Summary: The long-term trend from 1919 to 2024 shows significant improvements in food abundance, with time prices for a basket of 42 food items falling dramatically. Unfortunately, the recent inflationary period has eroded a small portion of those gains.

Now that the US inflation rate seems to be heading toward the more usual 2 percent per year, it is perhaps the right time to look at the cumulative effect of the pandemic and the government’s fiscal and monetary responses to it on food prices. To provide the proper perspective on the evolution of food prices in the United States, we need to distinguish between nominal prices and time prices and long-term and short-term trends.

People often think that food prices are much higher than they really are. That’s because something can become more affordable even as its price rises. Our wages, which reflect workers’ increasing productivity, tend to grow faster than prices. So what matters is a change in price relative to a change in hourly wage, and time price (i.e., the nominal price divided by the nominal hourly wage) tells us how long we must work to earn enough money to buy something.

In our book Superabundance, Gale L. Pooley and I looked at the US food prices from the perspective of an average US blue-collar worker between 1919 and 2019. To be specific, we obtained 1919 nominal food prices from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and compared them to nominal prices as we found them on the Walmart website in 2019. We thought that a century of data would provide a good indication of rising living standards in America. We were not disappointed.

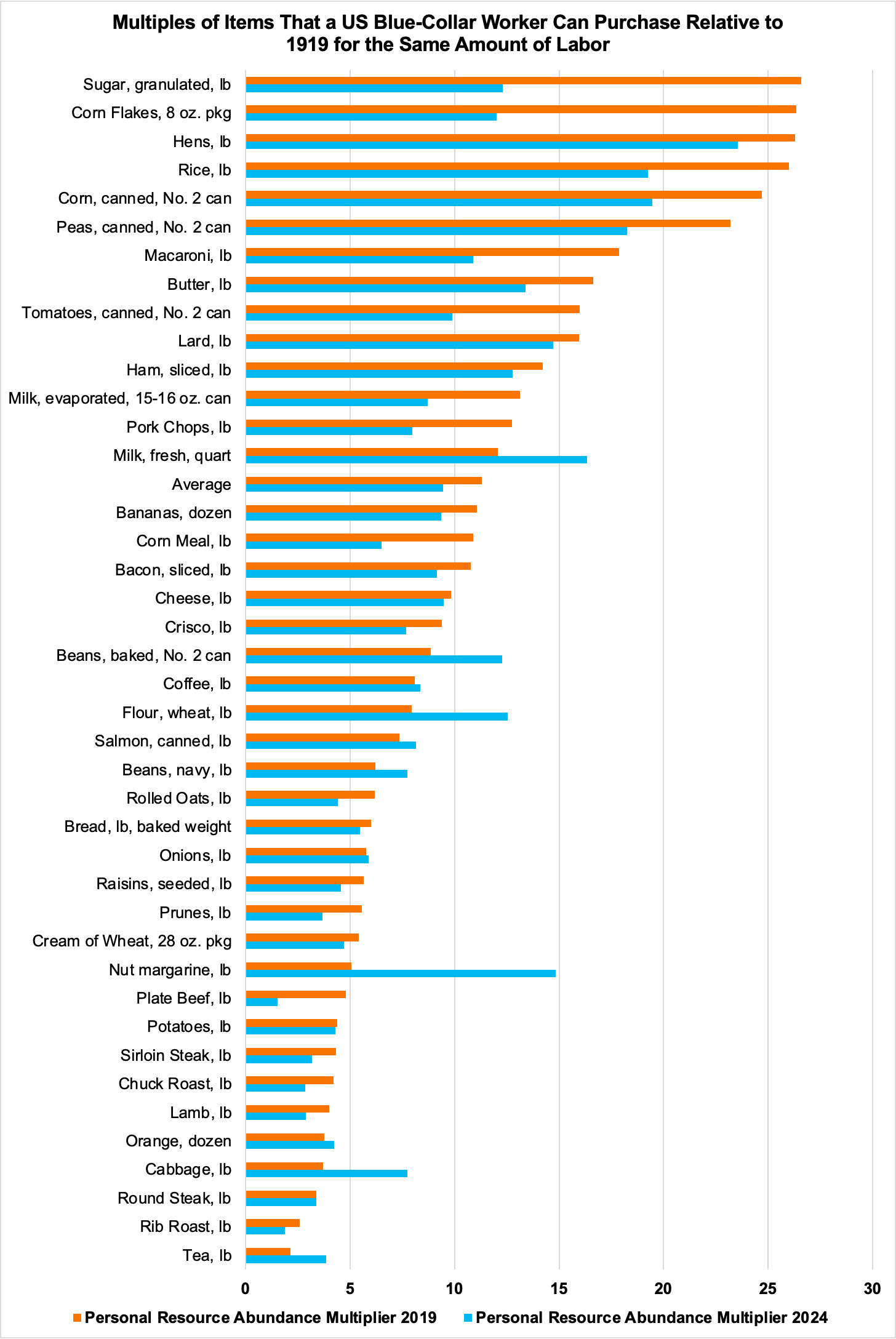

We found that that total time price of our basket of 42 food items fell from 27.26 hours of work in 1919 to 3.85 hours in 2019. For the same amount of work that allowed a blue-collar worker to purchase one basket of the 42 commodities in 1919, he or she could buy 11.73 baskets in 2019. Food abundance rose at a compound rate of 2.49 percent per year. At that rate, blue-collar workers saw their purchasing power double every 28 years.

That’s a lot of progress!

Recently, we have updated our data to 2024. This time, we compared the Bureau of Labor Statistics prices from 1919 to Walmart prices in Cincinnati—a city with the median cost of living in the United States. The good news is that the recent bout of higher-than-usual inflation (2021–2024) came nowhere close to expunging the gains made since 1919. Compared to our ancestors just over a century ago, today’s Americans enjoy a much greater abundance of food. On the downside, food is clearly less abundant than it was in 2019.

We found that the total time price of our basket of 42 food items fell from 27.26 hours of work in 1919 to 4.45 hours in 2024. For the same amount of work that allowed a blue-collar worker to purchase one basket of the 42 commodities in 1919, he or she could buy 9.45 baskets in 2024. Food abundance rose at a compound rate of 2.27 percent per year. At that rate, blue-collar workers saw their purchasing power double every 30.86 years.

In other words, because of inflation between 2019 and 2024, US blue-collar workers need to work an extra 36 minutes (3 hours 51 minutes versus 4 hours 27 minutes) to buy the same kind and quantity of foods that they bought in 2019. This 16 percent increase in time price of our basket of 42 food items is a sad reflection on the US government’s fiscal and monetary incontinence and the draconian policies implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. As ever, inflation has raised prices for those Americans who could least afford it.