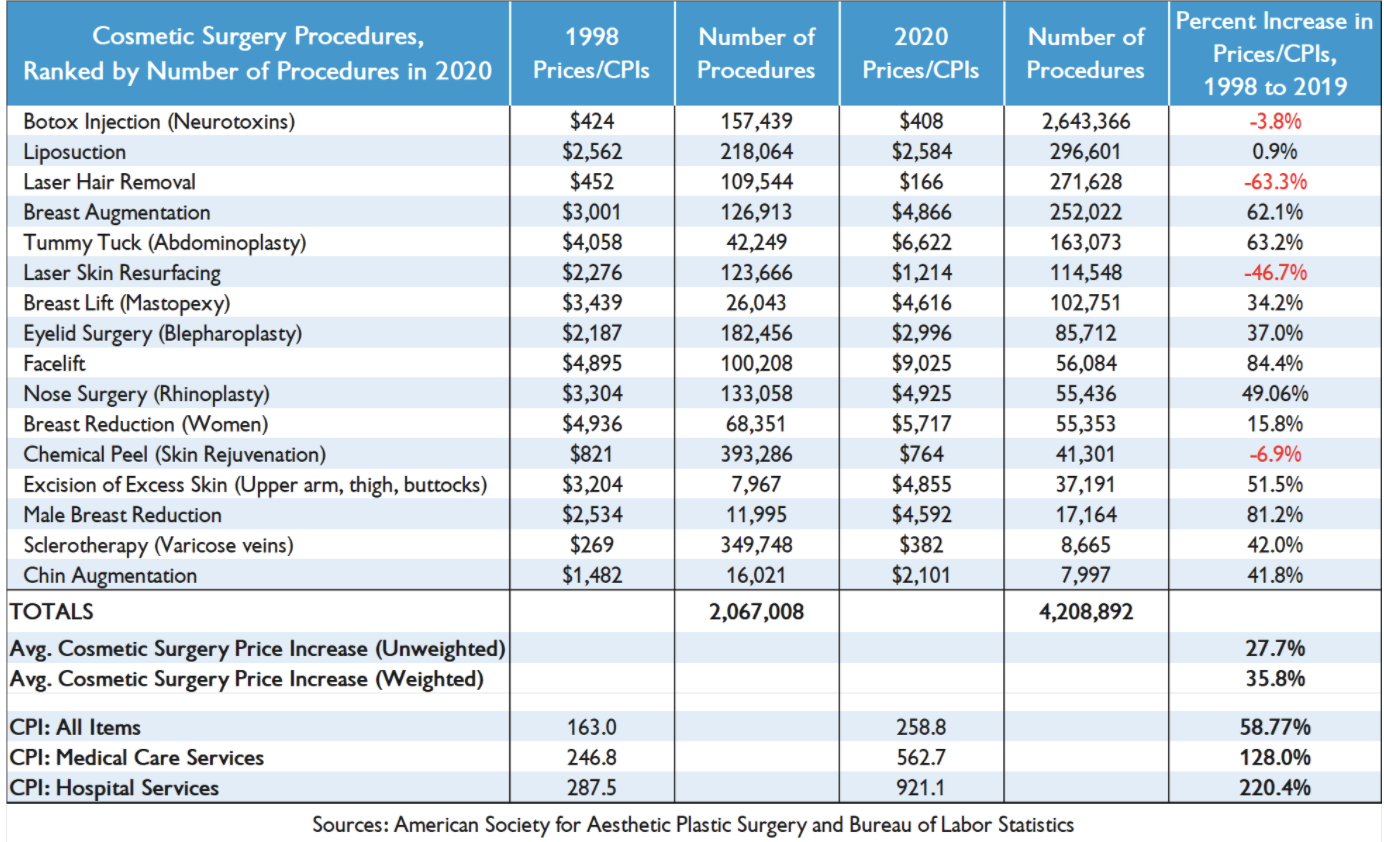

Mark J. Perry from the American Enterprise Institute, a think-tank in Washington, D.C., shows that dynamic in the healthcare sector. He notes that the cost of medical care services and hospital fees rose 128 percent and 220 percent respectively between 1998 and 2020. Meanwhile, the costs of cosmetic surgeries have increased at a far more gradual pace, with some even declining in price.

Perry argues that some of this disparity can be explained by the manner in which cosmetic surgeries, on the one hand, and medical care and hospital services, on the other hand, are paid for. He writes,

“One of the reasons that the costs of medical care services in the US have increased more than twice as much as general consumer prices since 1998 is that a large and increasing share of medical costs are paid by third parties (private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, Department of Veterans Affairs, etc.) and only a small and shrinking percentage of healthcare costs are paid out-of-pocket by consumers.”

In particular, he notes that out-of-pocket costs have gone from almost half of total healthcare costs in the 1960s to just under 11 percent in 2019. With the consumer paying only a fraction of the bill, health providers no longer have to keep prices low to stay competitive. Instead, they negotiate prices with insurance companies and the government, institutions which have a far smaller incentive to shop around for the lowest price or seek alternative solutions when faced with rising costs.

Cosmetic surgeries are financed differently–almost all costs are paid out of pocket by consumers. As such, there is a higher level of transparency as well as price sensitivity, and the services are cheaper.

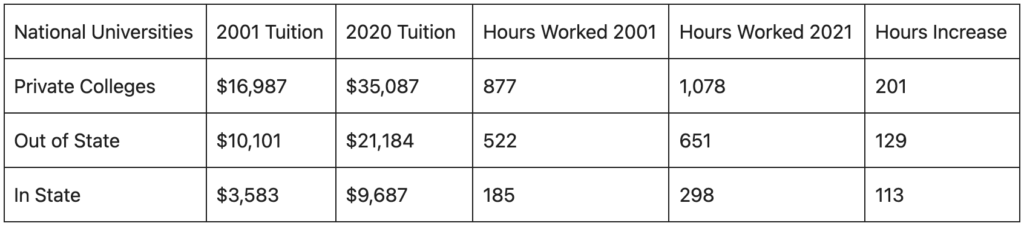

A similar dynamic exists in the U.S. higher education system, where a large share of the cost is covered by third parties, such as private loan companies, government-backed debt, and taxpayer dollars. Again, time prices (i.e., nominal tuition prices divided by nominal blue-collar hourly compensation rate) show that Americans are working far longer to afford college attendance today than in the past.

Source: US News, Human Progress.org

Some of the price increases can be attributed to universities providing additional services, such as excellent athletic facilities, better food and lodgings, etc. However, some of the price increases can also be attributed to the incentives that govern the higher education sector. Much like healthcare, a large portion of college funding comes from third parties, not consumers themselves. According to a 2016 paper published by the nonpartisan National Bureau of Economic Research,

“We measure how much changes in underlying costs, reforms to the Federal Student Loan Program (FSLP), and changes in the college earnings premium have caused tuition to increase. All these changes combined generate a 106% rise in net tuition between 1987 and 2010, which more than accounts for the 78% increase seen in the data.”

Furthermore, a 2016 paper published by Mahyar Kargar of the University of Illinois and William Mann of Emory University, which examined the effect of tightened lending standards for federal student loans, found that more restrictive policies resulted in net decreases in college tuition. That further supports the notion that the government, as a highly influential third-party lender, is largely responsible for driving up the cost of tuition because it creates artificial demand through excessive funding. Instead of being forced to compete for consumers with low out-of-pocket prices and high-quality education, university administrators face similar incentives to the healthcare providers (i.e., a large part of their revenue comes from third-party lenders such as the government, who are less sensitive to price increases). The authors conclude,

“Finally, the large average markup that we estimate suggests that a simple subsidy to consumers may not necessarily be the ideal financial aid design, and that policymakers should instead target barriers to competition in the form of large fixed costs.”

Policymakers should heed the above lessons. The market forces of competition and price sensitivity, combined with increasing productivity that leads to higher wages, allow living standards to rise. However, government policies and perverse incentives can shield service providers from market forces, undermining competition and eroding U.S. standards of living.